In this article, I argue that we have been too apt to accept ancient and popular interpretations of Jesus’ wilderness testing in Matthew 4:1-11. Three issues warrant a fresh interpretation: the translation of πειρασθῆναι, our understanding of Satan’s role in the narrative, and the relationship between the two “sons” of God, Jesus and Adam.

πειρασθῆναι Presents a Theological Problem

The term πειρασθῆναι is defined in Louw Nida as “to endeavor or attempt to cause someone to sin—‘to tempt, to trap, to lead into temptation, temptation.’” However, the problem with translating ancient texts is that the receptor languages, in our case English, are subject to change. Living in a digital age, most of our congregations will simply perform a Google search to define terms, and if you seek to define “temptation” in Google, you will see the gloss, “the desire to do something, especially something wrong or unwise.” And this is problem: where the Greek usage and English usage at the time of Louw-Nida did not include an inner desire to sin, the current English idiom does. Did our Savior feel an inner desire to do something “wrong or unwise,” i.e. sinful? Because of the change in the receptor language, we should probably translate this term as “testing,” where Jesus was being pressured from an outside source to commit a sinful action, but felt no desire to do so. If we say that Jesus felt an inner desire to do any of these three actions, then by Jesus’ own high moral standards, he is guilty of sin. Our well-meaning congregants need to see the connection because too often they have made a direct correlation between this passage and the book of Hebrews to draw a false comfort which was never meant to be understood the way that they have. This brings us to the second issue with our passage.

The Testing of Jesus Is Not about How to Defeat Satan

Sermons on Matthew 4:1-11 often link to Hebrews 4:15 — “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin.” We want to know that Jesus was human, and we make a philosophical mistake in assuming that “to err is human” (see Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism). However, this is theologically mistaken. To err, i.e. to sin, is not human. Humans were created in a state of innocence. Jesus, as the perfect man, was man as man was intended to be: without sin. The same issue plagues this particular verse: πειρασθῆναι is being fallaciously interpreted with a later semantic range that the original term was never meant to uphold. Instead, we should see this example of Christ here in Hebrews 4 as being tested from outside and yet without sin. This gives us a stronger urge and example to desire only the pure life God has for us, and not the sin that the world offers through devilish means.

However, I suggest that this is not the main point of this passage. Instead, through an examination of Jesus and Satan’s conversation, one can see that this passage has nothing to do with “us” as current readers, or even the original audience and their struggles with testing.

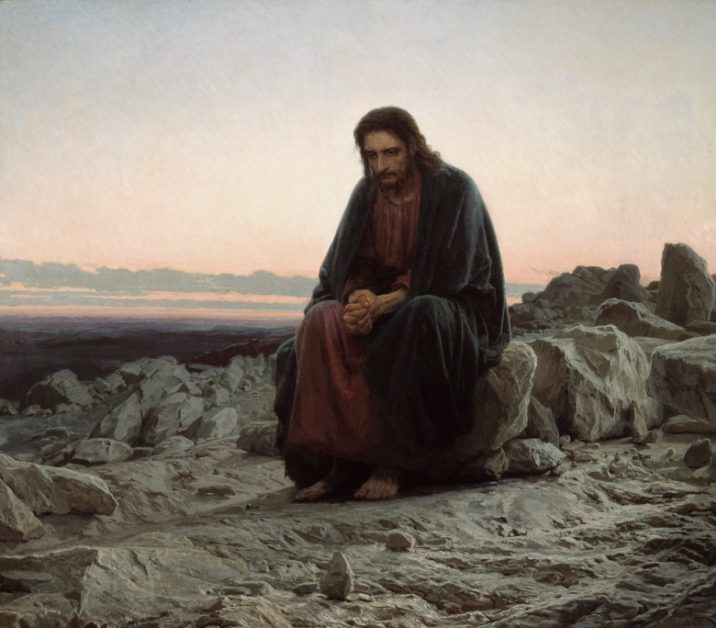

Satan is trying to ascertain whether or not Jesus is the Son of God. This is what the greater context of the passage shows. In Matthew 3:17, God asserts at Christ’s baptism, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.” Immediately Jesus is driven into the wilderness by the Spirit to test this new divine claim, whether or not Jesus is indeed the Son of God. That is why the first two conditionals are challenges to Christ to prove whether or not He is the Son of God, to prove it by taking certain actions. Jesus, however, validates his divine Sonship through his perfect obedience to the Father revealed in the Law of Moses. The third temptation, however, is conspicuous. It shouts at the reader in the original Greek, and for the attentive reader, you can see the issue in English versions as well. Where the first two temptations are offered as first-class conditionals, the third is offered in a third-class conditional, with a subjunctive verb, and the use of ἐὰν. The third test also is offered backward, starting with the apodosis, and ending with the protasis. For English readers, the “then” statement is offered before the “if” of the conditional. With Jesus’ status as the Son of God proven, Satan now seeks to test the quality of Jesus’ divine Sonship. And that brings us to the last interpretive issue the temptation narrative.

Jesus Is the Son of God Who Succeeded where Adam, the first Son, Failed

In the third and final temptation in Matthew 4, Satan wants to know whether or not Jesus is willing to take his divine inheritance early. Jesus does not debate whether or not Satan is able to deliver the kingdoms of the world into his hands. However, the Scriptures show us (particularly in Psalms 2 and 8) that this is the inheritance of God’s Son and divine king. What Satan is offering is to receive this inheritance early, without going through the suffering and rejection that Jesus will experience over his three-year ministry. Jesus refuses and proves to be the faithful Son of God, who perfectly obeys the Father, and waits for his Father’s timing for his own exaltation. This is in direct contrast to Adam, the first Son of God (in human terms, see Luke 3:38) who refused to wait for God to reveal more and more to him, and took the fruit to eat of it so that he might be like God. Instead of seeking to understand Christ in light of the failures of the first generation, we should seek to understand Christ as the greater Son of God who overcame the testing of Satan in his willingness to wait on his Father’s vindication.

Conclusion

After a brief analysis of some issues in Matthew 4:1-11, we can see a few important takeaways. The first idea is that continued proficiency in translation is a necessity, especially in light of the constant evolution in receptor languages, which requires us to question if our previous translations are still relevant. In the case of Matthew 4:1-11, our previous understanding can be setting up believers for unorthodox ideas. The second idea we should walk away with is the need to observe syntactic constructions. If we overlook Satan’s conditionals, in light of the context of Matthew 3, we will too easily miss the point of “if you [Jesus] are the Son of God.” Lastly, we see the need to continue to pay attention to the historical context and to apply it consistently. Honor-shame culture is a deep pool, and it can be difficult to navigate. However, the hard part of inheritance practices has been well documented in other Gospel accounts, and it is our job to make all of the other applications that are fitting. These three ideas are basic hermeneutical principles: translate effectively, observe syntactic relationships, maintain an eye on historical context. By practicing these trusted biblical study methods, we can come to a better understanding of the impeccable obedience of our Lord, which made him capable of being our sacrifice for sins.