Did you know God encourages righteous protest? If he didn’t want to encourage it, he wouldn’t have given his people the vocabulary of protest in their songs and prayers. In the following study of Psalm 80, we will take a close look at one of the many protest songs found in the book of Psalms. As we learn from it how to give voice to our objections in a godly way, we will also sharpen the skills of OIA (observe, interpret, apply) Bible study.

Overview of the Method

The OIA method of Bible study has three main parts:

- When we observe, we pay close attention to what the text says.

- When we interpret, we attempt to discern what the text means.

- When we apply, we labor to discover how the text ought to change us.

The segments below will guide you in a thorough study of Psalm 80 according to the steps of OIA. Each segment builds on previous segments, so it is important to work through them in order, perhaps one segment every few days. But as you internalize the skills for continued study of other texts, you may find the skills flowing more freely, not needing to follow a rigidly linear order.

Observation

Before we can attempt to grasp what a passage means, we must first learn to look at what it says. If you’re not sure what to look for, consider five categories:

- Genre

- Words

- Grammar

- Structure

- Mood

Genre

In the broadest sense, the Bible has only two primary genres: prose and poetry. In modern Bibles, prose is the term for everything that looks like this very paragraph—reaching all the way from the left margin to the right margin, with sentences wrapping around to the next line whenever needed. Prose tends to be plainly descriptive or explanatory.

Poetry, however,

Looks like this.

Line by line,

Like ants marching;

Margins wide as oceans.

Word pictures.

Take a look at Psalm 80 in your Bible.1 What genre do you observe?

While genre is perhaps the easiest observation you can make, it comes with momentous implications. What do you know about how poetry works? What should you expect from a poem? Why might someone choose to express their ideas through poetry instead of prose? What can poetry do for an idea that prose cannot? Keep the answers to these questions in mind as you continue studying this poem.

In addition, what does the first phrase in the superscript (“to the choirmaster”) suggest about what kind of poem Psalm 80 is?

Words

It is self-evident that literature consists of words, many words. But what is not quite as evident is what we should do with those words. What should we look for? What is there to observe? In this study, I’ll give you three techniques to get you started in your observation of the words.

First, I always begin by looking for repeated words. They’re not too difficult to find, and this exercise often bears much fruit in a brief time.

Stare at Psalm 80, reading and re-reading it four or five times. As you go, underline words or word families that are repeated. Don’t worry about minor words, such as “the” or “of,” which are necessary for English to work. Look for the meaty words, those given prominence through frequency. Develop a list before moving on within this article.

Here is a list of the most repeated (significant) words, generated by Logos 9 and using the ESV. How does your list compare?

- God (5 times)

- face (4)

- hosts (4)

- let (4)

- save/saved (4)

- shine (4)

- hand (3)

- out (3)

- restore (3)

Second, we can observe names and titles for the characters in a text. We have observed that “God” is the most repeated word in the poem, but that’s not the only name, title, or description used for him. List the additional names and titles of God used in this poem. What picture of God does the poet paint by means of those names and titles?

Third, try to observe allusions or quotations of earlier Bible passages. Biblical authors often invest rich meaning in a passage simply by echoing an earlier text that the readers would have been familiar with. This skill requires familiarity with the entire Bible, which comes in time as you develop a habit of broad Bible reading. In Psalm 80, the words “let your face shine” (verses 3, 7, 19) conjure up memory of the blessing God commanded the high priest to pronounce over the people of Israel:

The LORD bless you and keep you; the LORD make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you; the LORD lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace. (Numbers 6:24–26)

Perhaps you’ve already noticed further allusions within the poem (such as “vine” alluding to Hosea 10:1 and Isaiah 5:1–72; God’s “son” alluding to Exodus 4:22–23, 2 Samuel 7:14–16, and Psalm 2:7–9). Observing these allusions—or finding them through cross-references in your Bible edition—will pay dividends when it comes time to interpret the poem’s meaning.

Grammar

The most important grammar skill is the ability to identify the subjects and main verbs of each sentence. Let me get you started:

- Shepherd, give ear!

- You [Shepherd], shine forth!

- [You/Shepherd], stir up and come to save!

- God, restore!

- [God], let shine!

- Will you [God] be angry?

- You [God] have fed and given.

- You [God] make, and enemies laugh.

- God, restore!

- [God], let shine!

That covers the first seven verses. Can you complete the list from there?

Why does it matter that you learn to observe subjects and main verbs? Because that list will capture the main ideas of each sentence. It’s good to observe, for example, that God leads Joseph like a flock (v.1). But it’s even better to grasp the poet’s point—that he begs this divine Shepherd to listen to what he has to say (“Give ear”)!

Structure

In your examination of repeated words, you may have already made a significant structural observation: Most of the repeated words are actually part of larger phrases or sentences that are repeated:

- Restore us, O God; let your face shine, that we may be saved! (v. 3)

- Restore us, O God of hosts; let your face shine, that we may be saved! (v. 7)

- Restore us, O LORD God of hosts! Let your face shine, that we may be saved! (v. 19)

When a poetic sentence or verse is repeated like this, it is called a refrain. Poets use refrains typically to mark the structure of their poem. In the case of Psalm 80, the refrain serves to conclude each group of verses (each stanza). The three instances of the refrain therefore suggest three stanzas to the poem.

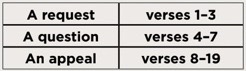

The content of each stanza affirms this three-fold structure. Verses 1–3 primarily make a request (Give ear … stir up your might and come to save us!). Verses 4–7 ask a heartbreaking question—How long will you be angry?—supported by a string of evidence (You have fed us with tears and made our enemies laugh at us). Verses 8–19 lodge an appeal that this behavior on God’s part does not appear consistent with his promises and history with his people.

Therefore, we could outline the poem’s structure as follows:

Though that third section seems quite long—more than twice as long as the first two sections—the fact that the refrain doesn’t occur until verse 19 leads us to keep verses 8–19 together. Perhaps continued investigation will reveal whether we ought to subdivide that third stanza further.

Mood

From your observation so far, what sort of mood have you seen communicated through the poem?

What sort of mood is communicated by phrases such as “how long will you be angry” and “tears to drink in full measure”? What other phrases in the poem communicate a similar mood?

And what sort of mood is communicated by phrases such as “you who lead Joseph like a flock” and “let your face shine”? What other phrases in the poem communicate a similar mood?

How do these two shades of mood fit together to create a broad mood for the poem?

Interpretation

The purpose of interpretation is not ultimately to satisfy our personal curiosities but to establish the chief message intended by the author and inspired by the Spirit of God. Therefore, the cardinal rule for interpretation is that interpretation must be based on and driven by what we have observed in the text.

Interpretation has three aspects to it:

- Investigate your observations through questions.

- Answer only those questions that are answered or assumed by the text.

- Determine the author’s main point in this text.

These three aspects are not meant to be conducted in a linear fashion, as if you must always complete the first before moving to the second, or that you must complete the second before moving to the third. Instead, the three aspects are like a spiral or cycle. The answers to some questions ought to generate more questions. All questions should drive you back to observe the text more closely—which then raises more questions that need answers. And even after you’ve determined the author’s main point, further observation, more questions, and clearer answers may lead you to reshape or refine your understanding of that main point.

For the sake of demonstration, however, let’s now simply work through the three aspects in order.

Ask questions

Remember the cardinal rule: Your interpretation must be based on your observation. The goal of your questioning is not to pursue your fancy in any direction whatsoever. Your goal is to get as curious as possible about what you have seen in the text, to ensure you understand what the author seeks to communicate.

So take one of your observations and pepper it with questions. I find three types of questions to be most helpful:

- “What” questions help to define the observation clearly.

- “Why” questions uncover the rationale or train of thought.

- “So what” questions draw out the implications of the author’s arguments.

Let’s start with the observation that “God” is repeated five times. We could ask:

- What God is he talking about? What is communicated about this God by means of the various names and titles for him in the poem? What does the poet believe about God, and what does the poet expect from God?

- Why does he speak to (or about) this God so much? Why does he use the title “God” in those particular places? Why doesn’t he use a different name or title for God?

- So what does he want people to understand about this God? So what case does he make for why this God is to be trusted? So what, besides this God, might people trust in to “come and save us”?

While you can investigate any observation, give special attention to investigating the structure. The structure is your best ticket to following the poet’s argument from beginning to end.

- What is the main idea of each stanza? What is the essential request of vv. 1–3? What is the heart of the question of vv. 4–7? What is he appealing for in vv. 8–19?

- Why does he request this (1–3)? Why would he ask such a question (4–7)? Why is he compelled to make this appeal (8–19)?

- So what does he want his audience to make of this request (1–3)? So what response does he seek to his question (4–7)? So what effect should this have on further appeals of God’s people (8–19)?

Keep going and see how many questions arise from your observation of the psalm.

Answer questions

When you’re ready to answer your questions, make sure to answer your questions from the passage. Don’t turn to any other passages just yet—except for those earlier texts specifically alluded to within Psalm 80. And don’t jump into concepts from systematic theology that would not have been clear to the original audience (there will be time for this later). Do your best to answer the questions in the way the original audience would have answered them.

This means you will not be able to answer every question. You will have to let some of them go if the text does not address them (or if the answers wouldn’t have been obvious or assumed by the original audience). For example: Where do “cherubim” (v.1) fit within the hierarchy of angelic command structures? While such a question may be attractive to the inquisitive mind—and useful to answer in another study, a topical one—it is clearly not a matter this poet set out to address.

Go ahead and observe the text more deeply to answer your interpretive questions (or to help you figure which questions to discard for now). Give particular attention to questions surrounding the structure and resulting train of thought.

Determine the main point

While the climax of observation might be crafting a clear and concise summary of the passage, the climax of interpretation is the crafting of a clear and concise main point for the passage. Don’t confuse the two: A summary simplifies what the passage says; a main point declares why the passage says it.

A great method for determining the main point begins with getting a clear sense of the structure. Then identify the main point of each structural unit. Then figure out how each unit logically connects to the next.

Here’s what that might look like for Psalm 80:

Stanza 1 (vv. 1–3)

- Summary: A request for God to listen, by using his strength to save them.

- Main point: We know where to find strength that saves.

Stanza 2 (vv. 4–7)

- Summary: A question about how long God will be angry with his people’s prayers for rescue.

- Main point: But we’re still being denied the strength that saves.

Stanza 3 (vv. 8–19)

- Summary: An appeal that this state of affairs appears inconsistent with God’s character and history.

- Main point: This isn’t how it ought to be.

Now, how does the main point of each stanza connect to the next? The second contrasts with the first, which leads to the dramatic and tender appeal of the third. This train of thought leads us to look to the third stanza for the overall main point. That third stanza bears the weight of the poem’s argument, while the first two stanzas are primarily paving the way for that appeal.

Now that I’ve done a lot of that work for you, I’ll let you finish the job. How would you state the author’s main point in a single, concise sentence? Perhaps I’ve already offered some help through the title and opening paragraph to this study.

Connect to the Gospel of Jesus Christ

Though I wrote above that Interpretation has three aspects, I’m now going to add a fourth. That’s because this fourth aspect truly comes after you’ve done the other three. Attempt this connection before you’ve identified the passage’s main point, and you may find yourself following some false trails.

Now that you have grasped the main point of Psalm 80, it is time to reference later passages of Scripture and the Bible’s larger theology. Can you think of any New Testament passages that show forth Jesus as the answer to the poem’s appeal? Where do we see God strengthening Jesus for the salvation of his people (e.g. John 12:27–33)? What do we know about the restoration Jesus has enacted for his people (e.g. Mark 9:11–13)? Can we still expect God’s face to shine on his people (e.g. 2 Cor 4:6, Rev 1:12–16)?

Application

Productive Bible study ought to result in change for God’s people and for the world. Strong observation and robust interpretation will compel vibrant application. In other words, if you have done well at the observation and interpretation skills, application should practically roll into your lap. But we can still stretch our application muscles to keep us from getting into a rut, applying every passage in the same general way (read my Bible, love God more, do right).

How does the main point of the passage, seen through the lens of the gospel of Christ, impact what you believe or should stop believing? (We can call this “head” application.)

How does the main point of the passage, seen through the lens of the gospel, impact what you worship, love, and/or value—or what you should stop worshipping, loving, or valuing? (We can call this “heart” application.)

How does the main point of the passage, seen through the lens of the gospel, impact what you do or should stop doing? (We can call this “hands” application.)

When attempting to apply the Bible, some people may habitually consider only one of those spheres, such as hands (a set of behaviors or items on a task list) or head (a set of doctrines). But all three spheres can be considered legitimate application, and most of us can deepen our skill at application to all three spheres over time.

In addition, consider application not only for yourself (personal change) but also for your world (relational influence). How can you continue making disciples of the Lord Jesus by calling others to put this main point into practice as well? Consider your children, parents, coworkers, neighbors, and fellow church members.

Conclusion

Now that I’ve guided you through the OIA method in a study of Psalm 80, it’s time to practice the method on your own with a different psalm. I recommend Psalm 46, which also uses a refrain as the main structuring device, and will therefore feel somewhat similar to Psalm 80.

***

This article was originally published in the March/April 2021 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related articles

- 3 Bible Study Methods to Jump-Start Your Time in the Word

- Pray the Psalms with Your Church

- Psalm 2: Its Meaning in the New Testament

Related resources