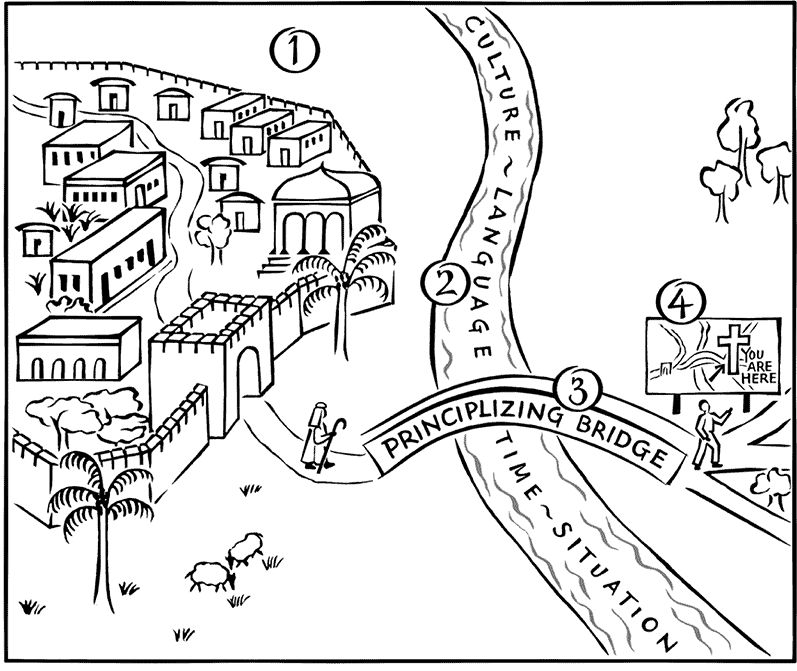

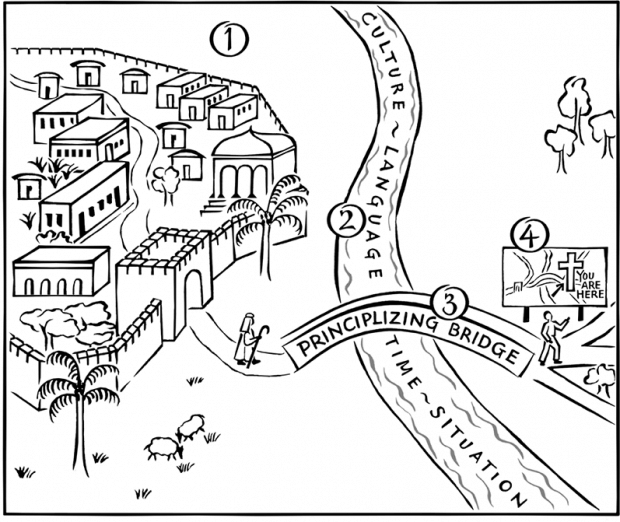

You and I live in a modern city, but imagine that across the river is another town very different from ours: an ancient one. We drive cars, they ride animals. We chat over coffee at a cafe; they chat over water at the community well. We suffer from a divisive and polarizing political situation; they—well, they do too. Not everything has changed in the last few thousand years. But our two towns are indeed separated by a river of differences in culture, language, and history.

Image courtesy Zondervan.

Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hays tell a version of this story in their popular textbook on biblical hermeneutics, Grasping God’s Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible. They use it as an illustration to help Christians go beyond merely reading the Bible to studying it.

And that’s what we’re doing with Psalm 44 in this series on Observation, Interpretation, and Application. This week: Interpretation.

In order to cross the bridge and come back with gold for our own spiritual lives, Duvall and Hays suggest we use the following four steps (a final step, grasping the text in our town, will be saved for our final post in the series):

1. Grasp the text in their town

Our first job is to seek God’s intended meaning in the original historical-cultural situation. What did the author of Psalm 44 mean when, as it were, he spoke in and to his own “town”?

The nation of Israel at the time of this psalm was perplexed and near despair. Was their intense suffering a sign God had rejected them? Psalm 44 puts words to the nation’s spiritual distress. The author clearly trusted and honored the Lord: the first eight verses prove that. But he could not understand why the Lord had disgraced the Israelites and abandoned them to their enemies. “This isn’t divine judgment for our sins; so what is it?” He never directly challenges God with wrongdoing; he only asks why—“Why are you sleeping?,” “Why do you hide your face?” And he ends the psalm with an appeal to God’s steadfast love. This is a believer saying “I believe! Help my unbelief!”

Psalm 44 doesn’t just express the nation’s feelings of frustration; it expresses their faith. They still instinctively reached out to Yahweh and not to other gods. They recognized that it was for his sake that they were “killed all the day long” (v.22). And they appealed to him as their covenant Lord in the final line: “Redeem us for the sake of your steadfast love!” This is not something worshipers of Baal could pray; only the Jews could. They could appeal to statements in their law such as this one: “the Lord set his love on you and chose you . . . because the Lord loves you and is keeping the oath that he swore to your fathers” (Deut 7:7-8). Psalm 44 is just such an appeal.

“Steadfast love”—as a Bible Word Study on the Hebrew term here, chesed, will show you—is the loyal love of covenant faithfulness. (Except perhaps in Esther 2:9.) The psalmist is appealing to the covenant God made with Israel.

2. Measure the width of the river

The most significant difference between the two towns—the widest point in the river separating them—is not technological or linguistic. It’s covenantal. It’s B.C. and A.D. One stands before Jesus, the centerpoint of history, the other after him—and after the institution of his “New Covenant.”

Christians believe different things about the level of continuity between the Mosaic covenant and the New covenant, but we all agree that the two covenants are not the same. There are elements of the old covenant, the Mosaic, to which Psalm 44 appeals; and there is, therefore, a certain distance between us and the psalm.

No other nation on earth can say to the Lord what the psalmist does in his opening lines. It’s Israel whom God planted in the land, Israel in whom God delighted. When American, Turkish, Chinese, or Djiboutian Christians read this psalm, we must be clear in our minds that God never promised to go out with our respective armies, nor to plant us in our respective lands. Political leaders of any nation are always wont to claim divine sanction for their actions (even secular leaders claim to be on “the right side of history,” as if the future itself is a transcendent source of norms).

Although it’s possible for Americans or Kazaks or Djiboutians to responsibly use this psalm in a time of national turmoil, certain phrases won’t directly apply. We can’t refer to ourselves while praying to God as “your people” (v.12). Most importantly—and this is particularly crucial for American Christians, who have often viewed themselves as the new Israel—we cannot appeal to God’s “steadfast love” (v.26), his covenant faithfulness, to our nation. No doubt God has shed his grace on us, from sea to shining sea, but there’s an ocean of difference between God’s explicit national promises to Israel and his international promises to the church. It is a dangerous compromise with American civil religion to commandeer God’s promises to Israel and keep them for ourselves.

I beg your indulgence for my moment on the soapbox here; my major point is not about America in particular but about differences between the two major covenants of the Bible in particular. We must keep them as distinct as the Bible does.

3. Cross the bridge

If the river is so wide, why bother making the arduous trek across the bridge at all? Because the character of God is still evident in Psalm 44, and that character does not change even if God’s steadfast love is manifested differently today in our town than it was in theirs. Psalm 44 is a way for the divine author to acknowledge that it’s not always possible for his people to see his purposes behind their pain; it’s divine permission for believers to ask why the Lord appears to be asleep. And the rest of the Bible shows that this is a message, a principle, that is still fully valid.

Think about the dynamics here: God inspired an ancient Israelite to levy hard questions at his Lord. What does this imply? That it’s not inherently wrong to ask God, “Why?!” It need not (though I think it can; it depends on your heart motives) be faithless and blaspheming to ask God why it looks like he’s asleep. We Christians don’t have the same covenant with God that Israel did; we have a better one, enacted on better promises (Heb 8:6–7)! The basic (and literarily artful) structure of the psalmist’s argument is one we can still use; when we’re undergoing trials we can appeal to God’s steadfast love—his covenant faithfulness in the New Covenant.

4. Consult the biblical map

You could come up with erroneous “principles” from Psalm 44, such as, “When I don’t like my circumstances it’s because God is being faithless to his covenant with me,” or “God sometimes punishes people for being good.” These errors would be major stretches even if all you knew of the Bible was Psalm 44. But the Bible is a lot bigger than this one medium-sized psalm. You’ve got to keep it all in mind.

Consult the biblical map: evaluate whether or not the principles you derived from this psalm really fit with the rest of Scripture. Is it true elsewhere in the Bible that it’s not inherently wrong to ask God, “Why?!” Sure it is: there are plenty of other laments in the psalms. Job also comes to mind. So does Paul and his thorn in the flesh. In these places in Scripture people suffer in ways they don’t understand and appeal to God to change their circumstances. Sometimes, as with Job, God alleviates the negative circumstances. Other times, as with Paul, God explains that he has something to teach through the pain, and Paul accepts this (2 Cor. 12:7). In the case of this psalm, God gives no final answer.

Conclusion

“Observation” and “Interpretation” are not fully distinct. You can’t help interpreting as you observe. You made something of the Psalm 44’s abrupt shift from praise to lament; you couldn’t help it.

But the turn from observation to interpretation is a self-conscious move from questions of substance into questions about meaning. What did the psalmist intend for his readers to do with this psalm? And what did God intend for today’s readers to do with it?

And that means that interpretation itself is not fully distinct from application. As theologian John Frame has pointed out, if you don’t know how to use a given passage of Scripture for God-glorifying ends, you don’t really understand it.

Nonetheless, it’s helpful to distinguish their town (observation), our town (application), and the bridge in between (interpretation).

Next week, we bring the truths of Psalm 44 fully into our town by applying its principles to parallel contemporary situations.