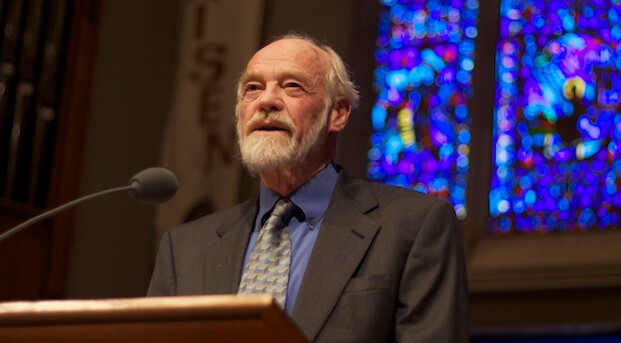

Pastor and author Eugene Peterson entered paradise this morning.

Peterson was a Presbyterian pastor for most of his adult life, though he’s best known for his writings—particularly The Message, a contemporary rendering of the entire Bible.

I was late to the game on Peterson. It only occurred to me a few years ago that he was the author of The Message, which years before I had regarded as a loosey-goosey handling of God’s Word.

That was before I read his memoir, The Pastor.

In it, I learned that the project came from a simple desire for members of his congregation to understand the Book around which their life was to revolve. (I also learned that the biblical imagination behind it came from years of careful original language study—before Peterson was a pastor, he earned a PhD in Semitic languages.)

Peterson discerned this congregational need from intense listening, a commitment I’d like to reflect on in his honor.

Peterson’s turning point

In The Pastor, Peterson describes a turning point early in his pastoral ministry that would shape how he pastored for the rest of his life.

His young church was growing rapidly and demanding much of his time, and Peterson could not keep pace. He writes:

One evening after supper, Karen—she was five years old at the time—asked me to read her a story. I said, “I’m sorry, Karen, but I have a meeting tonight.”

“This is the twenty-seventh night in a row you have had a meeting.” She had been keeping track, counting.

The meeting I had to go to was with the church’s elders, the ruling body of the congregation. In the seven-minute walk to the church on the way to the meeting, I made a decision. If succeeding as a pastor meant failing as a parent, I was already a failed pastor. I would resign that very night.

We met in my study. I convened the meeting and scrapped the agenda. I told what Karen had said twenty minutes earlier in our living room. And I resigned. I told them I had tried not to work so hard, but that I didn’t seem able to do it. “And it’s not just Karen. It’s you too. I haven’t been a pastor to this congregation for six months. I pray in fits and starts. I feel like I’m in a hurry all the time. When I visit or have lunch with you, I’m not listening to you; I am thinking of ways I can get the momentum going again. My sermons are thrown together. I don’t want to live like this, either with you or with my family.”

“So what do you want to do?” This was Craig [an elder] speaking. His father had been a pastor. He knew some of this from the inside.

“I want to be a pastor who prays. I want to be reflective and responsive and relaxed in the presence of God so that I can be reflective and responsive and relaxed in your presence. I can’t do that on the run. It takes a lot of time. I started out doing that with you, but now I feel too crowded.

“I want to be a pastor who reads and studies. This culture in which we live squeezes all the God sense out of us. I want to be observant and informed enough to help this congregation understand what we are up against, the temptation of the devil to get us thinking we can all be our own gods. This is subtle stuff. It demands some detachment and perspective. I can’t do this just by trying harder.

“I want to be a pastor who has the time to be with you in leisurely, unhurried conversations so that I can understand and be a companion with you as you grow in Christ—your doubts and your difficulties, your desires and your delights. I can’t do that when I am running scared.

“I want to be a pastor who leads you in worship, a pastor who brings you before God in receptive obedience, a pastor who preaches sermons that make scripture accessible and present and alive, a pastor who is able to give you a language and imagination that restores in you a sense of dignity as a Christian in your homes and workplaces and gets rid of these debilitating images of being a ‘mere’ layperson.

“I want to have time to read a story to Karen.

“I want to be an unbusy pastor.”*

Peterson was describing the pastor he wanted to be. Looking back, we read it as the pastor he was—to hundreds in person and thousands in print.

Peterson was a listener

That night, Peterson was asking to slow down enough to listen—to listen to God, to listen to the community, to listen to his family.

He understood that to do what he had been called to do, or rather, to be who was called to be—and who the congregation needed him to be—he needed quiet to hear God and others.

Years later, Peterson would voice these same themes in The Contemplative Pastor:

Pastoral listening requires unhurried leisure, even if it’s only for five minutes. Leisure is a quality of spirit, not a quantity of time. Only in that ambiance of leisure do persons know they are listened to with absolute seriousness, treated with dignity and importance. Speaking to people does not have the same personal intensity as listening to them. The question I put to myself is not “How many people have you spoken to about Christ this week?” but “How many people have you listened to in Christ this week?” The number of persons listened to must necessarily be less than the number spoken to. Listening to a story always takes more time than delivering a message, so I must discard my compulsion to count, to compile the statistics that will justify my existence. (30)

Peterson’s insights were won through listening, as all worthy insights are. For him, much of being a pastor meant being a chief listener, awake to the work of God in every detail of life, alive to every word of God in Scripture. He was a doctor with one finger on the pulse of his congregation, the other on God’s Word, listening, listening, listening, and only then speaking.

This is why his writing moves us.

Peterson for today

The Karen story and The Contemplative Pastor long preceded the technology boom that has made life even more hurried. Attention is in short supply; the contemplative pastor is a dying breed.

This is why we must keep reading Peterson and anyone who inspires us to listen—most of all Jesus.

Hear Jesus’ words to a busy Martha in the Gospel of Luke. In Peterson’s words:

As they continued their travel, Jesus entered a village. A woman by the name of Martha welcomed him and made him feel quite at home. She had a sister, Mary, who sat before the Master, hanging on every word he said. But Martha was pulled away by all she had to do in the kitchen. Later, she stepped in, interrupting them. “Master, don’t you care that my sister has abandoned the kitchen to me? Tell her to lend me a hand.”

The Master said, “Martha, dear Martha, you’re fussing far too much and getting yourself worked up over nothing. One thing only is essential, and Mary has chosen it—it’s the main course, and won’t be taken from her.” (Luke 10:38–42, MESSAGE)

Peterson is enjoying that main course now and forever, but he didn’t wait for death to taste it. He sought it every day—“hanging on every word he said.”

He listened. And it’s why we listened to him.

***

*Taken from The Pastor (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 277–278.

For more insights from Eugene Peterson, I recommend this conversation between him and Krista Tippet on the On Being podcast.