I constantly compare Bible translations during Bible study and exegesis. But not everyone sees the value in this practice, and some are outright skeptical: they think I’m inviting confusion, a he-said, she-said method of exegesis. Or they think it’s too much work for too little profit. All I know is that over and over again, comparing translations has been helpful to me as I seek to understand the Bible. I can’t come up with a list of astounding examples off the top of my head; the help I get is often subtle—though it adds up.

The best thing I know to do is invite the skeptics to drink the water I find so refreshing. And the best place I know to experience the value of comparing Bible translation is in Logos’s Text Comparison tool (its Multiview Resources function is equally good though made with slightly different exegetical purposes in mind).

Text Comparison allows you to type in abbreviations, separated by commas, for all the Bible translations you want. My text comparison needs change depending on my exegetical situation: sometimes I want a set of translations for the New Testament, so I use SBLGNT, ESV, AV, NASB95, NIV, NET, HCSB, NLT.

Sometimes, of course, I’m in the Old Testament, so I change SBLGNT to BHS or LHB. Sometimes I want just two Greek texts (I like to compare Scrivener’s TR to the NA28, for example).

You can type out very quickly the abbreviations for the versions you want to see, and the pop-up window below will make suggestions for you if you need any help:

But if you’re like me, there are a few standard sets of translations you like to compare. A set for the NT and a set for the OT like I mentioned—and a set for foreign languages, a set for LXX study, or maybe for comparing the critical text of the NT with the Majority Text. Now in Logos the Text Comparison tool saves your five most recent sets, and that may be all you need. You can toggle back and forth among the five you use most commonly.

Bonus tip

There is an ongoing argument about New Testament textual criticism in the Christian church, and not just among scholars (or among the King James Only crowd). There are serious, scholarly Majority Text advocates of various shades such as Maurice Robinson who don’t hold to the critical text(s) most biblical scholars today use.

Those arguments are important. I’m glad there’s a minority report on textual criticism; it’s healthy for the overall science. And I think Robinson in particular makes some telling points. And there are Christian people outside of the academic biblical studies community—people in the pew—who have followed these arguments.

But I also think there is great danger that debate over textual criticism can get overheated, precisely because the details are extremely complicated, not to mention written in ancient Greek. What are the actual differences between the major Greek texts on offer? How significant are they? You can’t know first-hand unless you read Greek. And even if you do, it’s pretty laborious to compare Greek texts.

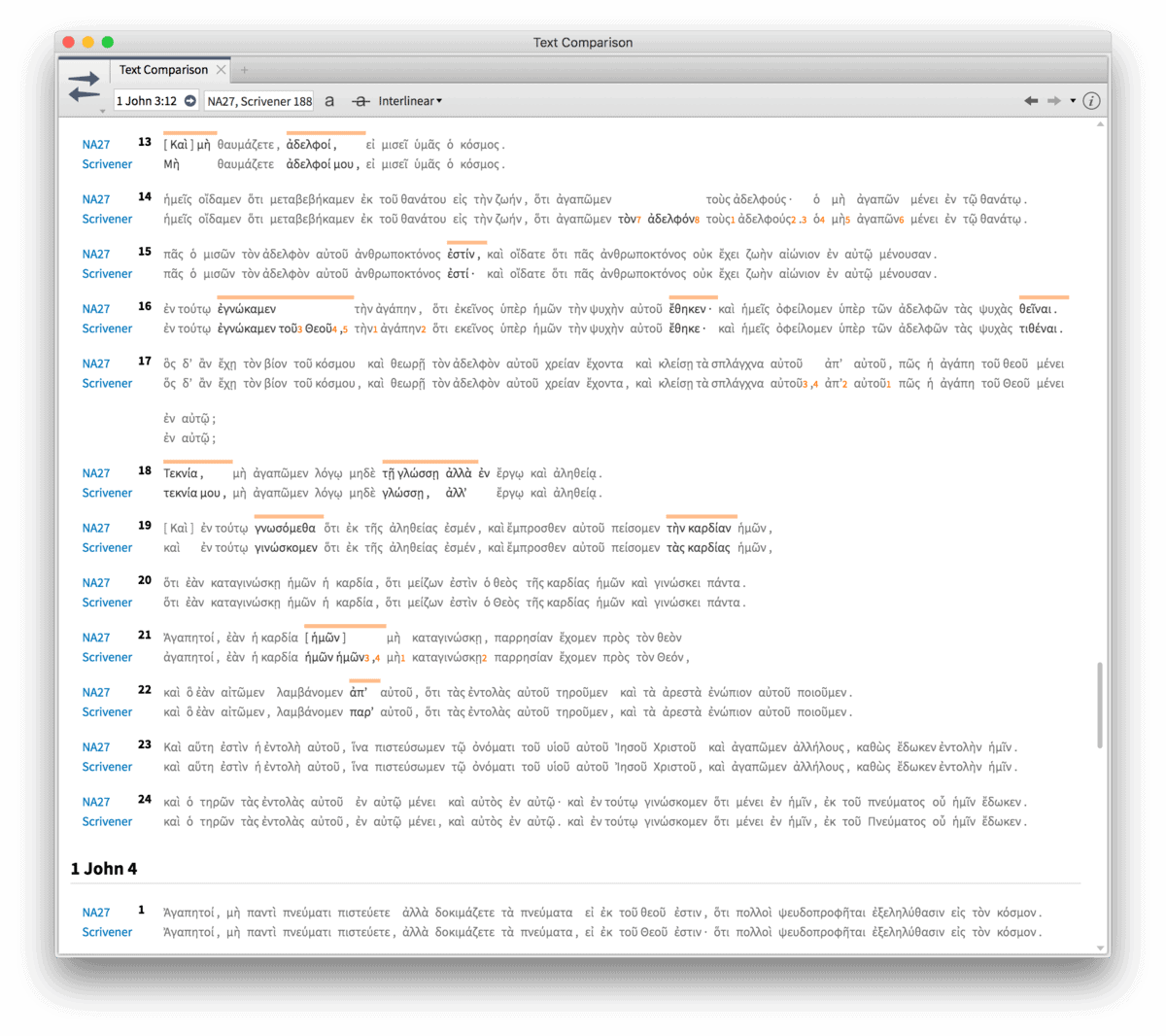

Unless you have the Text Comparison tool. Put it in interlinear mode, compare the Nestle Aland (critical) text with Scrivener’s 1881 Textus Receptus (the basically Majority text underlying the KJV), and you can quickly spot differences. Significant ones are marked with orange bars:

Concluding advice

My advice is to consider carefully what five sets of translations you want in your recent sets. The NA27/TR comparison I just demonstrated may or may not be useful for your particular needs, but here are a few other sets you might consider:

- All Romance language translations you own. You can often piece together what a Spanish, Italian, or French translation is saying if you ask it a narrow question—like “Is ἀτακτως (ataktos) in 2 Thess. 3:14 best translated ‘unruly’ or ‘idle’?” (I have sometimes used German and other languages, too—anything that uses the Roman alphabet.)

- All ancient language versions you own, such as the LXX, Vulgate, or Syriac—plus English translations of those.

- All English language Bibles you own—in case you want to check every single last one of them for a plebiscite on the rendering of one particular statement.

- All literal or all dynamic translations you own.

- All the English translations and original language texts you actually use on a day-to-day basis.

Set up those sets one at a time and they’ll be in your recents list for good.

Mark L. Ward, Jr. received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the church as a Logos Pro. He is the author of multiple high school Bible textbooks, including Biblical Worldview: Creation, Fall, Redemption.