Logos is my preferred tool for sermon preparation, but history proves you don’t have to use Logos in order to teach the Bible carefully and effectively. Somehow Paul managed pretty well without it. Augustine and Chrysostom reportedly didn’t use it either. Calvin, Luther, Edwards, Spurgeon, Bavinck, Lloyd-Jones, Frame—pick your heroes (I’m writing this, so I get to pick mine). I for one am thrilled if you live and preach the Bible, whether you use Logos to do it or not.

I’m confident that I preach and teach more effectively because I have Logos, but let me make something clear: I’m not saying digital is better than paper or even that Augustine would have done better exegesis if he’d had Logos. Chesterton had it right:

If I set the sun beside the moon,

And if I set the land beside the sea,

And if I set the town beside the country,

And if I set the man beside the woman,

I suppose some fool would talk about one being better.

This is all true. Digital isn’t “better” than paper.

However. I must point out that the sun is better than the moon when I need to power my solar panels. The land is better than the sea when I want to plant corn. The town is better than the country when I need to find a gas station. And men are better than women—uh, maybe I should stop here . . . No, got one: when I need low basses for an all-men’s choir.

If I set digital beside paper, it would be foolish to say one is “better” than the other, full stop. They’re both great tools. I use both.

But, for me, digital is better when I need to prepare a sermon. That’s why I use Logos.

It has everything I need.

1. I need a flexible English Bible

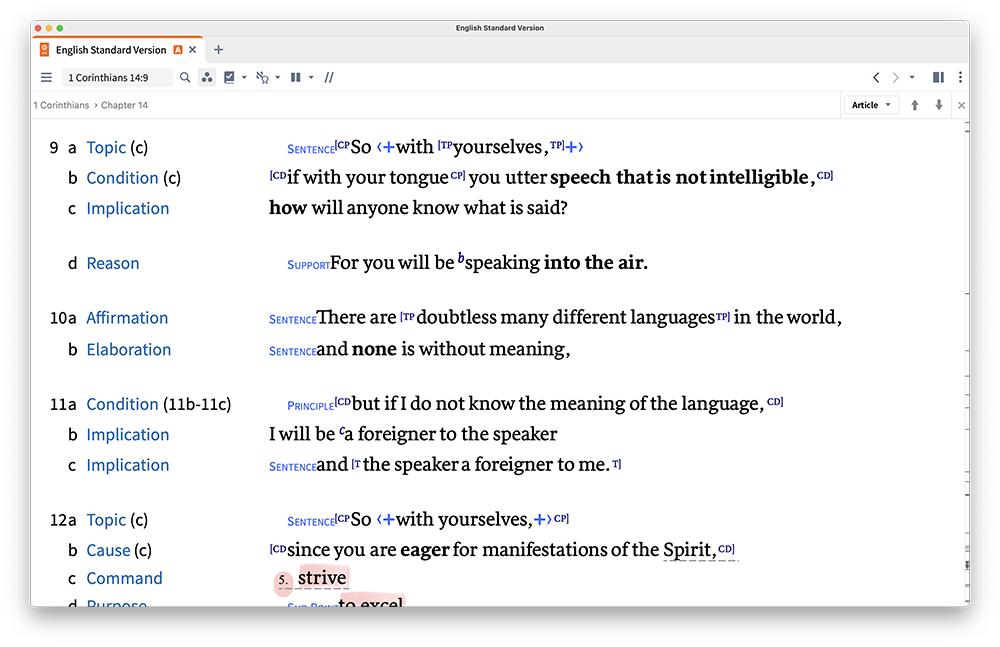

My most basic, foundational sermon prep need is easy access to the relevant Bible passage(s) in English. Logos is the best way for me to meet this need because I like to take in the whole passage at once, and I can do so best with the visual filters in Logos. They strip out all extraneous information and let me focus.

And whenever I want, I can add in a bunch of analysis tools:

Paper Bibles simply don’t offer this kind of flexibility.

2. I need to check multiple Bibles

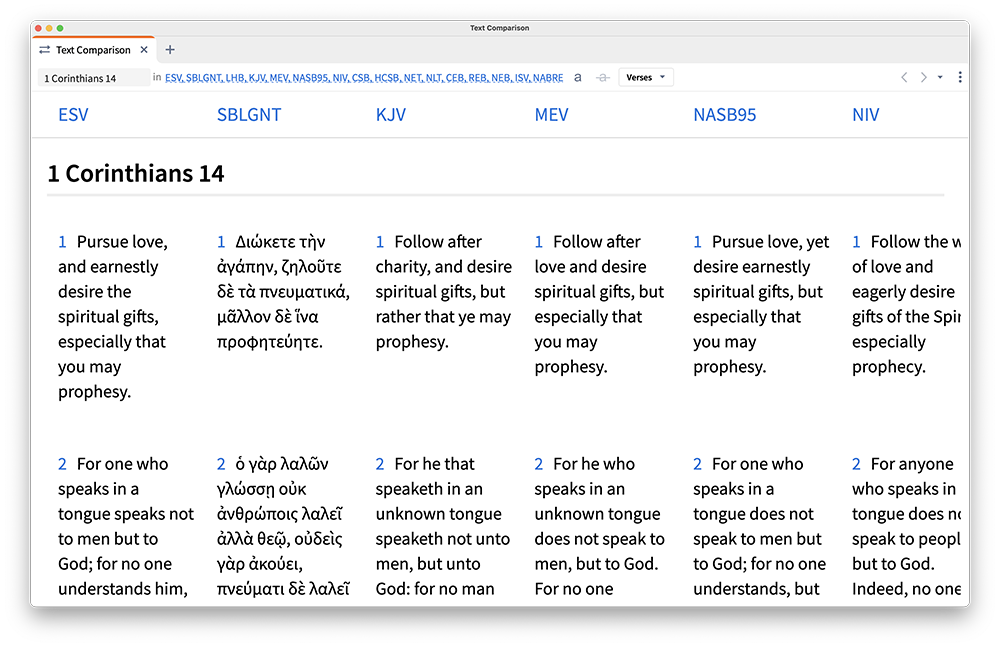

When I prepare a sermon I also need to gather quick insight from multiple English translations. I used to use a paper Bible for this task, but I could never find an edition that gathered the translations most relevant to me—and I was stuck with four, no more. I commonly check the SBLGNT, ESV, AV, NASB95, NIV, NET, HCSB, and NLT. And Logos is the best way to do this.

I asked, and my local Christian bookstore doesn’t have any SBLGNT-ESV-AV-NASB95-NIV-NET-HCSB-NLT comparative study Bibles in stock. The nice lady was very apologetic, and no she couldn’t order any either and could I please not call again?

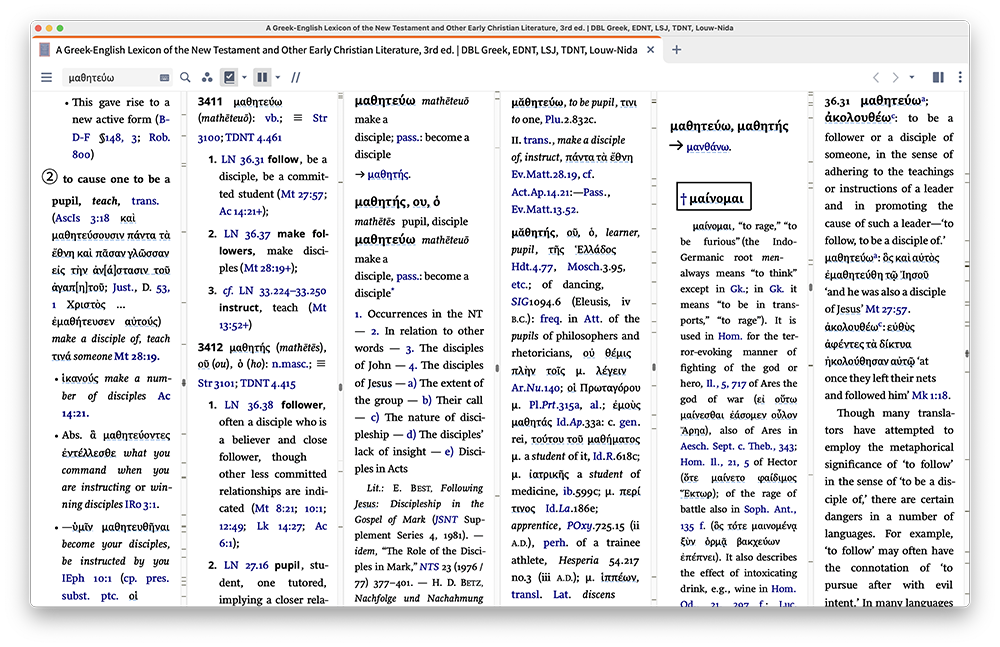

3. I need to look up Greek and Hebrew words quickly in multiple lexicons.

I rarely mention Greek or Hebrew in sermons, just like a chef doesn’t tell diners the ingredients of all his dishes—but I just as rarely fail to take a look at the original languages while preparing messages. Regularly, of course, I need to look up words in appropriate lexicons. Here, too, I like to check a variety of Greek and a variety of Hebrew resources. BDAG and Louw-Nida offer different angles on Greek words; HALOT and BDB offer usefully different viewpoints on Hebrew ones.

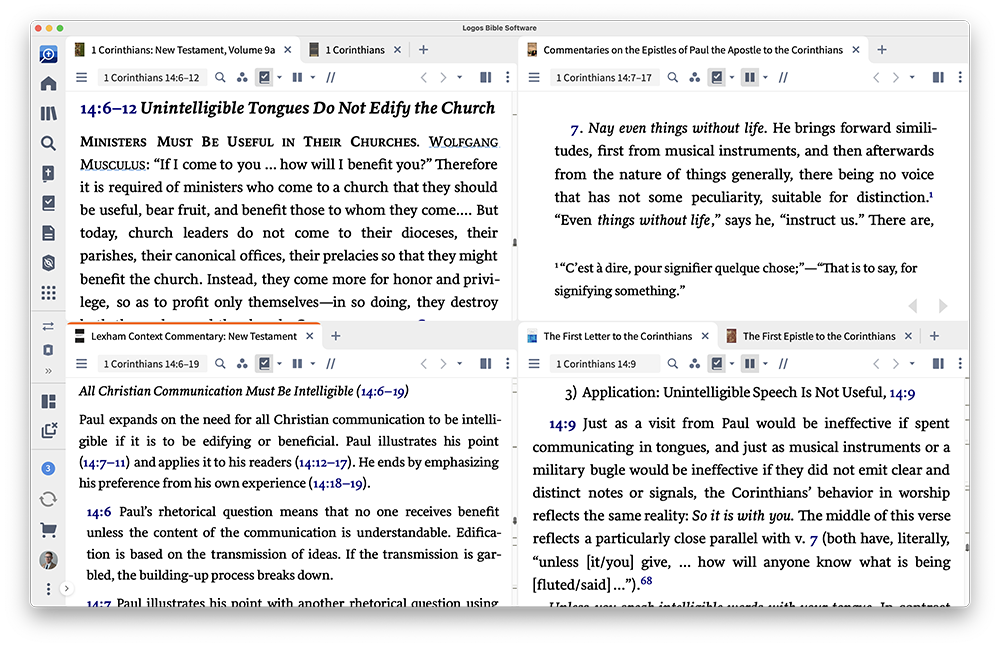

In my paper-writing days, I almost never checked multiple lexicons; it was just too much trouble. But my computer can flip pages so much more quickly than I can. With Lemma in Passage, I can access BDAG with a single click while I read the English Bible. And with Multiview Resources, I can see multiple lexicons in parallel.

Humans write dictionaries. They’re not perfect. When it comes to lexicography, two or three heads are better than one.

4. I need to study Greek and Hebrew words.

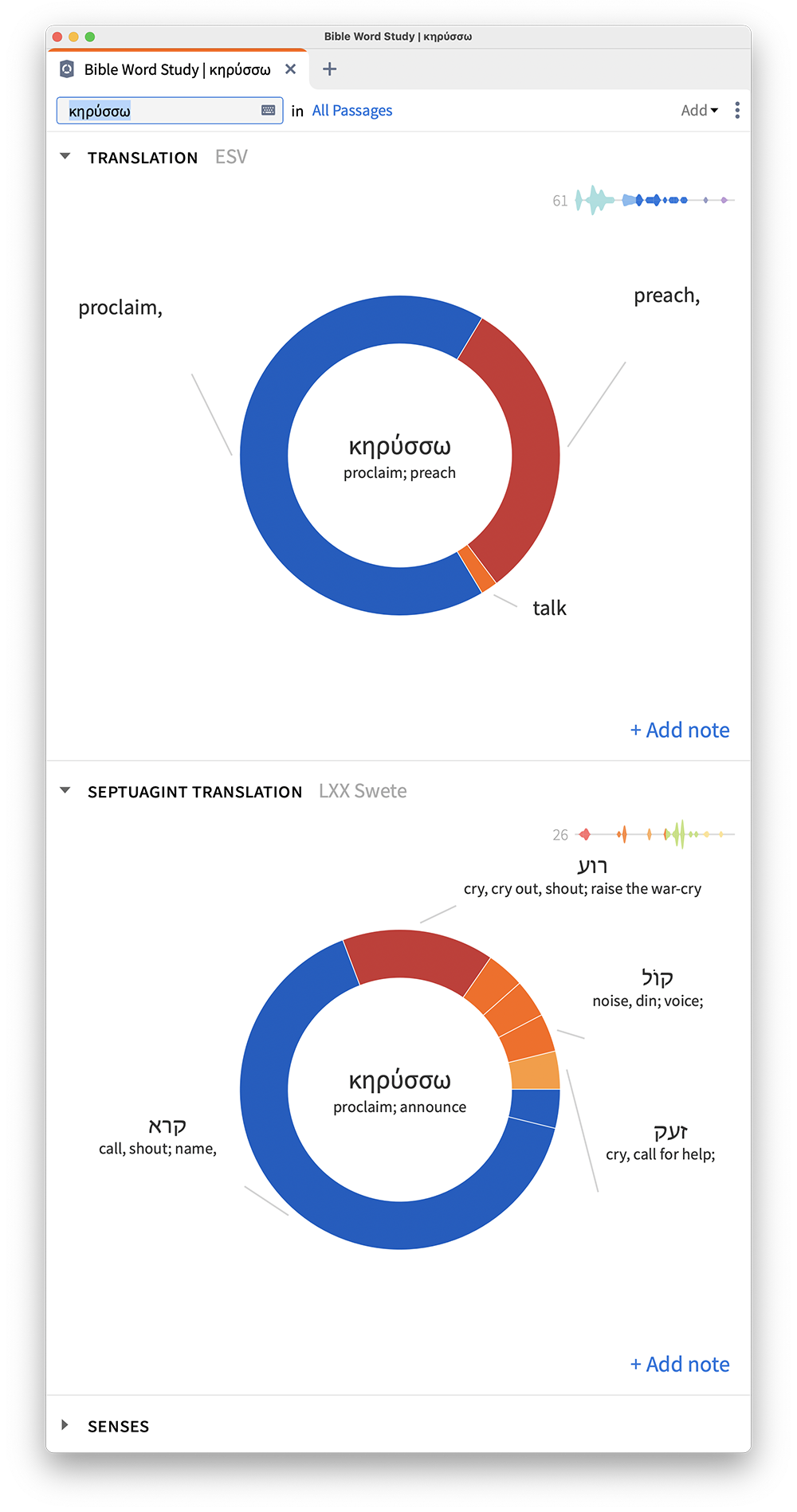

I try by God’s grace to maintain a holy fear of standing in front of Christ’s people and preaching something, anything, that isn’t true. So when the interpretation of a given passage really hinges on the meaning of a particular word (ἀρσενοκοίτης, προγνώσις), I want to see for myself how the biblical authors used that word; I don’t want to have to preach, “Thus saith Bauer.”

Before Logos’ Bible Word Study, I looked up a word’s uses, I checked the LXX and maybe the Vulgate, and that was it. It was impractical to do more unless I was truly desperate for information and had lots of time. If someone had suggested to me, “Why don’t you build a beautiful graph showing the different ways the ESV translates this Greek word—and another one for which Hebrew words the LXX uses this word to translate?,” I would have hit that person, nicely, with my copy of BDAG.

But all these things are what the Bible Word Study does for me—plus more. It not only gathers all of the information I used to gather for word studies, it also grabs all the stuff I would have grabbed if it had been feasible. It tells me who in the Bible is the subject or object of a given verb. It gives me related words. Josephus and the Apostolic Fathers get pulled into the party. And boy are they a riot.

5. I need to examine commentaries.

I remember the first time I picked up a commentary in my university library. I had used a study Bible before, but I really had no idea what a commentary was—except that it was a “requirement,” for class. I picked up J. N. D. Kelly on Acts, as I recall, and got nothing out of it. I hadn’t looked closely enough at the text to figure out what questions I should be asking, and I lacked the skill to come up with most of those questions.

Bible study is a set of hermeneutical “virtues,” a group of practices aimed at the goals of understanding and love (1 Tim 1:5). At some point after being exposed to the practice for several years, I began to see more value in commentaries. Now they are my trusted (though occasionally exasperating) friends. They do for me things I don’t have the time or expertise to do, looking up obscure information I wouldn’t know or think to look up and canvassing the voluminous discussion on a given passage. They talk through the logic of it.

And the more good commentaries I have, the better—to a point. That point, for me, is usually between three and six volumes. Logos will open all of your favorites to the right page instantly, which simply means that you can check more of them in the sermon prep time you have.

6. I need to find and use relevant articles, books, and reference works.

A pastoral mentor of mine was once accused of making up a real-life illustration because it was so apropos, so impossibly perfect for the passage he was preaching. Reality was that he had read the illustration in a book years earlier and diligently saved it in his notes on that passage. Otherwise, finding that illustration would have been like the proverbial needle in the proverbial haystack.

But computers are such neat needle-organizers that, actually, needles have been making it into more and more sermons around the world since Logos achieved widespread use. Logos can find your Scripture reference in any of a thousand—ten thousand—resources in your library. Journal articles, encyclopedias, dictionaries, maybe the IVP Essential Reference Collection.

Illustration is still an art; Logos doesn’t write my sermon for me. But it gives me access to valuable resources I would never find otherwise.

7. I need to jot down my findings and build an outline.

I need to write things down or I won’t remember them (unless they’re useless facts I wish I didn’t remember, like the name of the actor who played MacGyver in the 1980s—Richard Dean Anderson). It has never worked for me to enter the pulpit without notes. I’ll forget what I studied so carefully.

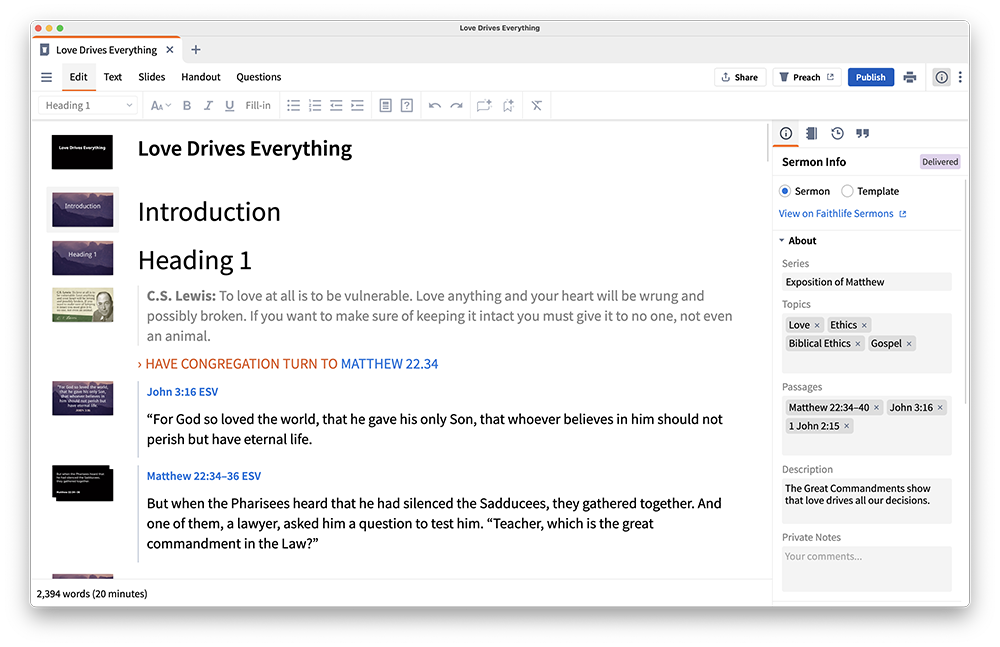

If you haven’t heard, Logos includes a Sermon Builder in the app which lets you jot down your observations, create slides, and build an outline. I need this. I can’t write long documents with a pen anymore. Future archaeologists will find a stash of Uniball Micros in the ruins of my home that were purchased in the late 1990s and then never used to their full potential.

As I gather relevant quotations from Logos, I can toss them into my growing sermon document, where they will automatically link back to where they came from (so I don’t forget where I got the quotes and get nailed for inadvertent plagiarism), and where they will automatically become slides in my visual presentation.

8. I need to produce a visual presentation.

Did you catch that? They will automatically become slides. I need this.

Sermon Builder automatically turns verses and outline points into slides.

I may be wrong, but I think digital tools are better at creating visual presentations automatically from my sermon notes than paper ones are.

Conclusion

Augustine, Calvin, and Edwards may not have used Logos, but the fact is that several theologians and exegetes whose work I appreciate do use it. John Piper practically gushes about Logos in a recent post, and he does it not as a paid shill but as a lover of the Bible and of good books about the Bible.

I have been reading on my iPad in Logos, and the main reason is because of how easy it is to highlight or to do clipping so that what I just saw will immediately go into a document. I can print out that document. Oh, I can remember in years gone by how many hours and hours and hours and days and days I would spend underlining books and then going back and typing and typing and typing to try to save what I had seen for use in books and so on. And now, oh God be praised, I could just read, highlight—bang!—they’re in a document. These wonderful insights of these great, historic lovers of God have been preserved and now I can read them later. I can use them later.

This is exactly my experience—another reason why, for me and (most of) my purposes as a preacher and Bible student, digital is better than paper.

I won’t spiritualize the purchase and use of a product. I’m making a pragmatic argument: for me, digital is better than paper when I want to prepare a sermon.

***