Learning New Testament Greek is a fantastic idea—and perhaps an intimidating one. I don’t want to add to the difficulty.

And I also kind of do.

I have a suggestion that will help you in the long run: try learning about language more generally before learning Koine Greek in particular.

4 biblical language principles

These four simple biblical language principles will improve your Bible study regardless of whether you ever take the many, many hours necessary to gain proficiency in New Testament Greek. (If you do end up studying Greek, sound biblical language principles will guide and shape your study by attuning your questions and focusing your answers.)

1. Usage determines meaning.

You’ve been accessing meaning through usage ever since you were a tiny baby. Your mom kept calling that white liquid “milk” until it dawned on you to make the same sounds (M-I-L-K) to refer to, and no doubt request, said substance.

Even a small child can learn to communicate complex ideas that are not tangible objects or substances, such as “He always gets to ride in the front!” What is an “always”? How does a tiny kid, who can’t even put on velcro shoes, come to understand and then employ such a concept? Usage determines meaning—observing others’ usage gave him access to “always.” That kid is made in the image of a God who uses language.

“Meaning” refers to intention. “What did she mean?” and “What did she intend?” are basically synonymous, along with “What was her purpose?” and even “What did she desire?” And Christian theology teaches that though human intentions and desires are real, God’s are ultimate (Gen 50:20). Ultimately God “determines” meaning.

But when you ask, “How do I access the meaning of a given word in a given sentence?” the answer can only be usage, because God hasn’t given us a dictionary. Like the child in the example above, you watch how that given word (or phrase or punctuation mark or any other feature of written or spoken language) gets used, and by doing so, you find out what people mean by it.

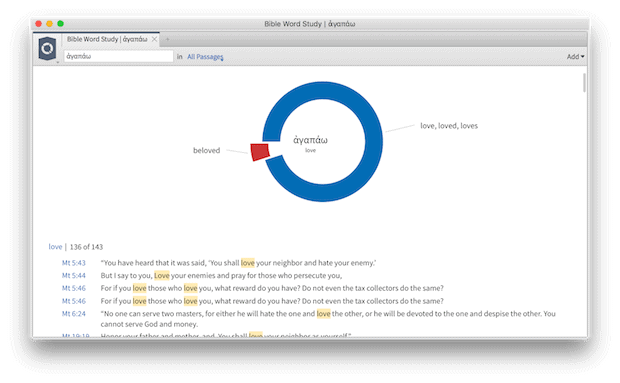

Applied to Bible study, this means that you should look at how a word is used before you draw firm conclusions about its meaning. Using the Bible Word Study tool in Logos, you have access to basically the same data the dictionary writers do (they also have access to Greek outside the New Testament, but the latter is still their most important source). I’ve used other apps, but none gives me such quick and elegant access to a word’s usage.

(If you’re wondering what Logos is, go HERE.)

In my experience, people who can’t and don’t do this kind of work tend to fall prey to linguistic errors and, not infrequently, some theological silliness. They haven’t trained themselves to recognize when “in the Greek, this word really means . . .” is just a cover for someone to insert his or her pet theology peeve. (One common example is “agape” love.)

2. Usage determines meaning—no, I mean it.

My second simple principle is a direct restatement of the first because I have discovered that I simply can’t repeat this linguistics/Bible study principle often enough. I cross sea and land to make two proselytes for it, and next thing I know they’re back into denying or ignoring it in their sermons.

There’s no way to learn language without understanding on an intuitive level that usage determines meaning. But (1) many Bible interpreters toss it out the window at the first provocation (or temptation!) and (2) many others cannot be brought to agree with it when it is presented to them explicitly.

The latter immediately sniff postmodern relativism, an attempt to undermine not just the Bible but the existence of truth itself. They don’t like finding out that, as the editor of the American Heritage Dictionary put it, “the inmates are running the asylum.” Arika Okrent, author of the fascinating book In the Land of Invented Languages, put it this way:

Our languages have inconsistencies and irregularities because they are run by us, and not by some perfect rule book or grand philosophy. (260)

It is, honestly, like a bunch of professional cyclists looking at their racing bikes and saying, “Those things could never stay balanced with a person on top of them; they would fall right over.” People will tell me with a straight face, using words that are all the results of linguistic change, that words can’t change. Unless word meaning is 100% stable, they think, meaning is 100% up for grabs. If you “let” people change their language, if you source meaning in the intentions of people, then pretty soon every teenager will do what is right in his or her own eyes and we’ll be reduced to grunting at one another. It’s a moral imperative: we must all hang with the dictionary, or the dictionary will hang us all—along with our entire way of life. THE CHILDREN! THINK OF THE CHILDREN!

And when I ask such people, “How does the dictionary know what a word means?” (the answer is usage), they seem utterly bamboozled. This is a problem.

To be sure, I have very little idea how bridges hold up cars; I have no idea how ibuprofen relieves headaches; and Joe Q. Citizen should, in my opinion, be left free to live and die without ever reading a word about linguistics. He can be a faithful Christian while living in total ignorance of the field.

But you, I presume, are either a Bible teacher or someone who wants the instincts of a Bible teacher. That’s why you’re interested in learning Greek. And you, I say, will benefit greatly from the insights provided by the study of biblical language principles.

Here are the places to start, from a bit simpler to more advanced:

God, Language, and Scripture by Moisés Silva, part of Foundations of Contemporary Interpretation.

Introductory, a modern classic: Exegetical Fallacies, by D. A. Carson.

More advanced, but short: Biblical Words and Their Meaning, by Moisés Silva.

Linguistics & Biblical Exegesis, part of the Lexham Methods Series, by Wendy Widder, Jeremy Thompson, and others.

More advanced, and long: The Hermeneutical Spiral, by Grant Osborne

(Secular linguist John McWhorter is another helpful and entertaining guide to the field. I recommend Words on the Move.)

3. Look at every level of meaning, not just the word level.

Bible readers who fail to think of the bigger picture tend to invest individual words with too much theological freight. But you don’t read books by counting words or fixating on them to the exclusion of context. I recently heard someone preach a whole sermon on the Hebrew word selah, an obscure term found in the Psalms (maybe a musical notation?), whose meaning no one knows for sure.

Bible readers who forget to think of the words, however, get lost in abstractions and end up denying what those words quite clearly say, busy as they are elucidating redemptive trajectories and all that.

That’s why we must look at every contextual level of meaning, from word to sentence to paragraph to section to book to testament to the story of Scripture. And back again.

Readers who purposefully move their focus from word to story and back, from forest to trees to forest to forest to trees to trees to forest, they shall mount up with wings as readers, they shall learn and not faint. They will, with the light of the Spirit and the grace of God, understand what the Bible is saying.

(For a brief, constructive example looking at only two of the levels, check out my post on Psalm 37:8.)

4. Learn linguistic and literary labels.

The Bible is a literary book. It contains multiple literary genres such as poetry, history, and epistle. It contains multiple literary devices such as personification, assonance, and zeugma. These sorts of tools are part and parcel (metaphor alert!) of every book worth reading, and the Bible is no exception.

If you know and understand the labels for the various genres and literary devices in the Bible, you’ll perceive what you only half-perceived before. You’ll be able to explain it more effectively to others.

Example: if you know that metaphors have a “target” and a “source” (others call these the “figure and ground” or the “tenor and vehicle”), you’ll be able to spot and understand metaphors more effectively. The source in a metaphor is the domain from which meaning is drawn to illuminate the target.

“Cast not your pearls before swine” is a rich combination of two metaphors (the Figurative Language dataset in Logos agrees). The “pearls” and the “swine” are both sources. We know how valuable pearls are and how dirty and base pigs are (or are considered to be!). “Pearls” here represent truth Jesus’ disciples possess (target)—perhaps particularly their words of rebuke for others who have specks in their eyes. “Swine” represent foolish people who don’t listen (target).

Jesus isn’t perfectly clear with either metaphor, and combining two unclear metaphors leaves open a number of interpretive impossibilities. I think Christ did this on purpose (duh) to provoke healthy thought. Jonathan Pennington says precisely the same thing about this passage in his much-praised recent book, The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing. I like this:

This is the beautiful nature of poetic and proverbial sayings: they invite many applications. (260–261)

You get this insight when you have clarity about what metaphor is and what it’s trying to do. You want to get to the place where you spot metaphors instantly and easily discern the source and target. The same goes for all the other literary genres and devices in Scripture: when you know how they work, you know how to use them.

Conclusion

It is a false choice to say, “Either learn Greek, or learn language more generally.” Gladly, you may be able to do both—and you should if you can. I’ve heard preachers who “know” Greek but don’t know language; their Greek helped them, surely, but learning a little linguistics would have helped them more.

***

Related articles

- Biblical Literacy: What It Is and How to Reverse the Decline

- The Key to Not Being a Bad Bible Reader

- 6 Resources to Help You Learn Biblical Greek and Hebrew

- 5 Reasons Learning Biblical Greek Is Worth the Pain