As college sophomores, my three closest friends and I believed we were God’s gift to the small congregation we had decided to join. Sure, in addition to the many elderly congregants, there were a few young families in the membership. But we were college students. We brought the energy, the vitality. Yet though we didn’t know it at the time, our need for those older folks far exceeded their need for us.

In the following Bible study, we will take a deep dive into Psalm 71 to better understand why churches need aged saints. We will begin with some background work and introductory observation and interpretation, but we will focus on honing our ability to make rich and satisfying applications.

Background

The book of Psalms is a collection of liturgical and devotional poems, organized into five divisions or “books” (Psalms 1–41, 42–72, 73–89, 90–106, and 107–150). Psalm 71 comes near the end of Book Two, and its distinguishing feature within that collection is its lack of superscription. Nearly every other poem in Book Two has a superscript identifying the poet and/or instructions for the poem’s performance.1 The Spirit who inspired the creating and collecting of these poems did not see fit to reveal any particular historical circumstance associated with this poem.

Yet the poem itself gives some clues regarding its authorship. Read the Psalm 71 now in its entirety five times, writing down anything you learn about the poet from the hints within the text. Pay special attention to the poet’s age and life circumstances. Jot down your ideas before moving on.

Did you notice references to the poet’s age in verses 5–6, 9, and 17–18? He uses the phrase “from my youth”2 a few times, which would be a funny way to describe yourself if you were young. The ESV translation of the verses about old age (9 and 18) makes it hard to tell whether the poet is currently in his old age or whether he is looking ahead to it. However, the general consensus of Hebrew scholars, summarized here by Michael Wilcock, is that “this, alone among the psalms, is obviously the composition of an elderly person.”3

Combining these complementary insights—the lack of historical situation and the old age of the poet—we could read this poem as the reflection of a faithful, elderly saint reviewing a lifetime walk with God.4 No particular situation led to the poem’s composition, and no particular person (such as a choirmaster—see Pss 68, 69, 70, etc.) is intended to read it. Psalm 71 is an everyman poem, for every situation, for every reader.

Introductory observation and interpretation

One key observation is the theme of the poet’s influence on the next generation (especially in verses 7–8 and 14–18). In verse 7, the poet has been “as a portent to many”—a sign, a model, a living and breathing parable of God’s protective refuge.

To draw out this theme further, let’s examine the psalm’s flow of thought. Read through Psalm 71 again, taking note of the poem’s progression from topic to topic. What main topics do you see being addressed by the aged psalmist? Unfortunately, the poem is remarkably difficult to break into stanzas, as evidenced by the fact that every commentary I checked offers a different outline.5 So we’ll have to do the best we can to follow the flow from topic to topic.

Try to write a simple outline of the poem’s topics. The goal is not to list every possible concept we could explore through the poem, but to capture the main ideas of each group of verses.

Now look at each section of your outline and consider how the psalmist is a portent to his readers in that area. How is his life, described with the hindsight of age, meant to establish a pattern or example for our lives? Create a list of ways in which the poet wishes others to learn from his example. This will lay useful groundwork as we move into application.

Here is the flow of thought I see in Psalm 71. You are free to adjust it if you believe I’m missing aspects of the text, but I’ll use this as the basis for our subsequent application.

Churches need aged saints who:

- Cling steadfastly to Christ (verses 1–6)

- Prove that enemies are not all-powerful (verses 7–14)

- Recall the deeds of God (verses 15–18)

- Foresee a happy future (verses 19–24)

Charles Spurgeon summarized the poem well when he wrote: “We have here the prayer of the aged believer who in holy confidence of faith, strengthened by a long and remarkable experience, pleads against his enemies and asks further blessings for himself. Anticipating a gracious reply, he promises to magnify the Lord exceedingly.”6

Application

Let’s face it: Application is challenging.

We have the challenge of inertia. The Holy Spirit wrote the Bible in order to move us toward Christ and his kingdom. But sometimes we’d rather stay still. And other times, we’re already moving in a different direction and don’t want to alter course. Careful observation and accurate interpretation can only show us the path. Application is the outworking of a faith that recognizes the value of walking that path.

Before we proceed with asking application questions, please take some time to pray for God’s help.

- Open yourself to his instruction (“Open my eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of your law,” Ps 119:18).

- Confess your dullness of heart and slowness to believe (“I have gone astray like a lost sheep; seek your servant, for I do not forget your commandments,” Ps 119:176).

- Ask God to remind you that life change is worth the effort (“This is my comfort in my affliction, that your promise gives me life,” Ps 119:50).

- Remember that application is not primarily about getting more of the Bible into your life, but getting more of the Lord as your inheritance (“The Lord is my portion; I promise to keep your words,” Ps 119:57).

- Profess your dependence on God’s word, lest you lose your hold on reality (“I open my mouth and pant, because I long for your commandments,” Ps 119:131).

- Dedicate your entire self anew to the joy of obedience (“With my whole heart I cry; answer me, O LORD! I will keep your statutes,” Ps 119:145).

The need for specificity

One last challenge to overcome is our tendency to be so generic and abstract in our application that nothing concrete ever changes in our lives. Of course, we all need to improve at loving God and loving our neighbor. Though those two commands are the most important in all the law (Mark 12:28–31) and all the Law and the Prophets depend on them (Matt 22:20), we still must apply them specifically to the details of our lives.

Moses drew out the implications of love for God in regulations for weekly and monthly sabbaths, judicial sanctions for idolaters, and the practice of collecting funds for the sanctuary when taking a census. He explained love for neighbor not only in grandiose principles but also in mundane prescriptions such as fencing your roof patio, replacing borrowed items you accidentally broke, and returning your enemy’s stray donkey.

From Paul’s letters (especially Eph 4:17–5:20 and Col 3:1–17), we learn that one particular way to get more specific is to think of obedience, or application, as including something to put off and something to put on. So one way to convert general principles into specifics is to consider what you ought to stop doing or believing, and what you ought to start doing or believing instead.

Because love for God and love for neighbor are intensely practical matters, our application must move beyond generic principles to concrete changes in belief, value, and practice. In a magazine article, where I have not met you face-to-face, I can take your application only so far. You will have to complete that particular work with God’s particular help (and perhaps the help of wise counselors in your life).

The two directions

If you’ve ever gotten into a rut in your Bible application, where your application for every passage begins sounding the same (“I’ll get up earlier to read my Bible”; “I’ll find a way to mention Jesus to my coworkers”; “I’ll stop yelling at my children”; or “I’ll try not to be such a couch potato”), one way to stretch yourself is to think of application in two directions.

I’ve already mentioned the inward direction, which boils down to love for God and neighbor. Inward application is all about how you should change in light of this text.

It’s also worth considering the outward direction, which seeks to obey not only the two greatest commandments but also the great commission (Matt 28:19–20). The Bible was written not only for individual believers, but also for believing communities. So we ought to consider how a passage can train us to have greater influence, more sincere compassion, and more winsome persuasion to help others walk with Christ.

So, your next assignment on Psalm 71 is to think about the psalm in light of both directions for application.

- How does the poem call you to change? How does it inspire you to better love God and your neighbor?

- How does the poem call you to be an agent of change for others? How does it equip you to more effectively make disciples of Jesus Christ in your spheres of influence?

After asking those questions broadly and writing down some answers, take your thematic outline of the poem (or use my outline) and walk through each section of the poem.

- Reread the first section of the poem. Consider and write down: How should I change? How can I help others to change?

- Do the same for the second and each subsequent section of the poem.

Perhaps, with these two directions, you’re beginning to see some avenues for application you may not typically have considered. But perhaps you still feel stuck and unsure where to go next. The three spheres will help you to get even more specific.

The three spheres

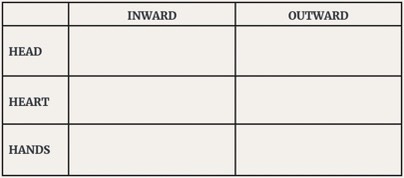

To prevent unhelpful reductionism, I prefer to think of application in three spheres: the head, the heart, and the hands. Head application represents everything you think and believe. Heart application represents everything you love and value. Hands application represents everything you do.

What do I mean by “unhelpful reductionism”? Sometimes, people think application only and always requires actions and behaviors. If your application doesn’t hit your daily task list, they might think, it’s not personal or practical enough. Other times, people think application only and always requires learning proper doctrine and ensuring the purity of our confession.

If your application doesn’t delve into the depths of the glory of God in the face of Christ, they might think, it’s not rigorous or faithful enough. Yet other times, people think application only and always requires character to be king. If your application doesn’t make you the kind of person Christ would have you be, they might think, it’s either legalistic or overly intellectual.

I confess I am painting an exaggerated picture, but I have truly found individuals and Christian communities that tend to feel most comfortable applying the Bible in only one of these ways. Yet God commands us to grow in all three areas. All three spheres consist of legitimate applications of the Bible. So when I want to exercise my application muscles, I make sure to work out in all three spheres, striving to make progress in all three.

So when I want to exercise my application muscles, I make sure to work out in all three spheres, striving to make progress in all three.

The matrix

When you combine the two directions with the three spheres, you get a matrix for application, giving you six lines of questioning to pursue.

Of course, you don’t have to fill in all six boxes every time you study the Bible. But perhaps you could aim to apply the Bible in all six boxes evenly over time. And when you feel stuck or in a rut, consider using this matrix to suggest realms of application you wouldn’t otherwise have considered.

The Psalm

Let’s get back to Psalm 71 and practice applying it with the complete matrix in mind. To do this, we’ll work through the poem section by section.

Churches need aged saints who cling steadfastly to Christ (verses 1–6)

Inward head: Are you surprised when life is hard? Do you functionally believe that if you are faithful to Christ, life should be relatively uncomplicated? Who are the people in your life who have demonstrated a long life of clinging to Christ, who can encourage you to do the same?

Inward heart: What do you trust to be your refuge when life is hard? How much value do you think there is in having intimate relationships with elderly saints? Not just out of pity or for company, but for the purpose of deriving inspiration from their example?

Inward hands: What are your coping behaviors when life is hard? How often do you spend time with elderly saints who show you how to cling steadfastly to Christ?

Outward head: Do you believe you have anything to offer the body of Christ, even as your faculties slow, your senses dim, and your body deteriorates?

Outward heart: How can you avoid the folly of becoming self-made and self-reliant? How can you avoid bitterness at life’s miseries? And especially: How can you encourage in others, including the aged, the idea that they can find their treasure in Christ and avoid a self-centered or critical spirit?

Outward hands: How can you better communicate what is good about the younger generation, even if it is different from your own generation? How can you speak affectionately and winsomely of your life of refuge in the Lord Jesus?

Churches need aged saints who prove that enemies are not all-powerful (verses 7–14)

Inward head: Do you believe the enemies of Christ are more powerful than the people of God? Do you have reason to believe God will ever cast you off?

Inward heart: When enemies succeed, are you tempted to think God has abandoned you (verse 11)? Who can help you? How can your walk with God help you not to be so afraid of people not liking you?

Inward hands: The real measure of your trust in God in the face of direct attacks is your choice of solace. When your anxiety and stress get out of control, what is most likely to help you settle down: a prayer meeting (verse 12) or a bowl of ice cream? Or something else?

Outward head: Can you see how much the younger generation needs role models for dealing with enemies?

Outward heart: How can you show your church an aged saint who has faced many trials without cowering in fear on all sides? What opportunities do you have to show courage in the Lord?

Outward hands: How can you speak graciously into the younger generation’s fears and anxieties? How can you do this without a self-righteous attitude (“back in the good old days …”)?

Churches need aged saints who recall the deeds of God (verses 15–18)

Inward head: Where can you observe the world telling you to turn inward and trust yourself? What good will that do for you?

Inward heart: How can you find greater inspiration and courage from the mighty deeds of God, more than from your own accomplishments?

Inward hands: Where can you turn, or what relationships can you cultivate, to ensure you will be constantly reminded of the mighty deeds of the Lord? How can you establish safeguards to avoid forgetting the Lord’s deeds?

Outward head: Do you think it will do any good to remind others of what they already know and have heard before? Why or why not?

Outward heart: How can you persevere in proclaiming God’s might to another generation?

Outward hands: The body of Christ needs to see an older generation that doesn’t follow its heart and turn inward like younger folks tend to do. How can you show them? What opportunities do you have to speak of God’s deeds of salvation? Speak!

Churches need aged saints who foresee a happy future (verses 19–24)

Inward head: When you envision the future, do you see only more troubles and calamities, or do you see the resurrection (verse 20)?

Inward heart: What do you have or foresee that can compare to the God who has done great things (verse 19)?

Inward hands: How can you turn your anxiety and complaining about the future into song and praise? With respect to church life? Business life? Politics? Society at large?

Outward head: What do others see when they see you looking to the future? How do your troubles look in light of eternity? Do you understand what causes anxiety for younger folks, and do you have satisfying answers for their troubles? Can you offer them something better and more inspiring?

Outward heart: What are your greatest sources of grumbling? How can you show your church an aged saint who cannot despair in light of what God has in store for us?

Outward hands: How can you speak less of your troubles and calamities and more of your imminent resurrection? When words roll off your tongue, do people hear of God’s righteous help or of your heartache (verse 24)?

Conclusion

Perhaps you’re beginning to understand how rich and varied Bible application can be. We won’t usually have the time or space to pursue every possible avenue for application from every text. But that’s OK. It only means we’ll have plenty to consider, discuss, and practice, even ‘til we’re old and gray. There will always be a new generation, having the same need for these truths to resound and inspire. You and I can serve as portents to many, showing off the manifold grace and righteousness of our God who never fails us.

***

This article was originally published in the May/June 2021 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related articles

- What You Might Be Missing about “Blessed Is the Man” in Psalms

- Almost Home: What the Bible Does (& Doesn’t) Teach Us about Heaven

- Pray the Psalms with Your Church

Related resource

- Psalm 43 is the only other poem in Book Two with no superscription, but many commentators regard Psalms 42 and 43 as a single poem. Notice how Ps 43:5 repeats the refrain of Ps 42:5 and 11, thus suggesting the two psalms comprise a single three-stanza poem.

- This study quotes from the English Standard Version. Michael Wilcock, The Message of Psalms: Songs for the People of God, The Bible Speaks Today, ed. J. A. Motyer, vol. 1 (Nottingham, UK: InterVarsity, 2001), 246.

- Remember that “saint” is the Bible’s word for an ordinary believer—not a spiritual superhero—who has been justified by faith, united to Christ, and called to holiness (for example, Ps 31:23; Prov 2:8; Dan 7:21; Acts 9:13; Rom 1:7).

- Wilcock (246) goes as far as to label the lack of disciplined structure a privilege of the poet’s old age.

- Charles Spurgeon, The Treasury of David, vol. 2a, Psalms 58–87 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1968), 206.