Beginning at some time in the sixth century, a form of commentary manuscripts known as catenae were introduced into the exegetical world of the Byzantine Empire. A catena differs from the standard, single-author commentary by being comprised of short, edited extracts taken from various patristic authors and strung together in the form of a “chain” (catena in Latin) commentary. These multi-author commentaries are believed to have begun with Procopius of Gaza, who produced a catena on the Octateuch.

Catenae on the New Testament are believed to have begun at a similar date, in the late-sixth or early seventh century, beginning with the Gospels and followed thereafter by the Pauline and Catholic epistles. These “chains” of patristic extracts in some manuscripts surround the biblical text along the upper, outer, and lower margins of the folio in a frame format while others adopt an alternating format aesthetically similar to single-author commentary manuscripts. Scholia are often identified with names or sigla representing the source, among whom are Origen, John Chrysostom, Severian of Gabala, Severus of Antioch, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, Oecumenius, and, for the purposes of this discussion, Photius of Constantinople.

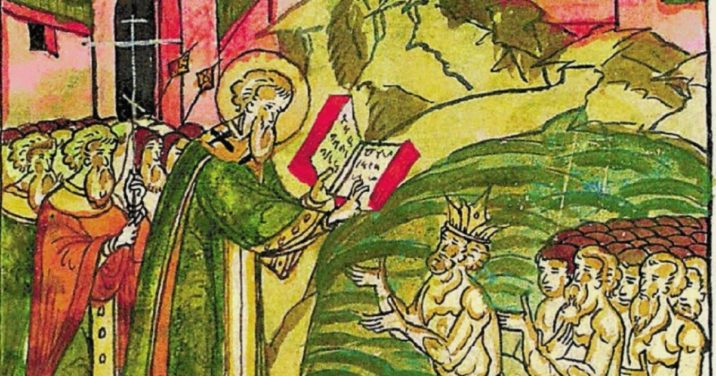

Photius I, Patriarch of Constantinople

While many, if not all, of the names present in catenae will be known to readers, the work and life of Photius is likely less popular. Photius was patriarch of Constantinople (858–866 and 877–886 CE) and a dominant figure in Byzantine religious, social, and political life in the ninth century. Prior to his installation as patriarch, Photius also served as the head of the University of Constantinople. He is most noted for his works, The Bibliotecha—which summarizes and provides his personal thoughts on 280 classical works, many of which are now lost—and the Amphilochia—a theological treatise of the Christian faith formatted into three hundred questions and answers.

The extracts associated with Photius in the catenae are generally marked with a siglum consisting of a τ with an elongated vertical bar which intersects with a φ and an ω at the base. He is also the latest (dated) commentator to be added to the standard collection of patristic authors. His inclusion into catena manuscripts comes at one of the latest stages of evolution for manuscripts and is somewhat of a mystery given that they are included at a time when independent exegesis was discouraged and nothing was to be added to the voices of the divine fathers—a promulgation set down at the Council in Trullo in 692 CE. A possible explanation for his inclusion among the fathers is in the preface to the Epanagoge (or Eisagoge), an introduction to the legal code of Basil I of Macedonia. In this introduction, we read that, “The Patriarch alone must interpret the maxims of the ancients, the definitions of the Holy Fathers, and the statutes of the Holy Councils …” The Patriarch in question was Photius. This is an important shift in exegetical practice in the Byzantine Empire, as these writings mark some of the first independent exegeses of Scripture at the time which did not explicitly rely on the teachings of earlier fathers.

How did Photius exegete a text?

While the Amphilochia provides readers and historians with an insight into the theology of Photius, his only surviving direct exegetical work can be found in catenae, primarily in the Pauline epistles.

Allegory versus grammar

When we look at the Photian extracts, two primary observations can be made: the commentary lacks any of the customary allegory found in the Alexandrian fathers, aligning with a more Antiochene exegesis. The patriarch is largely focused on the grammar and syntax of a text, as one would expect from a university professor, and there is a sense that through the grammar proper, exegesis is achieved. Here, I will provide several examples from the Pauline catenae:

In a comment attached to Romans 5:12, the Patriarch employs the question-and-answer format popular in his day and employed in his Amphilochia. He writes,

It says that by this [the blood of Christ] “we will be saved.” In what way? Because this is both possible and reasonable and consistent. Where is this made clear? From its opposite, for it says, “From one man sin entered into the world and through the same, death.” Therefore, if through one man this difficulty came to us, it is possible and follows that from one man, our Lord Jesus Christ, this difficulty is destroyed, and we are given that which is better.

Further on he writes,

“By which all sinned.” Concerning this, it says that we all die together with Adam, and by which we all sin together with Adam. And there, in the beginning, it produced evil. We did not prevent receiving the inclination to evil, but we even cooperated and contrived the ability for great evil.

Photius’s discussion on antitheses as a tool to produce deeper reflection can also be found in the work of John Chrysostom and is fitting of the patriarch’s academic background. However, where Chrysostom explicitly states that what Adam brought to mankind was mortality—not a sin nature as is commonly expressed in Protestant theology—Photius appears to suggest that both death and sin, or at least the propensity to evil, come with Adam’s first transgression.

In a scholion attached to Ephesians 3:1 and 3:8, Photius suggests that the two verses should be read in combination. Many contemporary exegetes would apply the τούτο χάριν of verse 1 as pointing back to what is found in the closing verse of chapter 2. Regarding verse 1, Photius differentiates between the punishment that befalls Paul and that which befalls the Ephesians:

For he is a prisoner of Christ, which is to say that he has been bound and punished for the same unchanging faith, but this is not the case for the Gentiles, which is to say that they were punished on account of teaching and preaching to the nations, making many witnesses … but Paul was punished for both Christ and the Gentiles.

Then at verse 8, the Patriarch returns to the τούτο χάριν of verse 1:

“For this reason,” means, “to me—less than the least of all the saints—this grace was given, etc.” Now see that having begun the way around in accordance with proper sentence configuration, he side-tracks the correlation, by configuring the parallel with a type of amplification, as both Thucydides and Demosthenes have done in many places. It says, “for this reason: meaning, the reason of God to build us together into a single dwelling place.

The form of argumentation here is entirely dependent on the syntax of the verses, and the willingness to connect them in a manner that few modern exegetes might be inclined to do. It is reflective of Photius’s academic character, and his reference to classical authors follows naturally from what is known of his classical education and apparently extensive library.

Extended treatments

Photian extracts in the catenae also stand apart from all other patristic scholia in that they are considerably longer and more detailed. One such example is his discussion of Hebrews 5:7–8, which can only be summarized here. Photius arranges his analysis of the text in three points:

- What does Paul (the presumed author of Hebrews) mean when he says that Christ “was heard” (εἰσακουσθεὶς) since Christ was, in fact, crucified and died?

- What does “because of his devotion” (ἀπὸ τῆς εὐλαβείας) mean exactly?

- Does “although he was a son” (καίπερ ὢν υἱός) belong to the text before it or after it?

In dealing with the first question, Photius employs two prayers of Jesus from the Gospels:

But concerning the first [question] we say that the entreaty was not of one kind but two of similar sort. The first being the request to be spared from death, the other the begging. For it says in the same [place] with prayer and supplication, “Nevertheless not my will but yours be done.” And John clearly portrays this, saying, “Father, glorify your son with your glory in order that the Son might also glorify you.” The glory is the glory of the cross and death … which is what Paul means here by “he was heard.”

Put simply, Photius responds to the question of how Jesus’s prayers could rightly be understood to have been “heard” given his subsequent death by pointing out that the answer to Jesus’s prayers was the glory of his crucifixion.

Photius then connects the second question to his initial argument regarding Jesus’s prayers:

Christ was heard not by being spared from death but by his devotion, which is to say that his requests transcended the punishment … Wherefore it says, and “by being perfected” through the suffering of the cross and death … he was not raised because of his death but by the power to save him from death … in that whenever you should think on him being crucified and buried you might esteem him as abiding in … the shared desire of the Father that Christ would suffer for the salvation of the world … but this is based on my personal judgement.

The ultimate point for Photius is that Christ’s devotion to the will of the Father, that he should suffer and die for the salvation of the world, is the reason for his “being heard” and his subsequent glory is the answer to those supplications.

Lastly, in addressing the meaning of “although he was a son,” Photius returns to his grammatical emphasis and uses hyperbaton to understand how this phrase would best be explained:

If one considers “although he was a son” as a hyperbaton, then the saying of the divine apostle might be rendered thus: “During his earthly life, although he was a son, requests and supplications, etc.” That is to say that although having the great privilege of Sonship, being able to do all things in self-determined judgement without requests and supplications—as also the Father does, nevertheless, in his earthly life he presented requests and supplications. But it is also possible … to be rendered thus: “He was heard, although he was a son …” and not heard because of the requests, but because of having the same will as the Father … But if you combine those statements successively, the sense of the scripture will be made clear. But what might it signify if it meant, “he learned obedience through the things he suffered”? Is it that he learned to obey the Father from what he suffered …? Rather, the God-man … learned greatness from even the smallest obedience to exalt and save our generation … understood in a certain sense, he learned this through the things he suffered and experienced. Therefore, one might receive this interpretation, but the second option seems to make the most sense to me …

This might appear to be a convoluted and difficult approach to the text, but it is helped by remembering that the text of Scripture at this point in history was only just beginning the use of punctuation that we observe today. Consequently, proper interpretation depended on an accurate understanding of the syntax before all else. What is possibly more surprising for modern readers is the ease with which a tenth-century exegete manipulates the biblical text to suit his interpretive needs.

Conclusion

Photius, while unique in his willingness to independently exegete Scripture, was not unique in his theological or grammatical approach. Though he was more explicit with his desire to connect syntax to theology, the Greek fathers were all steeped in the language of the Bible and understood it as the bedrock from which all orthodoxy, and heresy, sprang forth.

While it might seem strange to Western readers, and while it may lack the soteriological terminology that has become so familiar to the recipients of the Augustinian tradition, this exegesis also comes from the heart and mind of one devoted to rightly dividing the text. It comes from a culture in which Augustine made no impact—for at least a millennium—and thus provides an opportunity to challenge interpretive and theological assumptions that we all carry with us. It also reminds us of the importance of a grammatical approach to the text. Proper exegesis, for Photius and for all others, depends firstly on understanding the words and the meaning derived from the order in which they are presented. What may at first appear tedious is, in reality, the foundation of interpretation.

***

Further resources

Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis

Regular price: $27.99

Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church

Regular price: $39.99

Participatory Biblical Exegesis: A Theology of Biblical Interpretation

Regular price: $15.99

Biblical Interpretation in the Early Church: An Historical Introduction to Patristic Exegesis

Regular price: $17.99