We’ve had a few significant posts on the Dead Sea Scrolls on the blog in the last few weeks, including Craig Evans’s breaking news of the discovery of Cave 12, and then a follow-up post that asked the question of the importance of studying the scrolls at all.

In this post, I have two objectives: first, I’m going to introduce you to two of the best ways to study the DSS; second, I’ll show you how to use these resources by looking at two brief examples.

The Two Best Resources

First and foremost, the best way to the study the DSS is with the best resources. One option is travelling to Israel to view the scrolls in person. While feasible for some scholars (maybe even required for some research), this option is highly impractical for most of us.

However, there are better and more efficient ways to do your research in this golden age of technology, including high-resolution digital photography and powerful software programs.

A High-Res Picture is Worth…

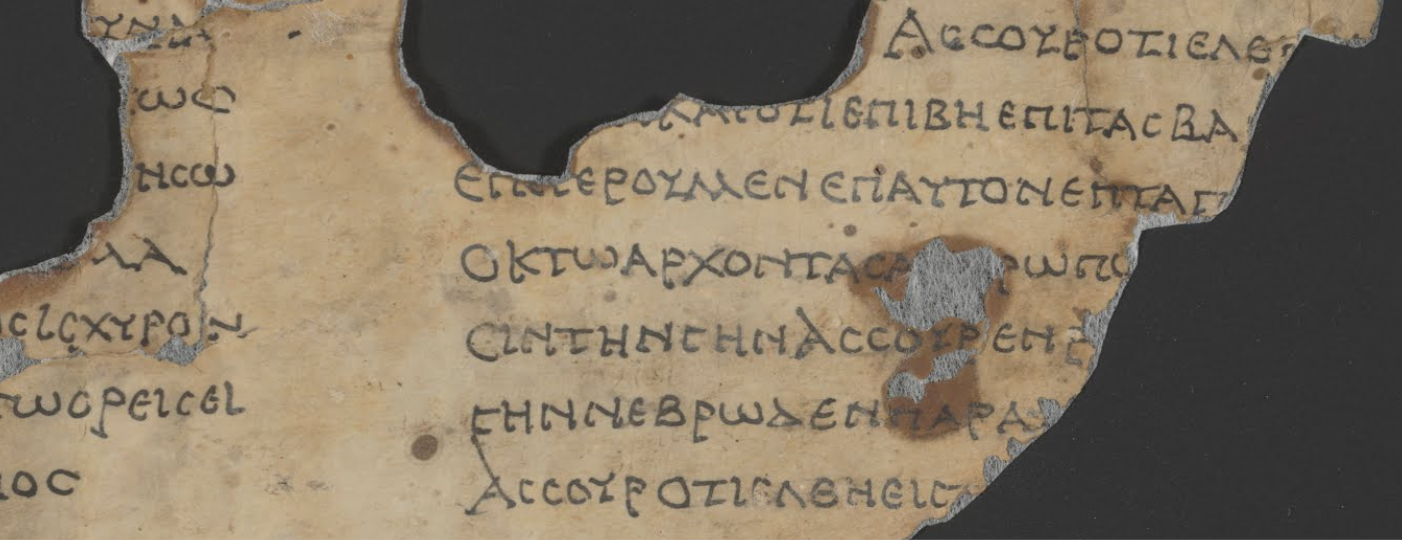

- Undoubtably, the best way to study the DSS is to read them for yourself. The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library is a free, online resource where advanced imaging technology allows for detailed examination of thousands of DSS scroll fragments. These include 4Q Genesis, 11Q Psalms, and 4Q Serekh ha-Yahad, or the Community Rule, among others.

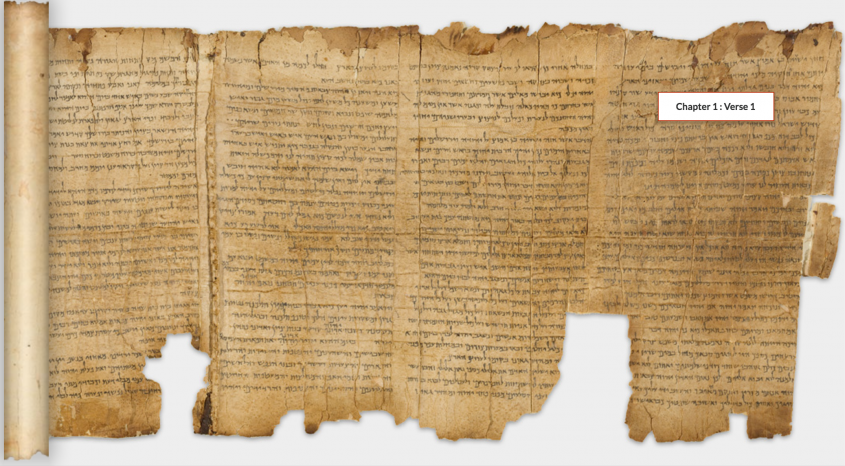

- The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls – Another excellent way to examine the DSS manuscripts is provided by the Israel Museum in the Digital DSS Project. Here, you can view high-resolution images of the Great Isaiah Scroll (with translation!), the Temple Scroll, the War Scroll, the Community Rule Scroll, and the Commentary on Habakkuk Scroll.

As incredible as this access to the original manuscripts might be, we need a partner resource to maximize our research potential. That comes in the form of bible software.

Technology that works hard

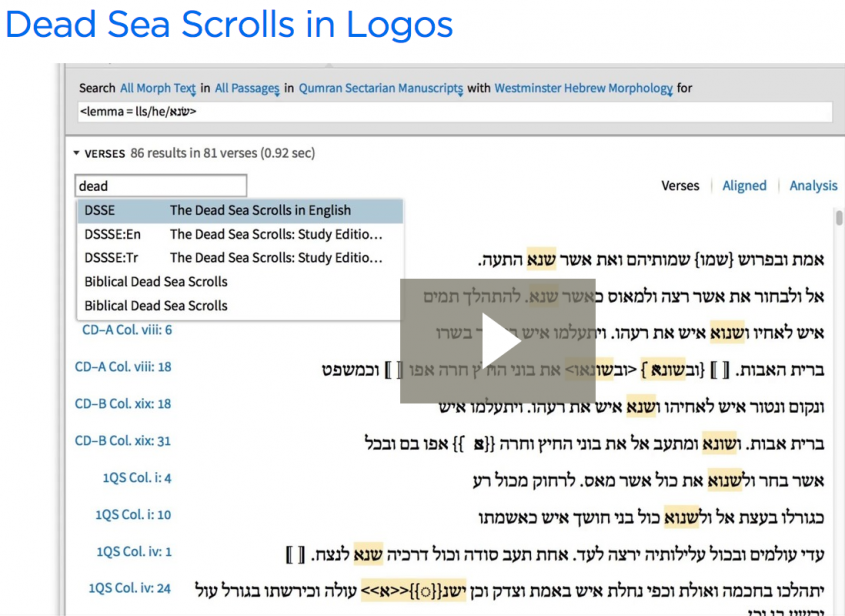

The advantage of using a Bible app like Logos to study the DSS is the immediate accessibility one has to a vast array of tools, resources, and images, all in one comprehensive package. In Logos, you can arrange your workflow to keep images, translations, commentaries and more both front-and-center and tracking together. Logos enables a level of efficiency that is truly incredible, and a depth of research potential that borders on astounding.

In fact, Logos has provided a number of key entry points to begin or further your study of the DSS. First, this video by the Logos Pro Team demonstrates how to use Logos to effectively utilize DSS resources in a study of Matthew 5:43:

Second, Craig Evans has an excellent course on Matthew in its Jewish Context that incorporates the DSS extensively to identify Jewish elements in the Gospel.

Two Examples, Big and Small

Here is where things get fun; we get to use these resources now in actual Bible study. I’m going to mention two brief examples of how the DSS can enrich your study of the biblical text. The first example is more of a big picture approach, where the DSS provide helpful background to the world in which the NT writers lived. The second example is a bit more specialized, where we examine an issue of textual criticism using the DSS to help our interpretive decision making.

Comparing theologies of “grace”

If we are to grasp the historical significance of Jesus’ appearance in ancient Palestine, we must learn the historical landscape. And part of that learning process requires becoming familiar with the people, culture, and places which made up the complex tapestry that Jesus and the NT writers inherited.

The best way to do this is through a combination of dictionary articles and specialized monographs that deal specifically with the topic at hand, all of which are readily available on Logos. Once you’ve mastered the general topic of the DSS, you’re ready to approach the biblical text, namely the NT, and start making fruitful comparisons.

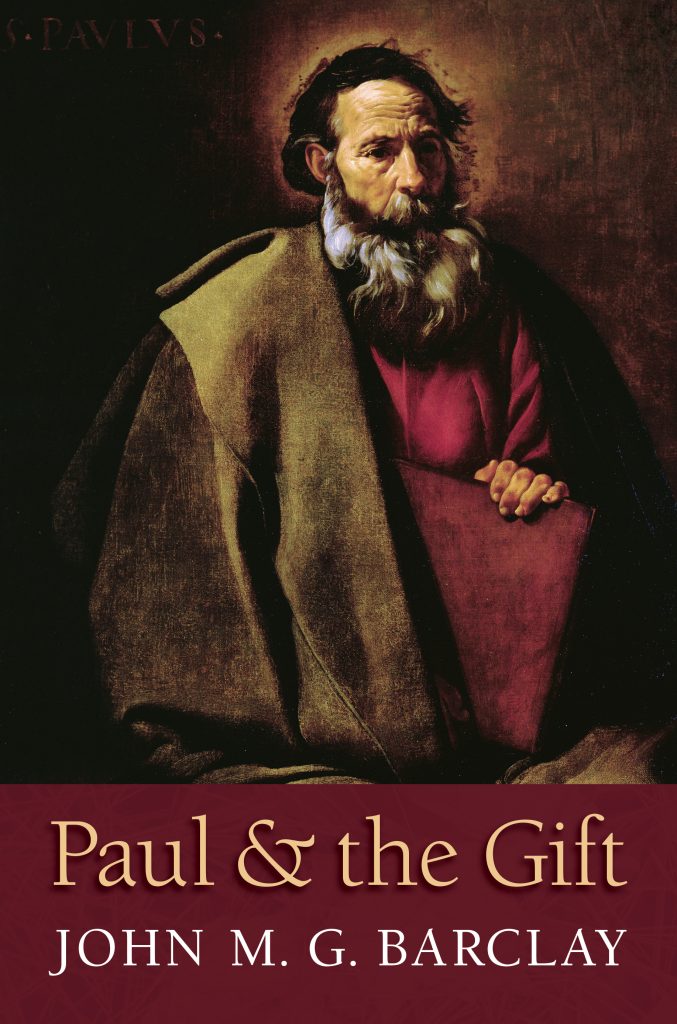

As I mentioned in the previous post, John Barclay has recently discussed Qumran in an exceptional study of the concept of χάρις in Second Temple Judaism, which includes Paul’s letters to the Galatians and the Romans. Barclay focuses on one DSS text in particular, the Qumran Hodayot (1QHa), otherwise known as the Thanksgiving Hymns.

Barclay articulates the significance of the Hodayot, in that they “represent another striking articulation of divine benevolence, with the distinctive accents of a sectarian community.”1

In other words, they are a tremendous resource if one wants an example of another community, like the early Christian church, that saw themselves as distinct from other similar groups and completely dependent upon the mercy of God for their very existence.

One example in the Hodayot that Barclay highlights is from 1QHa XIX.6-17:

I thank you, O my God, that you have acted wonderfully with dust, and with a creature of clay you have worked so very powerfully.

Barclay follows this citation with a fascinating section on the ubiquitous language of self-deprecation that peppers the Hodayot.2 In support of this understanding of the Qumran community, he cites the following statement from 1QHa XX.27-34:3

As for me, from dust [you] took [me, and from clay] I was [sh]aped as a source of pollution and shameful dishonor, a heap of dust and thing kneaded [with water, a council of magg]ots, a dwelling of darkness. And there is a return to dust for the creature of clay at the time of [your] anger [ ] dust returns to that from which it was taken. What can dust and ashes reply [concerning your judgment? And ho]w can it understand its [d]eeds? How can it stand before the one who reproves it?… There is none who can reply to your rebuke. For you are just, and there is none corresponding to you.

This type of language is of course evident also in Paul. Here are two passages that make a great comparison with 1QHa:

- Romans 9:21 – Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for honorable use and another for dishonorable use? What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory— even us whom he has called, not from the Jews only but also from the Gentiles?

- 2 Corinthians 4:7 – But we have this treasure in jars of clay, to show that the surpassing power belongs to God and not to us. We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies.

However, the difference with Paul’s use of the “dust” or “clay” metaphor is that, while initially remarking upon the unworthiness of humanity, he ends with strong statements affirming the value of people redeemed by God:

- In Romans, God’s sovereignty is on display as he chooses vessels according to what will bring him the most glory.

- In 2 Corinthians, the brittle jars of clay are contrasted with the God of power, who sustains his people in order to display the life found in Christ.

Thus, although human beings are completely unworthy in their unredeemed state, God grants them his incongruous grace to make them valuable beyond estimation, in as much as they are vessels for his glory.

The Hodayot are similar, in that they affirm the mercy of God. The sectarian’s value lies only in being a child of God according to God’s electing choice.4

There is much more that could be said about the benefit of this type of comparative work between the NT and the DSS. But I hope that pointing you to Barclay’s work (check out his outstanding bibliography on the DSS) will motivate you to press further into this type of study.

At this point, we can say that the DSS show us that Paul wasn’t the only Jew in the first century who thought of God’s grace as being given to completely unworthy recipients. Paul’s theology shared elements with his Jewish peers, even if the main point of disjunction was the reality of Christ’s death and resurrection.

The DSS show us both the similarities and differences between the many branches of Jewish thought active in Early Judaism. We can and should use the best resources at hand to compare and contrast these systems of theological inquiry in order to know the NT better, as well as the DSS.

Matthew’s fulfillment quotations

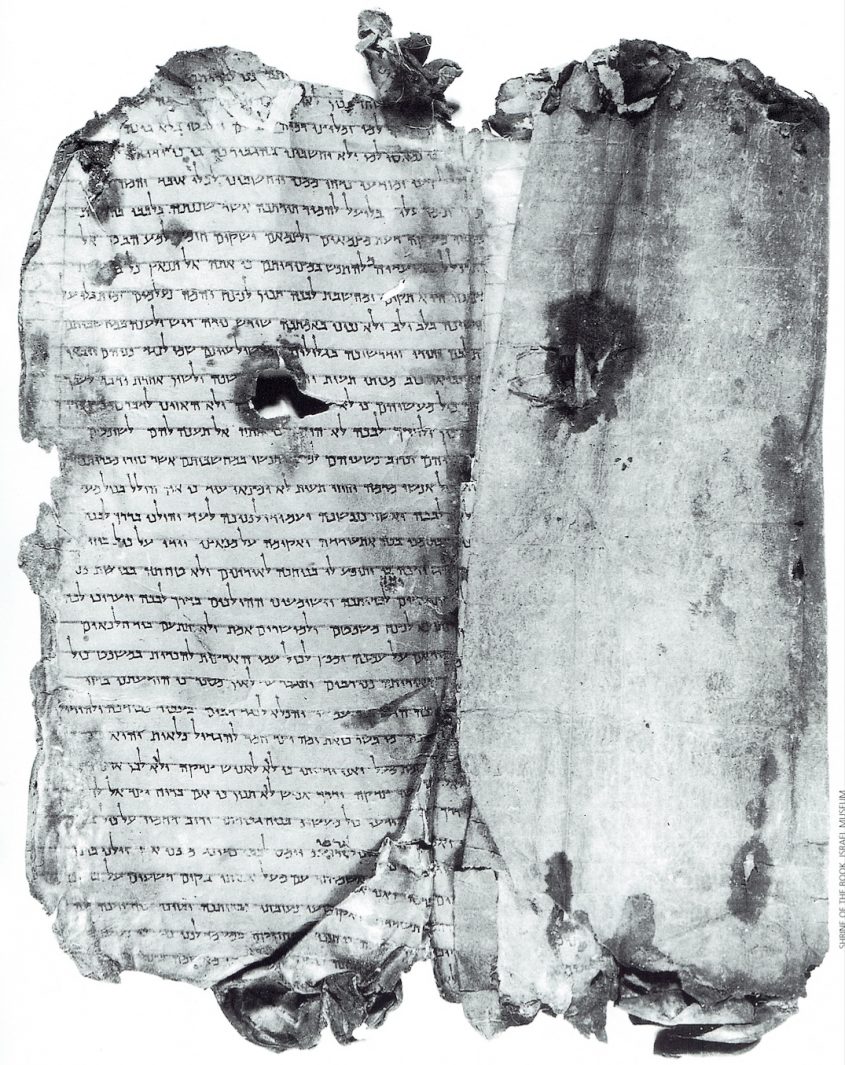

While our first example was from the so-called “sectarian” manuscripts from Qumran, we turn now to look at some biblical texts, specifically Isaiah.

The DSS are a vibrant witness to the essential character of the Old Testament writings in ancient times. They serve as one example of the various attitudes to the written text of Scripture. They often transmit the biblical text differently than other sources, including the Masoretic Text (MT), the LXX and the NT authors.

Thus the DSS are helpful in making important decisions in the area of textual criticism, especially when a NT author is citing from the OT. A good example of this is the so-called “fulfillment quotations” in the Gospel of Matthew.

Unique to Matthew is the use of 11 fulfillment quotations, in which the author cites from Isaiah (6), Zechariah (2), Jeremiah (1), Hosea (1), and the Psalms (1).5

These quotations, mostly from Isaiah, are intended to portray Jesus as the long-awaiting fulfillment of various OT prophecies.

A good case study is the citation of Isaiah 7:14 found in the infancy narrative of Matthew 1:18–25. There Matthew writes,

All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet: “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Immanuel” (which means, God with us). (Matthew 1:23)

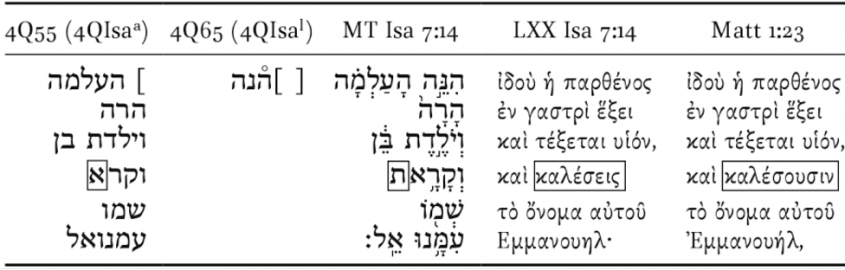

There is an important textual issue here. Matthew has changed the person and number of the verb καλέω (“to call”) compared to the possible source texts, either Hebrew or Greek. In Matthew, we find the 3rd person plural, καλέσουσιν (“they shall call”); the Hebrew (MT) uses the 3rd person singular, וְקָרָ֥את (“she shall call”); and the LXX uses the 2nd person singular καλέσεις (“you shall call”). So we have a problem; Matthew seems to have changed the original text, no matter which one we think he used.

But what about the DSS? Will it lend support to Matthew’s alteration? Gert Steyn compares Matthew with the LXX and MT, as well as 4QIsaa and 4QIsal, in the following chart:6

What we find is that both the DSS and the Masoretic Text (MT) disagree with Matthew’s 3rd person plural; every other witness besides Matthew, from the LXX, DSS, MT and otherwise, have the singular reading of “to call.”

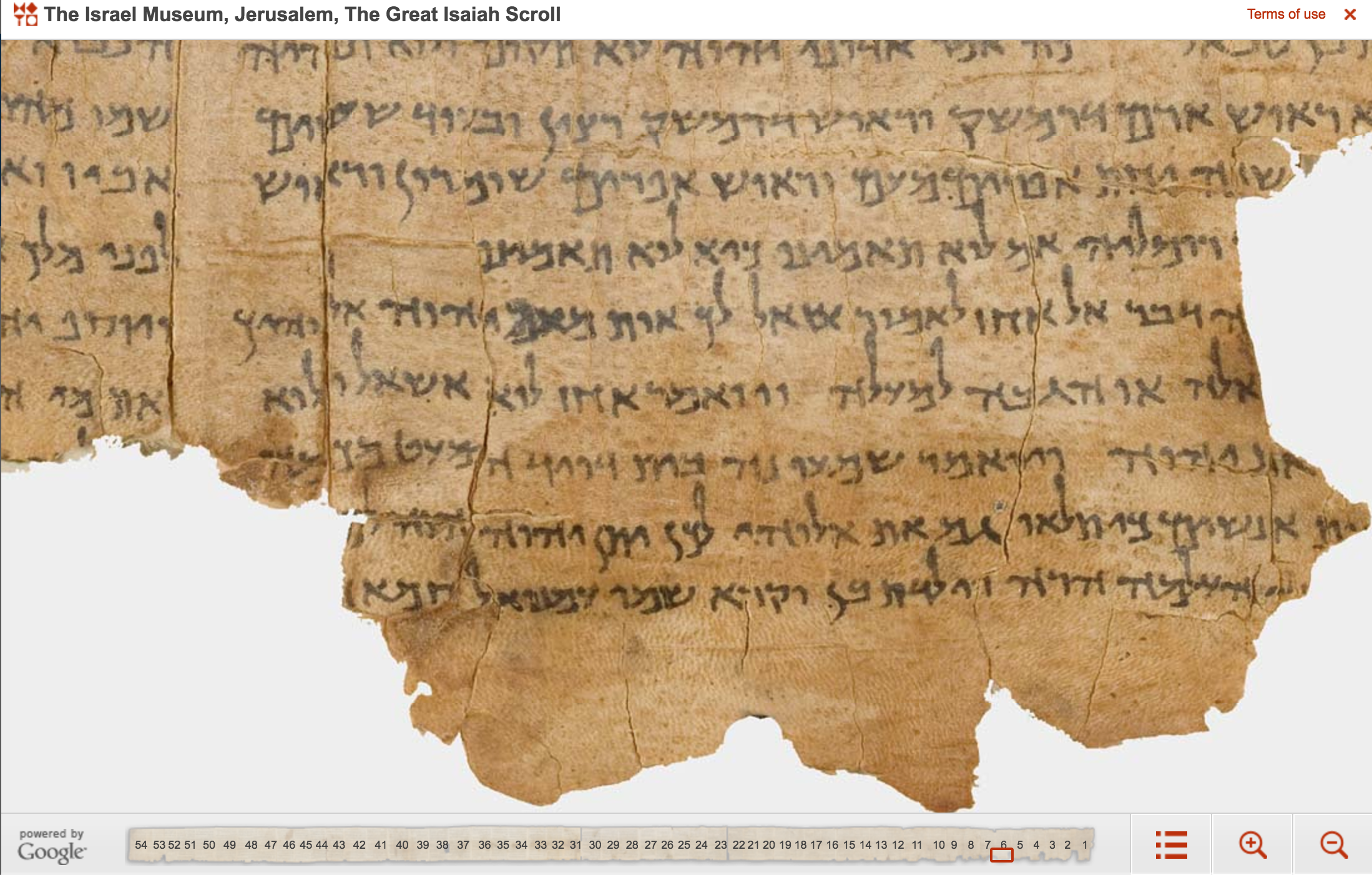

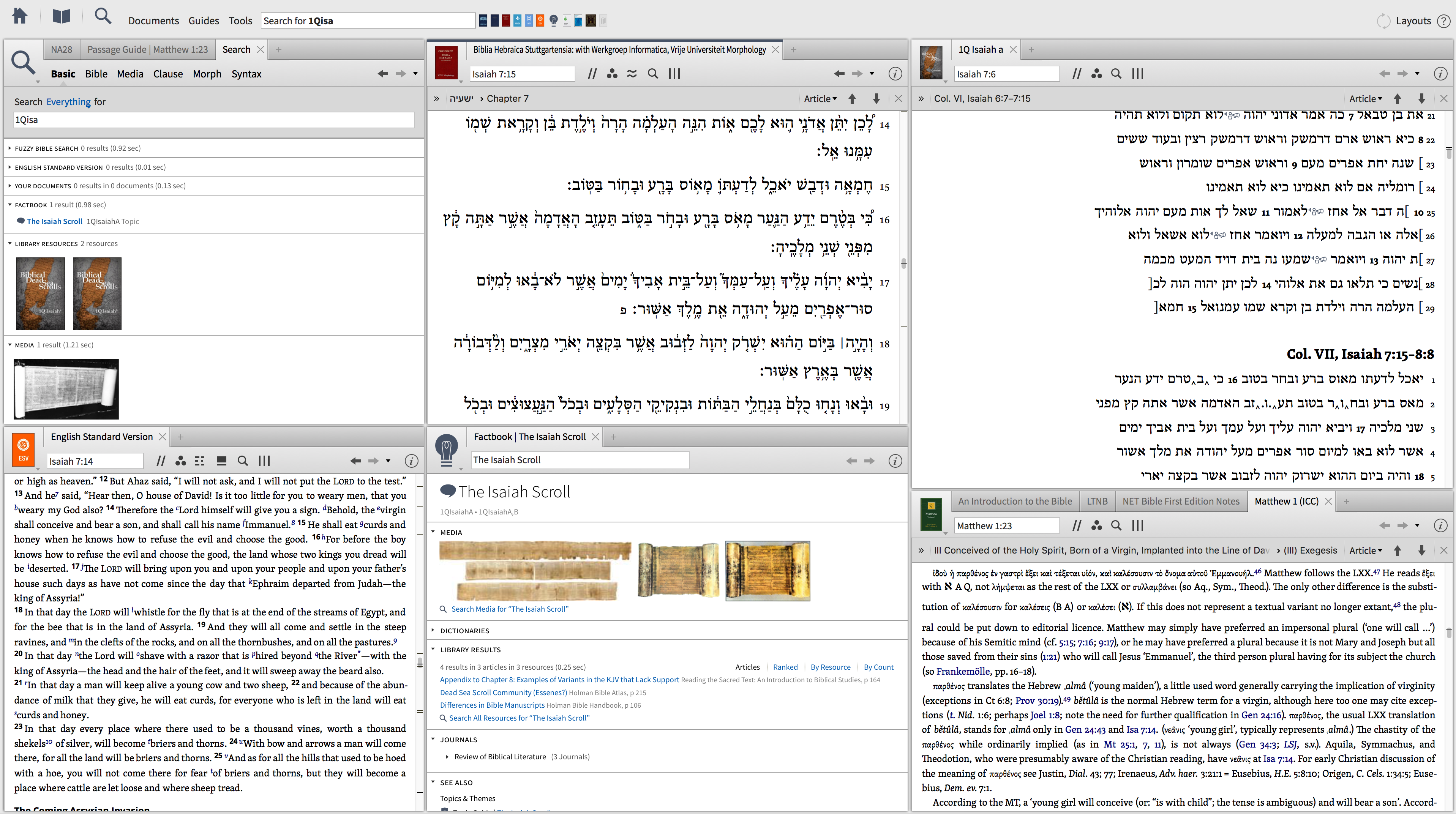

We can verify these findings in two steps. First, we can quickly access the high-resolution images discussed in the first part of this article. The image below is a screenshot from the Israel Museum of the Great Isaiah Scroll; the bottom line is Isaiah 7:14, and the word right in the middle is וקרא, the exact verb we are discussing, with the 3rd person singular ending in clear view (note the prominent aleph):

This layout enables me to view clear transcriptions of 1QIsa, read my BHS alongside it, access hundreds of resources discussing The Isaiah Scroll, and even view media of the scroll itself. More to the point, we can see plainly in our Logos display that our verb in the Isaiah Scroll is also singular, not plural as in Matthew.

In light of this evidence against an original plural ending in the DSS or the MT, Steyn concludes that “[o]ne can assume with fair certainty that at least the plural of the 3rd person, as found in Matthew’s version, is due to his own hand.”7 This verdict seems sound given the evidence that we’ve been able to corroborate through our viewing of the actual manuscripts and our use of Logos 7.

But what can we say about Matthew’s reworked citation of Isaiah 7:14 from the standpoint of interpretation? What are we to make of the fact that Matthew has “changed” holy scripture? Davies and Allison’s ICC commentary on Matthew offers us some help here (visible in the Logos layout above; see the lower right-hand corner).

Matthew’s alteration, according to Davies and Allison, is perhaps due to “editorial license.” Matthew may very well be trying to communicate the fact that “all those saved from their sins … will call Jesus ‘Emmanuel’; thus, the 3rd person plural indicates the church.8

If this is the case, then our study of Matthew 1:23 in comparison with the DSS, along with the LXX and MT, has been extremely helpful. We have been alerted to the striking creativity of Matthew as an author and editor of scripture. If the DSS had agreed with Matthew, the change in number for the verb form would be less significant.

Matthew seems to have changed his source citation because he was directly addressing his contemporary audience. He applied Isaiah’s words directly to the New Covenant community, the church, through a simple change from the singular to the plural. To paraphrase, we might say that Matthew intended his audience to hear Isaiah 7:14 this way:

All the redeemed church will call Jesus, “God with us.”

And that’s exactly what the ancient church did, and what the church does to this day.

A good time to start

There couldn’t be a better motivation to study the DSS than the recent discovery of a 12th Qumran cave. As more revelations from Cave 12 (and soon others?) make their way to light of day, scholars, pastors, and students will need to know what the DSS are, why they are important, and how best to study them.

I’ve identified the resources listed above as the “best” because they enable you to work with the actual (digital) parchments in the original languages. Introductions and monographs are also important, but you should first begin by working within the actual text itself. Then, as we did in our examples, move on to specialized works to make fruitful comparisons with the MT, LXX, and NT.

I hope you find these resources and examples helpful as you begin, or continue, your foray into the compelling texts of Qumran. If you know of other websites or programs that might be useful, please be sure to share them in the comments section below.

- John M. G. Barclay, Paul and the Gift (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015) 239.

- Ibid., 245-51.

- Ibid., 246.

- Ibid., 251.

- Gert J. Steyn, “The Text Form of the Isaiah Quotations,” in Text-critical and Hermeneutical Studies in the Septuagint, edited by Johann Cook and Hermann-Josef Stipp (Leiden: Brill, 2012) 429n10.

- Ibid., 431.

- Ibid., 432.

- Davies, W. D., and Dale C. Allison Jr., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew (vol. 1; International Critical Commentary; London; New York: T&T Clark, 2004) 213-14.