We may hate to admit it, but if we’re honest with ourselves, even our favorite English Bible translations can at times be clunky. Here’s an example I was just teaching about in adult Sunday School. Check out the three phrases I bolded: “your work of faith and labor of love and steadfastness of hope in our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Thess. 1:3).

“Labor of love” sounds natural enough—but only because it’s a stock phrase in contemporary English, borrowed straight from the KJV. The other two phrases, however, don’t sound like anything I would ever say. When was the last time you thanked a coworker in a note for their “toil of hardship”? We just don’t write like that.

But there’s a good reason the words I bolded are still in many of the English Bibles on our laps. To understand why, we need to read the Scriptures in the language of the Lamogai people of Papua New Guinea.

If you don’t happen to be one of the 4,000 or so people on the planet who speaks Lamogai, Dave Brunn will help you out.

Lessons from a missionary Bible translator

Brunn is a missionary Bible translator who helped bring the New Testament into the Lamogai language. His deep experience with a non-Indo-European tongue qualifies him eminently to deliver a helpful insight about the Greek genitive, and about Bible translation in general.

Brunn writes,

We have all been told that New Testament Greek is a precise language. That is true in some areas of the language, but it is not true of the genitive construction. (One Bible, Many Versions, 138)

Especially if you commonly use more “literal” English Bible translations (NASB, ESV, NKJV, RSV, etc.—the kinds that preserve original language ambiguities), you’ll recognize the genitive construction—and you’ll recognize it even if you don’t know Greek. It goes like this:

X of X

Brunn comments that the “genitive in Greek is commonly used to show simple possession, and in those cases, it is straightforward.” Here are a few biblical examples (run this search to find them all for yourself):

He entered the house of God (Matt 12:4)

I am the God of Abraham (Matt 22:32)

The precious blood of Christ (1 Pet 1:19)

But, Brunn points out, “in other contexts, the Greek genitive often has two or more possible meanings.” In other words, it isn’t precise. It is at times inherently, purposefully ambiguous. He points to 1 Thessalonians 1:3 (NASB), and note the three genitive phrases:

…constantly bearing in mind your work of faith and labor of love and steadfastness of hope in our Lord Jesus Christ in the presence of our God and Father.

The NASB follows the Greek quite literally when translating these genitives. And English (in part, Brunn says, because English is in the same language family as Greek—and in part, I’ll posit, because the Bible has influenced our mother tongue) can kind of handle the literalness.

But literal translations of these genitive phrases are particularly bad in Lamogai. Brunn says,

In Lamogai, a literal translation of these three phrases would sound like nonsense. For example, the phrase “labor of love” would sound like “labor that is possessed by love.” And “steadfastness of hope” would sound like “steadfastness owned by hope.”(138)

That would be gibberish. Gobbledygook. Greeklish.

The grammar of Lamogai doesn’t permit a literal translation here, as English (again, kind of) does. Lamogai forces the translator to make an interpretive decision among various options. The translator has to figure out what “labor of love” means before translating. Brunn lists out the options:

- They labor because of God’s love for them.

- They labor because of their love for God.

- They labor because of their love for others. (138)

If some Christians consider it a mark of faithfulness that a Bible translation preserve inspired ambiguities, then at least in Lamogai, at 1 Thessalonians 1:3, it’s impossible. The translator must choose.

And here’s the real insight in Dave Brunn’s point about the genitive (emphasis mine):

On one hand, it might be safer for a translator to leave [a] phrase ambiguous because we do not know for sure which meaning Paul intended. On the other hand, if hundreds or even thousands of other languages require that an interpretive choice be made, is it wrong to do the same thing in some English versions? If preserving the ambiguity of the Greek genitive were a requirement of faithfulness and accuracy, wouldn’t God have made sure that every language in the world was capable of fulfilling that requirement? (139)

It isn’t necessarily faithful to translate genitive constructions with “of.” It’s merely useful—at some times, not all, and for some Bible study purposes, not all.

Testing a hypothesis in Logos

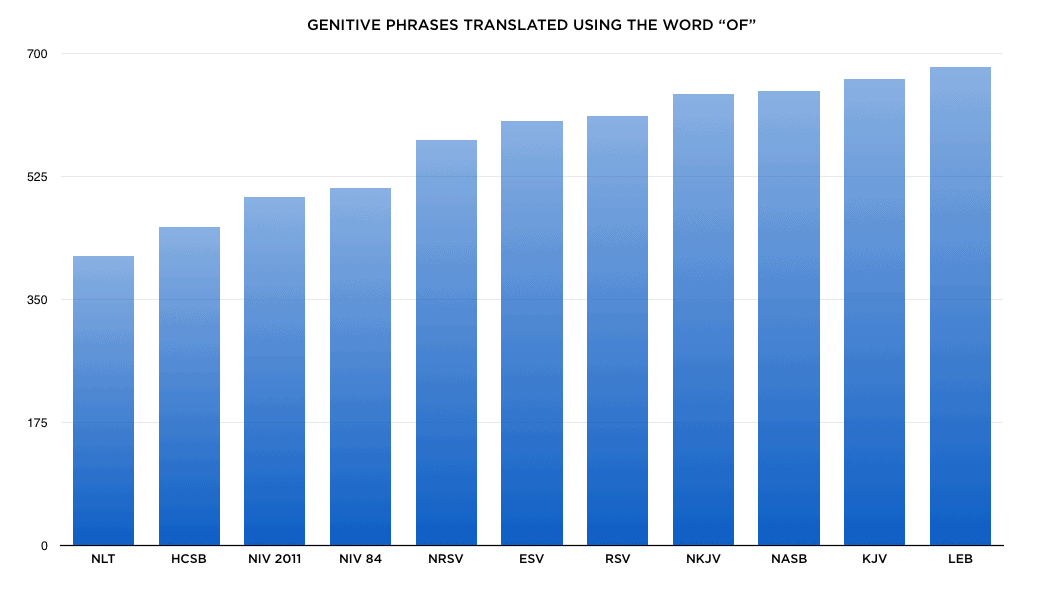

So I’ve got a hypothesis: one marker of the “literalness” or lack thereof of a Bible translation is how often it uses the word “of” to translate possessive genitive phrases—in other words, how often it’s willing to sacrifice a little English readability in order to maintain a little inspired ambiguity.

To be fully accurate, I’d have to examine every genitive in the New Testament. I confess I haven’t done that. For now, however, I’ll just take the first step in confirming (or not) my hypothesis: instead of examining, I’ll count.

Let’s search Logos for every possessive genitive phrase in the Greek New Testament, and let’s see which English translations use the word “of” the most often when translating those phrases. I’m predicting that the more literal English Bible translations will probably do so more often than will the less literal ones.

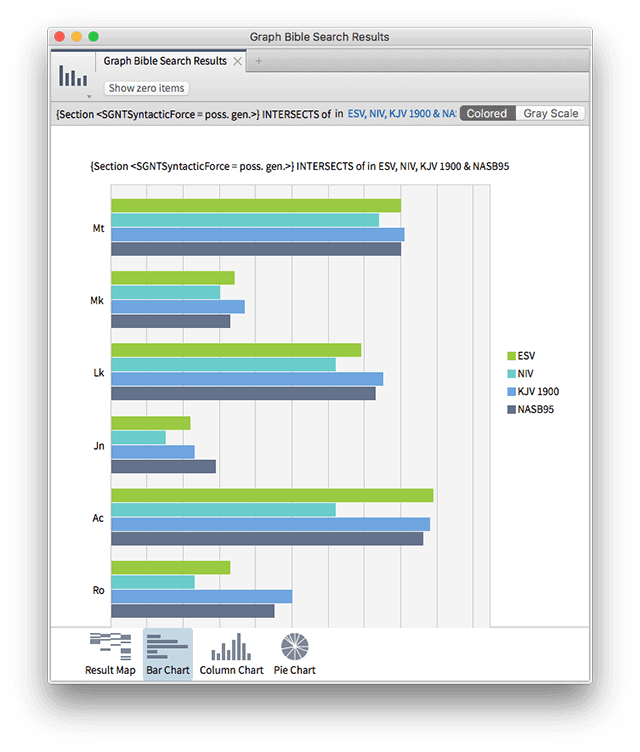

Logos Bible Software can search not just for genitives but, through the Lexham SGNT Syntactic Force Dataset, for specific genitive constructions such as possessives. How?

- If you know the search terminology, you can type it directly:

{Section <SGNTSyntacticForce = poss. gen.>} INTERSECTS of

- If you are a normal person with normal proclivities and a social life and you therefore don’t know the search terminology, just call up a search window, and a search cookbook will appear showing you how to run dozens of searches. The possessive genitive, however, isn’t currently one of them (though the genitive absolute is).

- So my favorite way of searching for a very precise grammatical feature in Logos is generally to find it first in the Bible text, right click it, select that grammatical feature (because the text of Scripture is so thoroughly tagged), then run a search for it. That’s what I did to find the genitives of possession.

I took the search terminology thus created and then added “INTERSECTS of,” which searches for the places of “intersects” those genitives of possession. That’s how I got this search:

{Section <SGNTSyntacticForce = poss. gen.>} INTERSECTS of

I ran the search in my top Bibles and graphed the results. This is what I found:

Conclusion

Somehow even when I try to stay in equine-free zones (and I don’t try very hard), my hobby horses manage to come trotting in. I see in all this genitive stuff another good reason to End Bible Translation Tribalism. It’s valuable to use Bible translations that preserve ambiguities, especially if you haven’t used them before. It’s important to puzzle through the meaning of genitives such as:

- “steadfastness of hope”

- “fruit of the Spirit”

- “obedience of faith”

It’s also valuable to use Bible translations that eliminate ambiguities and choose good interpretive options for you, because the whole point of translation is understanding. Even if you end up disagreeing with the less literal Bible translation in your hands, its interpretive renderings of these phrases will force you to think about what they mean:

- “Enduring hope”

- “Fruit the Spirit produces”

- “The obedience that comes from faith”

A fully word-for-word translation is an impossible ideal; it can’t exist in any language, and this is particularly true if that language isn’t already similar to Greek or Hebrew by being related to them. As Brunn says,

If the only faithful translation is one that is primarily word-focused like the NASB, ESV, or KJV, then most of the world’s languages cannot have a truly faithful translation [because they’re not in the Indo-European language family like Greek or the Afro-Asiatic family like Hebrew]. That would mean the majority of languages designed by God are inherently deficient, unable to communicate spiritual truth in a way that is faithful to the original.

What kind of Bible translation is best, literal or not-so-literal? At least when it comes to genitives of possession, I’d say: Yes.

Get started with free Bible software from Logos!

See for yourself how Logos will help you discover, understand, and share more of the biblical insights you crave. Compare translations, take notes and highlight, consult devotionals and commentaries, look up Greek and Hebrew words, and much more—all with the help of intuitive, interactive tools.