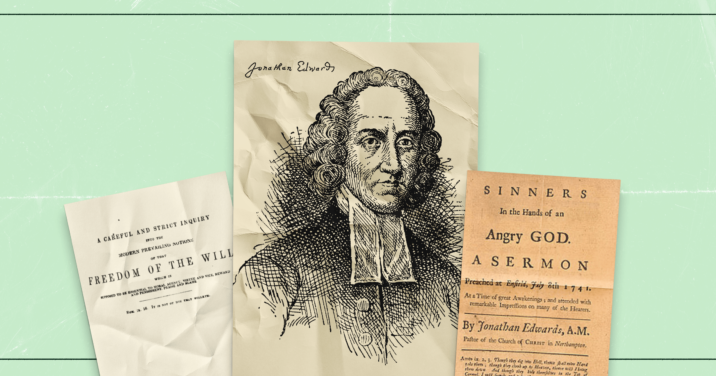

When Jonathan Edwards was 19 years old, he sketched out a series of handwritten resolutions, or personal vows, intended to provide structure to his Christian pilgrimage and guidance for his emerging ministerial career. Many of his resolutions reflect an admirable—if somewhat naive—enthusiasm: 70 lofty vows impossible to keep through human willpower alone. Who can pledge to “never to do any manner of thing, whether in soul or body, less or more, but what tends to the glory of God” by the sheer force of determination alone?

However much he may have failed to keep his own high standards, there is at least one resolution that Edwards kept steadily throughout his entire adult life. In resolution #28, Edwards promised himself that he was “Resolved, to study the Scriptures so steadily, constantly, and frequently, as that I may find, and plainly perceive myself to grow in the knowledge of the same.” 1

That same year (1722) while still a teenager, Edwards began a series of personal journals, his “Miscellanies,” which would serve for the rest of his life as his theological and philosophical thinkpad. 2 Bound by hand and stitched together with whatever sources of paper Edwards could harvest, 3 the “Miscellanies” became for Edwards an extended collection of notebooks where he could ponder Scripture, take notes on works both ancient and modern, stretch his intellectual legs, and plot chapters for his great future works. Edwards labeled the first entry “a,” and quickly went through the alphabet twice before wisely moving into a more sustainable numerical system.

In these notebooks, Edwards recorded contemplations both long and short on topics such as holiness, happiness, grace, resurrection, conscience, God’s foreknowledge and more; all dutifully quoting and annotating the Scriptures with his own system of biblical cross-references. 4

The Miscellanies

By the time he graduated from Yale with his master’s degree at age 20, he had already written some 150 entries, and his system of scriptural observations was growing quickly. 5 The benefit of such a system was obvious: Edwards could record his ideas in long-form without page constraints (provided he could obtain usable writing paper), by simply annotating the number of the miscellany in the margin of his Bible, rather than having to pack just a few miniscule words into a half-inch margin, as many students of Scripture attempt to do today.

But as the content of the “Miscellanies” grew more and more theological and philosophical, Edwards decided that he needed a separate series of notebooks for purely exegetical insights. Thus, on a freezing night in January of 1724, Edwards began a new series of notebooks entitled “Notes on Scripture,” in which he only recorded direct observations and interpretive comments on Bible texts, by chapter and verse. 6 Like the “Miscellanies,” he allowed the spark of curiosity and the pursuit of personal inquiry to determine the order and trajectory of his entries, forsaking a strictly canonical model.

In an apparently haphazard system, he leaped around both testaments enthusiastically, cross-referencing his entries to his Bible and his other notebooks. 7 Though this system is a bit frustrating to the modern reader since it appears to jump around the canon randomly, it was the best way for Edwards to build a mechanism for making personal commentary notes without having to worry about running out of room to write in the margins or add pages between existing notebooks.

Throughout the years, Edwards began several other notebooks on various subjects, usually following a familiar system: writing numbered entries in no particular order, allowing himself as much space as necessary to work through his ideas and observations, all the while cross-referencing the notebooks to one another in spiderweb style. 8

In October 1723 he started a series of notebooks on the book of Revelation while looking for signs of the onset of the millennium in current events. 9 In 1728 he began a journal on biblical and natural typology 10 —and then yet another on messianic types in 1744. 11

The Blank Bible

When Edwards received an extraordinary interleaved Bible in 1730 as a gift from his brother-in-law Benjamin Pierpont, Edwards obtained what might be considered his most precious personal possession, and his system of note-taking tools reached its zenith. This large and highly unusual Bible consists of a small, hand-sized King James Version unbound and then stitched back together again within a much larger notebook—one blank sheet between every page of Scripture. 12 Pierpont had formerly owned it, but he gave it over to the more promising Edwards after his own ministry aspirations ran aground on a character- related accusation.

The Blank Bible provided Edwards with the canonical master index and table of contents he had been looking for all along. Though he carefully cataloged and indexed all of his journals in other ways, the Blank Bible became for the young preacher the premiere landing pad for insights and references to all of his prior notebooks—and many other commentaries besides. Though the notebooks could grow to unlimited lengths, by necessity they could not be canonically arranged. In this way, the Blank Bible could serve his system as the perfect balance between abundant writing space and a more sensible ordering and placement of his comments directly opposite the biblical text itself.

In all, Edwards built one of the most complex and richly textured collections of thoughtful insights in the entire colonial era. Though many others such as Cotton Mather had recommended collecting daily thoughts and biblical observations into journals and diaries, few did so with as much aplomb and consistency as Edwards. Fewer still mastered the art of complex informational organization while pursuing the meaning and significance of Holy Scripture with ardor over the course of many decades.

Edwards used these written materials—some devotional, others practical, still others technical or theoretical—for the near-constant production of preached or printed sermons as well as for short, middle, and long-form treatises. Many of his best theological writings, including his magnum opus, the Freedom of the Will, evidence a high literary dependence on his own notebooks. 13 In many cases, Edwards lifted paragraphs and entire sections from his personal notebooks, quoting them nearly verbatim and recontextualizing them into his relentlessly logical treatises for publication and public consideration.

Take note: study like a Puritan

Jonathan Edwards, the colonial divine and famous preacher of “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” was used by God greatly in his own time as well as our own due in large part to his voracious desire to know Scripture. His organizational genius for collating his own thoughts in writing added to his ability to draft sermons and compose larger treatises that still reward profound consideration these many generations later. And while few of us will ever be given the gift of lucid writing and theoretical comprehension like Edwards, it becomes us to imitate his desire to understand Scripture through concerted effort and wise learning strategy.

As I write, I sit just feet from reams of copy machine paper. Edwards would have considered such a stack a treasure trove given that many of his notebooks were handmade from parcel paper, envelopes, and repurposed women’s church fans. Simple black-and-white composition notebooks would have also been treasured joyfully, if not greedily! A digital storage system as powerful as a computer? Unfathomable.

Despite our obvious advantages in the modern age, I have been attempting to imitate some of Edwards’ habits. A couple of years ago, I started my own “Miscellanies” system based on Edwards’ model. I bought a nice journal, skipped a few pages for composing an eventual index, and began with #M001. After that, I wrote #M002 and so on. If one of my miscellaneous observations correlates to a particular Scripture text, I simply annotate the code “M001” in my Bible. I have now written my first 100 miscellanies.

In addition to that, I have begun other notebooks, some digital, others on paper. On my computer, I have a file that I call my “Digital Miscellanies.” Here, I record sermon illustrations, quotes, and anecdotes in alphabetical order, by topic. Unlike paper journals, I am not limited to any particular spatial confines, and I can add searchable entries ad infinitum. I started another digital journal on theological headings, creating my own outline of systematic theology, and still another digital notebook on philosophy.

Though few if any of us have been given the same mental acuity as the famed Northampton revivalist, we can at least share his passion for studying and understanding Holy Scripture. The logical first step on the journey is to simply “resolve” to begin.

***

This article was originally published in the July/August 2022 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related articles

- How to Study the Bible: 9 Tips to Get More Out of Your Study

- 3 Bible Study Methods to Jump-Start Your Time in the Word

Related resources

- “Resolutions” in Letters and Personal Wrings, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Volume 16 (New Haven: Yale), 755.

- The “Miscellanies” are contained in WJE 13, 18, 20, and 23.

- WJE 13:69.

- WJE 13:117–120.

- By the end of his life, Edwards would pen over 1,400 entries.

- Notes on Scripture is the subject and content of WJE 15.

- For instance, the first 10 entries in Notes on Scripture comment on the following passages respectively: (1) Genesis 2:10–14, (2) Matthew 13:33, (3) Luke 14:22–23, (4) Matthew 21:40–41, (5) Genesis 6:4, (6) 1 Kings 6, (7) Genesis 22:8, (8) Canticles (Song of Solomon) 8:1, (9) Matthew 3:7, (10) Matthew 9:10.

- See Illustration #1 below, from WJE 10:90.

- This notebook is contained in WJE 8, Apocalyptic Writings.

- This notebook is contained in WJE 11, Typological Writings.

- This, too, is contained in WJE 11.

- A description of the Blank Bible‘s unusual physical form can be found in WJE 24:84–89.

- WJE 1:4–5