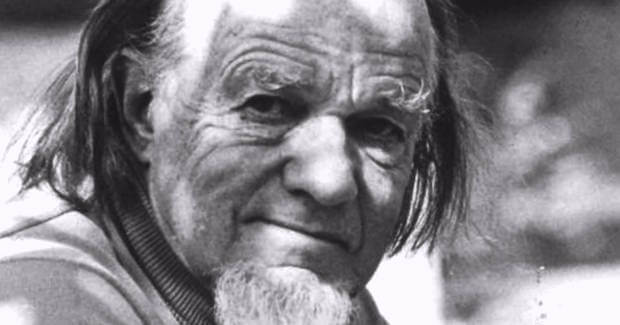

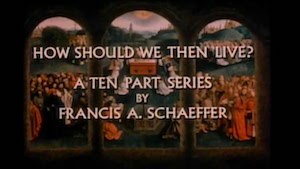

Like all freshman at my little Bible college, I took a course called Philosophy and Christian Worldview. I learned a lot from the professor, but most of what I gleaned came from watching the flickering images of a goateed man wearing knickers, projected onto a ripped screen in the college auditorium.

A version of this story could be recounted by scores of Bible college and seminary students since the late seventies. The name of the film was How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture. The man in knickers was Presbyterian pastor and apologist Francis Schaeffer.

Schaeffer died the year I was born, but like many Christians my age, his work has made an enormous impact on the way I think about the Christian faith, culture, and what it means to be a rational person.

To mark today, the great apologist’s birthday, here are four lessons Francis Schaeffer taught me about faith, doubt, art, and culture.

Art and culture are spiritually significant

In How Should We Then Live?, Schaeffer evaluates numerous pieces of art and music—from Michelangelo’s David to the bizarre, randomized compositions of avant-garde composer John Cage. Along the way, he demonstrates how the worldviews of those artists and musicians are expressed (or undermined) by their masterpieces.

Prior to encountering Schaeffer, I considered those two callings diametrically opposed. My theology was robust enough to know there was nothing unchristian about music, art, poetry, and fiction—and yet . . .

Schaeffer blew the lid off of any notion that the “spiritual” was more important than the artistic or cultural. In fact, he demonstrated that the artistic and cultural arenas could be—indeed, must be—positively Christian. The film series How Should We Then Live?—and the many other Schaeffer books I subsequently devoured—convinced me that, for better or worse, the output of culture was itself spiritual.

[Tweet “Francis Schaeffer demonstrated that art and culture could be positively Christian.”]Christians shouldn’t ignore the “secular”

By engaging with the artistic, literary, and musical output of non-christians, Schaeffer removed my fear of anything that wasn’t expressly “Christian.” When I entered Bible college, I listened solely to Christian music and looked with suspicion upon those who did otherwise. Through Schaeffer’s influence, my heart thawed. His thoughtful evaluations of art from differing worldviews gave me the vocabulary and confidence to engage with the “secular”—and to evaluate it in light of a biblical worldview.

Schaeffer’s earnest appraisals of even the most controversial writers and artists—such as Henry Miller and the aforementioned Cage—charted a course for my own interaction with music, movies, art, and literature. He demonstrated that art has power, and that, because of the fall, it should never be approached without caution. But neither should it be ignored.

Christians don’t have to fear doubt

Like many Christian college students, I began questioning many of the beliefs with which I had grown up. By the time I read books like Schaeffer’s Death in the City, The Mark of a Christian, and True Spirituality, my crisis of faith was in full swing.

The doubt that had crept into my spiritual life terrified me. I recognize now that much of what I experienced was not rational. It was what apologist Mike Licona (whose apologetic approach is markedly different from Schaeffer’s) calls emotional doubt. I sought solace in Schaeffer’s work. It helped. But not much.

Here was Schaeffer’s legacy personified. It was only by meeting my own doubts head on that I was able to overcome them. Merely knowing of the existence of a place like L’Abri gave me courage. I brought my doubts into the conversation, shared them openly with professors and peers, and studied works that addressed them. By naming my doubt, I took away its power, and made room for a vibrant faith to take its place.

[Tweet “By naming my doubt, I took away its power, and made room for a vibrant faith to take its place.”]The Christian faith is rational

There was a reason Schaeffer could confidently engage with non-Christian cultural artifacts: he possessed a strong belief in the inherent rationality of Christianity. In fact, he was convinced that Christianity provided the only rational worldview.

Part of Schaeffer’s apologetic mission was to demonstrate the irrationality inherent in non-Christian worldviews, a process he called “taking the roof off.” Picturing each person’s view of the world as a house, Schaeffer argued that Christianity provides the only reliable blueprint. Only the Christian faith can make sense of the world. By pointing out the inconsistencies of a non-christian worldview, Schaeffer took off its roof, allowing the truth of Christianity to come crashing in. Then he rebuilt the house from the ground up, based upon the true, Christian blueprint.

I had never seen this method before, and I have never seen anyone use it as effectively since. There were times in my young Christian life that I struggled with some of Christianity’s claims, but when Schaeffer took off the roofs of opposing worldviews, it seemed clear: no alternative to the Christian view was viable.

Francis Schaeffer’s apologetic approach was unabashedly rooted in his belief in the power of God’s Word.