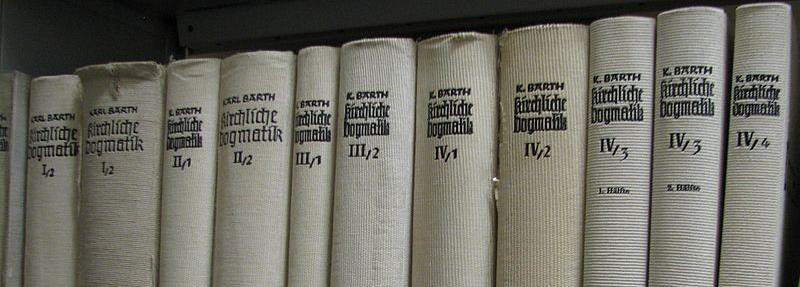

Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics (CD) is arguably the most important product of twentieth-century theology. It is difficult to describe adequately its enduring influence on academic theology. What Barth called his opus imperfectum never came to completion, but concluded abruptly upon his death at a towering thirteen volumes and nearly 10,000 pages.

Originally published in German as Die kirchliche Dogmatik, the English translation is known for its long, winding sentences that lead the reader through a string of interconnected and circuitous thoughts. Barth’s CD is also known for its social, historical, political, ecclesial, and theological context that engages hundreds of named and unnamed interlocutors over the more than 30 years of its composition.

So how does one begin to “break” Barth (or at least break into CD)?

Let me pass along five suggestions from a handful of experts who have benefitted me most. Armed with the following tips and a healthy dose of Spirit-inspired courage, the theologian can do no better than to sit down with one of Barth’s volumes, crack it open, and get to the hard yet rewarding work of reading.

Breaking down the CD

Just looking at those thirteen volumes on a shelf can be enough to frustrate the potential reader.1

Before diving in, it is helpful to get a lay of the land. To begin with, despite appearances, those thirteen volumes are really only four volumes (represented with Roman numerals), each representing a particular doctrine and divided into part-volumes (represented with Arabic numerals).

Here are summaries of each volume provided by Joseph Mangina in his excellent book, Karl Barth: Theologian of Christian Witness (WJK, 2004):

Volume I

The Doctrine of the Word of God (divided into two part-volumes): This is Barth’s ‘prolegomena’ or account of what theology is and how it knows what it knows. CD I/1 begins with God’s self-revelation as Trinity—the answer to the question, ‘how is it possible for human beings to know God?’

The account of revelation spills over into CD I/2, which concludes with a look at the authority of Scripture, the place of Christian doctrine, and the task of theology itself.

Volume II

The Doctrine of God (divided into two part-volumes): The whole doctrine is an account of God’s being, following the consistent rule: God is as God acts. CD II/1 revisits the question of God’s ‘knowableness’, and also describes the divine attributes or perfections (holiness, eternity, glory and so forth).

CD II/2 sets forth the doctrine of God’s electing grace in Jesus Christ. The volume concludes with exploration of God’s commandment, the first of several treatises on ethics.

Volume III

The Doctrine of Creation (divided into four part-volumes): CD III/1 deals with God as Creator, including major expositions of the creation stories in the first two chapters of Genesis.

In III/2 Barth sets forth his theological anthropology, or doctrine of the human person.

CD III/3 addresses a miscellany of topics pertaining to creation, including providence, evil, and ‘angelology’. The doctrine concludes with CD III/4 on the ethics of creation: what is required of us precisely in our relation to God as Creator.

Volume IV

The Doctrine of Reconciliation (divided into four part-volumes): This is a carefully structured volume. CD IV/1 describes reconciliation or atonement as a gracious divine action: the self-humbling of the Son of God.

In CD IV/2 Barth describes this same action from its human side, as Jesus, and in him all human beings, is exalted to fellowship with God.

CD IV/3 describes Jesus Christ as the God-man, present and powerful in human history.

CD IV/4 presents the ethics of reconciliation, published in fragmentary form after Barth’s death.

Volume V

The Doctrine of Redemption: This volume was planned but preceded by Barth’s death in 1968. Most versions label the index volume, Volume V.

One doctrine at a time, in detail

Knowing the structure is helpful, but where to begin? Much like any work the size of the CD, it need not be read from beginning to end. I have found it personally helpful to read the first 125 pages of CD I/1 (Barth’s explanation of prolegomena and his initial reflections on the Word of God) in order to get a sense of his method.

However, Eberhard Busch suggests that “it is relatively unimportant where one chooses to start reading.”2

Mangina reminds that Barth often remarked, “Latet periculum in generalibus,” or, “danger lurks in generalities.”3 The same is true of reading the CD.

The best approach is to focus on one particular doctrine at a time, and to give it detailed attention. Busch agrees with Mangina: “It is much better to read a small portion and understand it well than to read a large part superficially.”4

Here it is also helpful to know that Barth thinks in what are commonly designated paragraphs, represented by the § symbol. These are not “paragraphs” as the word is commonly used, but rather blocks of argument that can sometimes run for hundreds of pages (!). Thus, focusing on those paragraphs as distinctive blocks of argument within a distinctive doctrine is the suggested strategy for getting started.

Understand Barth’s argumentation and motivation

Barth is particularly averse to neat and tidy dogmatic summaries, and this is intentionally reflected in his style of argument. This may be a source of frustration to his reader.

Yet it is for good reason. While he is committed to an understanding of theology as Wissenschaft, or science, that does not mean it is characterized by objectivity and certainty. Barth is repetitive in his announcement that the object of theology’s study is God. Thus, it should be expected that theology would defy simple and self-confident propositions.

This gives way to winding prolixity and circuitous sentences that hover above conclusions, sometimes without ever quite landing on them. In this way, “Barth moves ahead by constantly circling around his subject, in order to follow the dynamics which inheres in it.”5 The style is an intentional reflection of an epistemic modesty regarding what can be said concretely about God.

That same modesty is demonstrated when viewing the CD as a whole. Busch says that Barth is resistant to offering anything resembling a comprehensive system or final conclusion. His arguments are dialogical in character and are more concerned with opening the conversation than getting the last word. The nature of dogmatics is always open to reconsideration in light of the Word of God.

This open-ended and continuous nature of the dogmatic enterprise is well represented by the unintentionally incomplete nature of the CD as a whole. In one sense, even if Barth had lived long enough to write Volume V, the project would have never been complete. For Barth’s life and his theology, he always wanted God to get the last word.

Mangina notes that Barth’s style is also a function “of the way Barth’s mind works. He tends to think in long, spiraling arcs of reflection, a trait that at times lends his writing an almost musical, contrapuntal quality…” “This,” Mangina continues, “is also why the Dogmatics largely defies attempts at paraphrase.”6

Repetition is another characteristic of Barth’s style. Busch claims that Barth “is always seeking to say the same thing differently. At every point, from various angles, it focuses on the one totality of the Christian confession of faith.”7

With something more specific in mind, Hunsinger makes a similar point, namely, that reading the CD is all about pattern recognition.8

This means that despite its sprawling volumes, many of the same concerns, themes, and ideas appear repeatedly.

Be prepared for solid exegesis

The modern departmental fragmentation between biblical studies, historical theology, practical theology and the like, going back to Schleiermacher, would have been anathema to Barth. His strong concern for historical theology and practical theology are evident throughout the CD and are to be expected.

Yet, what may be of surprise to first readers is Barth’s burden to ground his theology in biblical exegesis. Even a cursory glance at the sprawling scripture index, which occupies much of a supplemental volume, usually labeled Volume V, makes the point nicely.

For example, take Volume III – The Doctrine of Creation. It is greatly occupied by an exposition of Genesis 1 and 2. Similarly, Volume II/2 is Barth’s grappling with Romans 9-11 as he attempts to articulate the place of Israel in the heilsgeschichte. Barth’s theological method is grounded in the Word of God revealed in Jesus Christ and witnessed to in Holy Scripture. Theology cannot be done independently of the revealed Word of God.

This commitment to biblical exegesis was a hallmark of Barth’s life and teaching. When expelled from Germany in 1935, due to his unwillingness to take the oath of loyalty to Hitler, his parting words to his students were, “exegesis, exegesis and yet more exegesis! Keep to the Word, to the scripture that has been given us.”9

Read about Barth’s life, development, and ministry

Become familiar with Barth’s life, theological development, and personal ministry. This fifth suggestion runs the risk of sending the student back into the secondary literature and away from Barth himself; but a disciplined detour into the details of Barth’s life is an important part of understanding the motivations that undergird many of his arguments in the CD.

Barth is known for his break with the liberalism of his day, his critiques of modernism and its influence on theological method, and his staunch rejection of the analogia entis, natural theology, and apologetics. Yet, to understand those convictions it is important to know something of the intellectual, theological, historical, and political milieu that Barth occupied.

Barth’s firm convictions and impassioned arguments can surprise the reader who is unfamiliar with the various backstories. Therefore, it is worth getting some historical and biographical context. Here, one can do no better than Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (Wipf & Stock, 2005). Still, one need not feel barred from opening the CD without such supplemental background knowledge.

What is left but to get started reading in the CD? What tips or advice would you offer for novice readers of Barth? Leave a comment.

Additional essential readings in Karl Barth:

- Karl Barth’s The Epistle to the Ephesians, with introductory essays by Francis Watson and John Webster

- John Webster’s Word and Church: Essays in Church Dogmatics

- Some versions of the CD have broken the work into even as many as 31 smaller part-volumes. However, the standard method of referencing the CD reflects the outline provided by Mangina listed here.

- Eberhard Busch, The Great Passion: An Introduction to Karl Barth’s Theology, 39.

- Mangina, 24.

- Busch, 39.

- Ibid.

- Mangina, 23.

- Busch, 39.

- George Hunsinger, How to Read Karl Barth (Oxford University Press, 1991), 6.

- Eberhard Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 1994), 259. As cited in Mangina, op. cit., 4.