Eugene Peterson’s The Message elicits strong feelings on the internet. Quite a number of Christian YouTubers, for example, have insisted that it is fit only for the flames. When I posted a (basically positive) video about The Message, I soon received impassioned responses from commenters. One actually called it “the worst thing there is about modern evangelicalism”; another called it simply “heresy.”

I can’t honestly say that I spend lots of time reading The Message. I’ve never read the entire thing. But when I do turn to Bible paraphrases, it’s the one I use, and I’m very glad it’s there. Why does the internet wish it dead?

I’m about to praise The Message and demonstrate its value, so I get to start this article by mentioning a criticism that I think will help explain some of the confusion and negative feelings swirling around Peterson’s work. It’s this: The Message is a paraphrase, not a Bible translation. You could get the opposite impression if you read the preface. The Message basically calls itself “a Bible”—a “reading Bible.” It doesn’t call itself a paraphrase except at one obscure point in its introduction to the Psalms. But that’s what it is.

Because it’s a paraphrase, I cannot recommend that The Message be used as a church’s preaching Bible or as your lifelong “main” Bible from which you memorize and in which you study. No, I’ll argue briefly in this piece that while The Message contains some Bible and can help you see the Bible in a new light, it’s a paraphrase and not a Bible.

Rather than putting down The Message by saying this, I insist that I am doing it a favor. You can’t know what The Message is good for until you know it’s a paraphrase.

Bible paraphrases

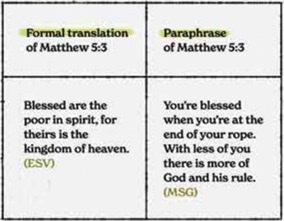

What is a paraphrase? It’s a transcultural rewording of a text. It’s a mama bird chewing up some Bible food and spitting it out in a more palatable form to the baby birds. It’s taking the words of the Bible and doing this to them:

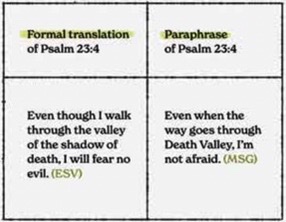

Here’s another example, because you learn paraphrase by looking at it:

The Message isn’t the only Bible paraphrase. Kenneth Taylor’s The Living Bible, first published in 1971, is probably the other best-known and most-used paraphrase among English-speaking Christians. I’ll focus, however, on The Message—and lessons we learn about it will apply to other paraphrases.

That’s because every major Bible paraphrase does the same thing to the Bible that you see in the two examples above. They use familiar words and imagery from our time and place to try to explain the Bible. They do a little translating, a little commentating, and a little transculturating.

Peterson is not trying to improve on Jesus. He isn’t saying that Jesus should have said “at the end of your rope” instead of “poor in Spirit.” But for those who’ve heard the famous phrase “poor in Spirit” their entire lives, it can be very helpful to hear Peterson’s transposition of that phrase. It’s so, so easy to let famous and common phrases come to mean nothing through repetition. A paraphrase provides a shock to the system; it’s a horse that (be patient with my metaphor here) strains at its traces and yanks the wagon it’s pulling out of a deep rut.

And I need this—don’t you need this? I just want to understand my Bible. The best thing I can say about a paraphrase is that it helps me understand God’s words.

“The Valley of the Shadow of Death” is a meaningful phrase to me—but I’ve never seen such a valley on TV. I have seen California’s Death Valley. It has physical, tangible existence in this American life of mine; it is a resonant cultural image. Seeing David’s death valley through the lens of my own is helpful.

Who is it good for?

For me. Helpful for me. I’ve never felt more like saying, “WARNING: THIS BIBLE STUDY PRODUCT MAY NOT BE HELPFUL FOR YOU.” If you’re a beginning Bible student, don’t start with The Message just because it goes down so easy, like sugar. If you’re a beginner and your Bible-reading skills are shaky (and you humbly know it), grab the New International Version, a translation on the border between formal and functional. If that’s too hard, grab the New Living Translation, a more consistently functional translation. But if your reading skills are good, I suggest you start with the formal translations (ESV, NASB, NKJV, LEB) and build up your knowledge and skill before you grab functional ones and paraphrases. You have to wear a rut in your mind before you can be helpfully yanked out of it.

I think The Message is, ironically, an intermediate or advanced Bible study tool and not a beginner one. It’s like what I often say at church, where I lead singing: one of your goals in Bible reading should be to get to the point where you are catching all the allusions to the Bible that fill our hymns. Likewise, you should get to the point where you read Romans 3 in The Message and know—just know—the original melody off of which Eugene Peterson is riffing:

But if our wrongdoing only underlines and confirms God’s rightdoing, shouldn’t we be commended for helping out? Since our bad words don’t even make a dent in his good words, isn’t it wrong of God to back us to the wall and hold us to our word? These questions come up. The answer to such questions is no, a most emphatic No! How else would things ever get straightened out if God didn’t do the straightening? (Rom 3:5–6ish MSG)

“Wrongdoing” is “unrighteousness”; “rightdoing” is a didactic neologism (a word Peterson made up for teaching purposes) for “righteousness.” “Straightened out” is Peterson’s paraphrase of the word “judge.” These three courtroom words (“unrighteousness,” “righteousness,” and “judge”) are massively important in Paul, and by paraphrasing them Peterson is diminishing the connections good readers might make between this passage and others where Paul employs the same concepts.

But Peterson is also shining light on these concepts from new angles by using highly contemporary language. The word “righteousness” carries musty religious overtones; “rightdoing” doesn’t. The verb “judge” is mainly negative in our culture; Peterson can help remind us that God’s judgment will be welcome to his saints: it will involve the “straightening out” of a crooked, fallen world (see Rev 6:10).

Often when I’m using some Bible study tool, I think, Only the Bible is worth this kind of attention. So much commentary and scholarship and preaching and songwriting, and on and on, have been generated by and about the Bible. Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase is simply another such tool.

Answering objections to paraphrase

A pastor friend of mine recently wrote a paraphrase of a Bible passage and read it out loud to his congregation. Some people were incensed. It felt to them like he was messing with Scripture. But he graciously and firmly defended himself, and I think he was exactly right. He said, I do this all the time in sermons. I read a Bible phrase and then I put it in my own words in order to help you understand it better. What’s so bad about doing this for an entire chapter?

Right! Or an entire Bible!

As long as we understand what a paraphrase is, we can make use of it without confusion. A paraphrase—by definition—lets some pieces of information in the original text recede and brings others to the fore. And if we know this—if we know that this is the whole point—we shouldn’t be upset when we see some important bit of meaning “lost” and another “added.”

The best answer to objections may be the pudding-and-eating proof. Just show people what a paraphrase can do. In my experience, people who love and revere God’s word come to love any tool that can help them understand and use and obey that word. I’m convinced that a Bible paraphrase ought to (come to) be in your Bible study toolkit.

***

This article was originally published in the March/April 2021 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related articles

- The Best Bible Translations: All You Need to Know & How to Choose

- Bible Translations: Wisdom in Choosing the Right One

- Should Bible Translations Be Literally Accurate?

Related resources