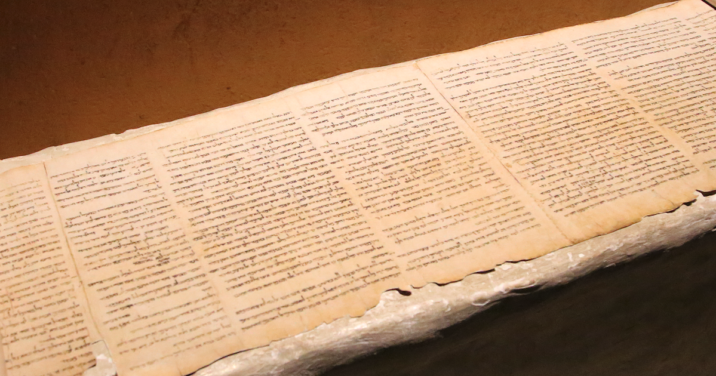

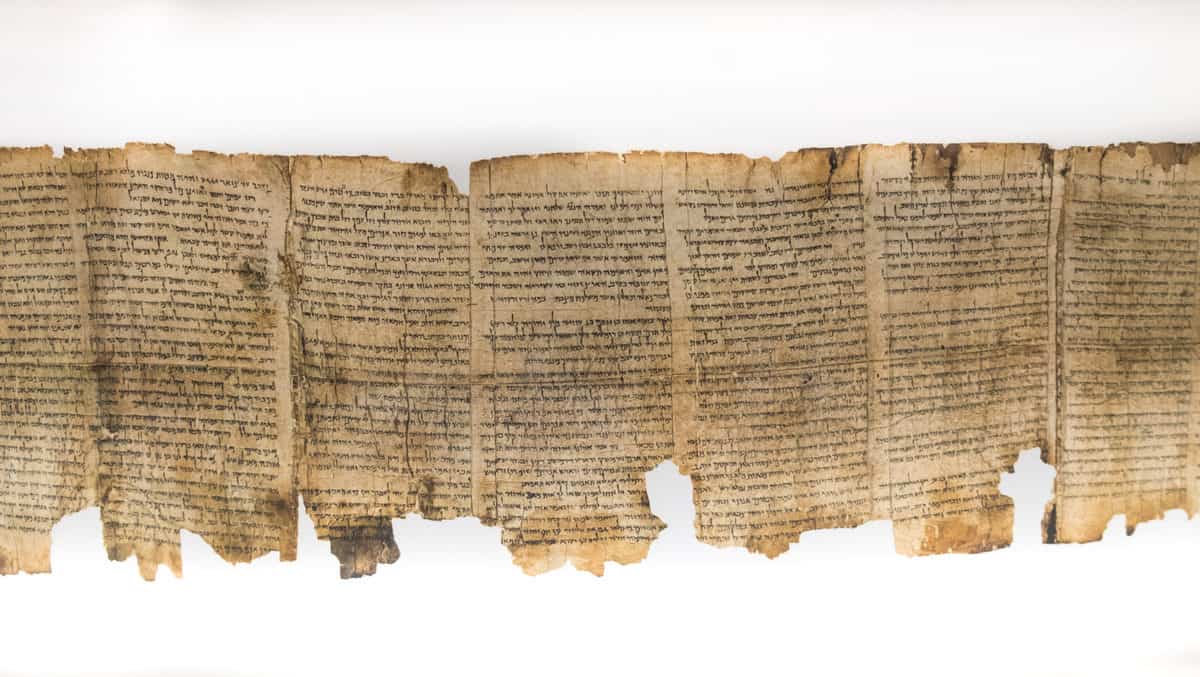

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, depending on how you count it. (The January-February issue of Bible Study Magazine tells the story of their discovery if you’re not familiar with it—it’s worth the read.)

Many people know a little about the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), but fewer people understand just how revolutionary the scrolls have been to our modern study of the New Testament. In the below excerpt, Drew Longacre, a specialist in the Hebrew and Greek texts and manuscripts of the Old Testament at the Qumran Institute of the University of Groningen, considers three ways the Dead Sea Scrolls impact our study of the New Testament—and why it matters.

***

Most Christians are familiar with the basic storyline: a man of priestly lineage, a retreat to the desert for a lifestyle of asceticism, an emphasis on baptism and repentance, an apocalyptic message, a voice crying in the wilderness: “Prepare the way of the Lord!”

If you think I’m describing John the Baptist, you might be surprised to learn that I’m actually talking about the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) found at Qumran. While there is no clear evidence that John, Jesus, or the early Christians ever visited Qumran or interacted with its inhabitants, the parallels above demonstrate the importance of the DSS for understanding the New Testament (NT). The study of the DSS has revolutionized the study of the NT by providing context and background directly from ancient sources.

Texts and interpretation

In addition to familiar OT texts, the DSS also revealed a wealth of literature that is not often known by modern Bible readers. Some scholars initially (and mistakenly) supposed that they had found copies of some NT writings at Qumran, but it now seems clear that no Christian writings were found in these caves. A few of the books of the Apocrypha were found, like Ecclesiasticus (aka Ben Sira), Tobit, and the Epistle of Jeremiah. But many of the discovered works were either completely unknown or only known in very late translations. Some reflect the teachings of a relatively small group that many scholars think could be the Essenes, but many of the texts clearly circulated more broadly in literate Jewish circles of the period and were highly regarded. Some of them are even cited or alluded to in the NT, such as the quotation from Enoch in Jude 14–15. Thus, the DSS provide important insight into the kinds of non-canonical texts that the NT authors would likely have been familiar with and sometimes even influenced by

The DSS also offer insight into the ways the Old Testament was interpreted by Jewish readers in NT times. There were three main ways texts were interpreted in new compositions:

- First, biblical stories were often selectively retold with interpretive additions, a practice that has similarities to how the writers of the Synoptic Gospels are generally supposed to have built upon each other’s work.

- Second, the Qumran scrolls have several examples of writings—mostly on the prophetic books and Psalms—that provide running commentary on Scripture passages, a form of literature that does not occur in the NT.

- And third, authors in both the DSS and NT sometimes explicitly cited biblical texts in support of their arguments, demonstrating a shared respect for the authority of the Scriptures. Several DSS (e.g., 4Q175) simply excerpted significant or thematically related passages of Scripture in a pattern that may help explain why different NT authors often cited the same OT verses.

Both the DSS and NT have several significant tendencies in common when citing the OT. For one, the books of the Pentateuch (Genesis–Deuteronomy), Isaiah, and Psalms were apparently as popular in Qumran as they were in the New Testament. Both the DSS and NT authors also show an interesting tendency to interpret OT texts in light of their own situations, expanding the meaning of the OT texts beyond their original intention. From this perspective, the Psalms and prophets were speaking not just about past times but also about the contemporary experiences of the nascent church or the community associated with Qumran.

Thus, the NT relates the voice crying in the wilderness in Isaiah 40:3 to John the Baptist, while the DSS relate it to the community in the Judean Desert. OT texts were not just about the historical past but also about eschatological realities. The DSS demonstrate that this manner of interpretation was not strange or particular to the NT authors but was a widely accepted hermeneutical practice at the time.

Language and literacy

The DSS also provide important documentation for the languages that were spoken and written in Judea in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Aramaic was the official language of the Persian administration, so Aramaic came to be widely spoken and written from the fifth-century BC onward. Aramaic was commonly used for legal documents throughout the period. Also, many of the early non-canonical Jewish literary texts were written in Aramaic, and sometimes scribal mistakes in Hebrew copies of the Scriptures reveal that their scribes were primarily experienced in Aramaic. By the time of Jesus, there is little doubt that Aramaic was the most common mother tongue among Judean Jews.

Nevertheless, most of the DSS were written in Hebrew, which shows that Hebrew never completely died out as a language of the Jews in Judea. There are a few examples of letters and legal documents in Hebrew, and it is even possible that some Jews continued to speak Hebrew as their first language in Jesus’ time. But Hebrew certainly continued to be used, especially for religious texts and prayer.

After the conquest of Alexander the Great, Greek also became increasingly common throughout the Mediterranean, including in Judea. Some Greek compositions and copies of Greek translations of the Hebrew Scriptures were found in the caves of the Judean Desert, along with many legal documents written in Greek. Numerous inscriptions from around the turn of the era and later also demonstrate the significant influx of Greek, especially among the upper classes. As the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean, Greek was the natural language of communication for NT authors concerned with the international spread of their message.

It is impossible to determine ancient literacy rates precisely. Certainly, the large majority of Judean Jews could not be considered literate by modern standards, and few would have been able to comfortably read diffcult literary texts. But it is clear that, by the time of Jesus, reading and writing was not limited to elite, professional scribes. Signatures on legal documents suggest that many could at least write their own names. Others could write personal or administrative letters, and well-educated individuals could be quite competent in composing their own literary texts. Judean society at large can probably be considered literate only in the sense that crucial social functions like law and religion depended upon written texts and that there were enough literate individuals to fulfill those necessary functions, even if the majority of people could not and did not need to.

Ideas and practices

The DSS also give firsthand insight into some of the ideas and practices that were current around the time of Jesus. Earlier generations of scholars had been largely reliant on recollections of uncertain historical accuracy culled from later rabbinic literature for information on this important period. Many ideas evident in the DSS have parallels in the NT, such as strict deterministic dualism between the righteous and the unrighteous, identification of the community as the righteous remnant within Israel, an emphasis on baptism and repentance, messianism, apocalypticism, and eschatological expectation. Sometimes there are even specific verbal parallels, such as the references to the “works of the law” in the halakhic letter 4QMMT and Paul’s letters.

This is not to say that the authors of the DSS always—or perhaps even often—agreed with the early Christians. For one, they were very much concerned with strict legal interpretations. In a commentary on the book of Nahum (4Q169), the author calls his opponents “the seekers of the smooth things (ḥalaqot),” which may be a pun on the more lenient legal rulings (halakhot) of the Pharisees. The movement associated with Qumran was also largely priestly both in origin and leadership, strongly hierarchical, and strictly regulated, in sharp contrast with the early Jesus movement. Furthermore, the spread of early Christianity with the incorporation of believing gentiles differs greatly from the perspectives of the authors of the DSS.

The DSS have thus provided crucial background for the study of the NT. They give primary documentary evidence for the types of languages, texts, interpretations, ideas, and practices that were familiar to the NT authors, which helps modern scholars situate the NT authors in their historical contexts and sheds important light on the NT texts.

***

Read more articles about the Dead Sea Scrolls in the January–February issue of Bible Study Magazine, including how to study the DSS using Logos, the effect of the DSS on our English Bible translations, and more.

Related articles

- Study the Dead Sea Scrolls

- What the Dead Sea Scrolls Can Teach Us about the Annunciation

- This Recent Dead Sea Scrolls Discovery May Impact Septuagint Studies

- Do the Dead Sea Scrolls Answer the Canon Question?

- The Profound Implications of the New Dead Sea Scrolls Discovery

Related resources