A clever and provocative author wrote something clever and provocative recently about Bible translation:

We are accustomed to say things like “something got lost in the translation,” which it frequently does. But can anything ever be gained? Let me pose a question for you all, without attempting to answer it myself . . . .

Here is my question. Suppose you take an average Greek-speaking Christian in Asia Minor about 200 A.D., and you give him a copy of the book of Ephesians in Greek, which he reads ten times. Now take a modern Christian who knows both English and French. Give him ten different translations of the book of Ephesians, 7 in English and 3 in French. He reads each one of them once through. Who now has a better grasp of the message of Ephesians?

I merely pose the question and run away.

Well I’m slow, and as he runs away I’m stuck here holding the bag. I simply have to take up this challenge and answer this fascinating, stimulating, clever, provocative question.

10 Translations or one Greek Bible?

I am so torn here, but if a clever and provocative person were to make me cross my heart, hope to die, and choose who would know Ephesians better, I’d have to vote for the guy who reads multiple Bible translations in English and French. He will understand Ephesians, um, 23% better than the guy who just reads it in Greek.

Here’s why I vote this way: translations are the first line of Bible teaching, the first line of interpretation. And it’s a line extremely close to the baseline. Having ten translations is like having ten teachers who are focused, laser-like, on the Bible text, doing barely anything more than reading it with expression and feeling. (Have you ever gained a better understanding of the Bible just by listening to your pastor read it out loud? I have.) Their expressions and their feelings will differ for various reasons, and it is in those contrasts that the value of reading multiple translations lies.

Those contrasts occur because, while it’s easy to read your own language lazily, when you translate from one language to another, you are forced to slow down, to notice things and make choices. What’s the force of that participle? What’s the use of that genitive? Where does the sentence or paragraph break occur here? Where does the emphasis lie in this sentence? Which sense of this verb—there are two possibilities—did the author intend?

Yes, things can get lost in translation—but I believe things can be gained in translations, plural. Somewhere in the nexus of tiny interpretive decisions flying around and bumping into each other, translation to translation, understanding grows. If it didn’t, I would’ve stopped bothering to check other translations somewhere between now and 1999, when I first picked up a Bible with different Bible versions in parallel columns.

I don’t want to say that translations add something to the Bible, anymore than a pastor adds something by his teaching. But I can’t and won’t deny my experience here, however you account for it doctrinally: using multiple translations helps me understand the Bible better.

Which Bible Translation is Best?

People argue, incessantly, over which translation of the Bible is the best. After almost 20 years of using all the translations they argue about, I feel like offering these arguers a Bob-Newhart-style counseling session:

Now, arguments over Bible translations are not entirely pointless. There are significant differences between translations, or I couldn’t write a post about the value in those differences. But the “which is best” argument is the wrong one to have. By focusing on an unanswerable question—best for what, for whom, for when?—we fritter away energies much better spent on just using our good Bible translations. (Incidentally, using them is the best way to gain an informed opinion about them should a clever and provocative person ever compel you to argue about them.)

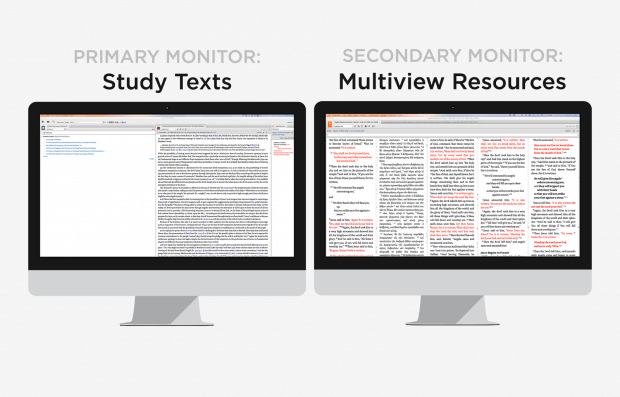

In my personal, provocative-but-not-so-clever opinion, the greatest value of Bible software is how easy it makes it to compare and contrast Bible translations in multiple languages. That’s why I’m so utterly sold on the Multiview Resources feature in Logos Now, and why I use it all day every day, dedicating an entire external monitor to it. In a glance I can compare the Bible translations I find most useful.

Take heart, you who don’t read Greek and Hebrew. Reading the original languages is incredibly valuable, but you can mimic that skill and get much of the same value by comparing Bible translations in languages you can read. Had a little Spanish? Trot out your Reina Valera. French? Louis Segond. Urdu? Well, more power to you.

You have to be really sold on the value of a text to buy and read and repeatedly use different translations of that text. For Dante’s Divine Comedy, give me what is generally regarded as the “best” translation. I’ll probably be impatient with questions like “best for what?” I just don’t care enough. But we’re talking about the Bible here. God’s words. God’s words. We are privileged to have many good translations of those words, all of which—especially when you do use them all—are helpful for knowing what they mean.

The Best Bible Translations

OLSHA members, let’s end Bible translation tribalism. The consensus of evangelical people who know Greek and Hebrew and believe in the inspiration and absolute truthfulness of Scripture is that the following translations are useful, and nothing to be afraid of (as long as you have a basic sense of which ones are more “literal” and which ones are more “interpretive”). Make sure you own and use these in Logos:

- English Standard Version

- New American Standard Bible

- New King James Version

- NET Bible (with valuable translation notes)

- Holman Christian Standard Bible

- New International Version

- New Living Translation

The cheapest way to get these translations is to buy a base package. The Starter base package has most of them.

I also use older translations like the KJV and Tyndale, because I have access through my alma mater to the (very expensive) Oxford English Dictionary and can decode archaic vocabulary as necessary (this is another post for another day). I also use Spanish, French, Italian, German, and other translations occasionally, when I’m really intent on finding out what the democracy of translators has “voted.” I will also happily check Catholic versions such as the NAB and NJB; mainline Protestant translations such as the NRSV (honorable mention: RSV) and CEB. I occasionally feel that I see Catholic or mainline bias coming through in those versions, but not often. And evangelical bias fills my bulleted list—I just happen to share that bias.

I also check the Vulgate and Septuagint frequently—and I am leaving out quite a number of other English translations that deserve honorable mention. But they won’t get it today.

An Encouragement

I don’t want to give anyone an excuse not to learn Greek or Hebrew. If you are called to any kind of Bible-teaching ministry and you have the opportunity to study these languages, you most definitely ought to.

I do, however, want to encourage people who aren’t called to that kind of ministry or haven’t had that chance to study the original languages of Scripture. I won’t make you promise anything, but I do want to provoke you to love and good works. You don’t have to be clever. Just make it a regular habit to use multiple translations of the Bible.