Neutrality is a myth.

Put in biblical terms, either you love the Lord or you don’t. Every thought you think, every choice you make, every word you say, flows from that heart and is determined by its fundamental direction, whether toward God or away from him. There are no fully objective human arbiters of opinion.

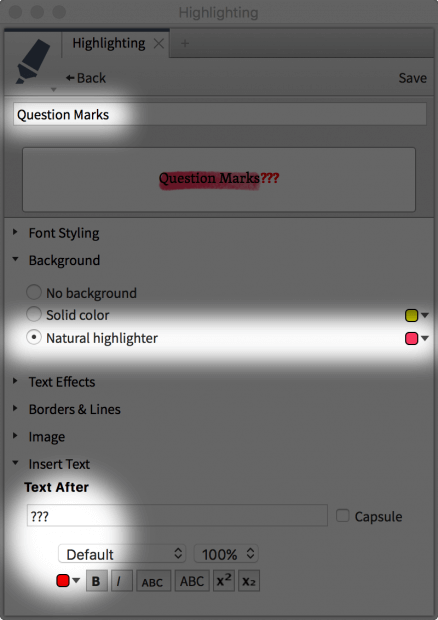

And yet even evangelicals who share this conviction sometimes slip into a mythological world in which neutrality is possible. I’ve developed a special highlighting style in Logos to mark these little slip-ups, because I just can’t let such statements go by without scrawling out my disapproval. (I’m an emotional reader, not just an analytical one.)

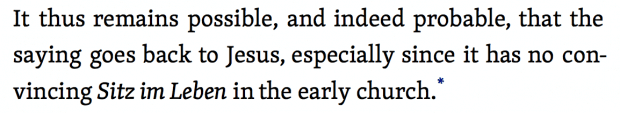

I’m not questioning the sincerity, salvation, or scholarly acumen of those who make such claims to neutrality. (That’s why I won’t be naming names in this post.) I’m just questioning whether it’s truly evangelical to say, for example, the following about a saying of Jesus in Luke:

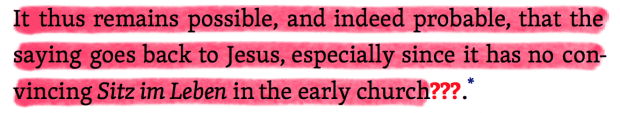

That was written by a respected evangelical commentator in an otherwise excellent commentary. But, emotional reader that I am, I marked it up:

Here’s what I did: I made a bright-red highlighter style, added some red question marks into it, and assigned it to the shortcut key Q, for questionable.

Can you see why I would call this statement questionable? This evangelical scholar says the historicity of this saying of Jesus reported by Luke is “possible, and indeed probable.” And one of the major reasons he thinks so is that he can’t imagine why the early church would have made it up.

What I’m critiquing here is, of course, what used to be called higher criticism—”the critical study of biblical texts, especially the evaluation of questions such as authorship, date, sources and composition.“ (Pocket Dictionary of Biblical Studies, Grand Rapids: InterVarsity Press, 57) I am not questioning all such criticism. Form and source criticism, as well as questions of author and date are all valid domains of inquiry into the Bible.

But here’s my point, and it’s by no means original to me: if no academic discipline is neutral, and if evangelicals are distinguished by their view of biblical authority, then the authority of the Bible ought to extend to biblical studies methodology, not just to biblical studies conclusions. It is the spirit of our secular age to claim objectivity about certain matters of history and science, such as the historicity of biblical events. But it isn’t neutral, dispassionate, and objective for someone to step back and weigh the validity (as opposed to the interpretation) of biblical statements. If God spoke the words of Scripture, and if we are to love him with all our hearts, “dispassion” is disobedience. (Not to put too fine a point on it.)

I’m not saying that we should let our passions run wild and outstrip our thinking, or that non-Christian academics are incapable of saying anything valuable or insightful about the Bible, or that everyone who loves the Lord will get his exegesis right all the time. I’m saying that we are told to love God with our minds (Matt 22:34–41): affect and cognition should not be dichotomized.

When secularism demands that all apparently religious presuppositions (such as “in Scripture God speaks authoritatively”) be set aside in order for something to count as scholarship, I can’t help but think of one of my favorite lines from Stanley Fish:

If you persuade liberalism that its dismissive marginalizing of religious discourse is a violation of its own chief principle, all you will gain is the right to sit down at liberalism’s table where before you were denied an invitation; but it will still be liberalism’s table that you are sitting at, and the etiquette of the conversation will still be hers. That is, someone will now turn and ask, “Well, what does religion have to say about this question?” And when, as often will be the case, religion’s answer is doctrinaire (what else could it be?), the moderator (a title deeply revealing) will nod politely and turn to someone who is presumed to be more reasonable. (“Why We Can’t All Just Get Along,” First Things, Feb 1996)

(Note that Fish is not talking about a particular political party but about “classical liberalism,” which includes most major political viewpoints in American history. This is not a political but a philosophical point.)

Religion is necessarily doctrinaire because at its heart, the Christian message can’t be proven empirically. Jesus’ resurrection is publicly available history (1 Cor 15:5–7), most certainly, but the gospel demands that we believe also that that resurrection had a particular theological significance (1 Cor 15:3). This truth can only be accepted on authority. And people have a habit of accepting the authorities that accord with their loves.

Common ground

Here I enter mind-reading territory—but only in an effort to lovingly believe the best. I suspect the evangelical commentator I first quoted above, the one who concluded that Jesus probably said what Luke said he said, was making a sincere attempt to meet unbelieving academics on their own ground. And he was doing this, I think, in an effort to reach out to them and persuade them to trust and obey these and other words of Christ.

And it has happened. Higher critics of Scripture have repented of their methodological naturalism and have taken every thought captive to Christ. Eta Linneman comes to mind. Jesus’ call to repentance (Mark 1:15), she saw, goes deeper than our conclusions. As Vern Poythress says in his intro to Apologetics to the Glory of God, we can never go off duty as Christ’s disciples, bracketing out our belief in Christ. And as Tim Keller shows in The Reason for God (and elsewhere), non-Christians don’t bracket out their ultimate beliefs either. Nobody’s neutral.

Mark L. Ward, Jr. received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the church as a Logos Pro. He is the author of multiple high school Bible textbooks, including Biblical Worldview: Creation, Fall, Redemption.

Get started with free Bible software from Logos!

See for yourself how Logos will help you discover, understand, and share more of the biblical insights you crave. Compare translations, take notes and highlight, consult devotionals and commentaries, look up Greek and Hebrew words, and much more—all with the help of intuitive, interactive tools.