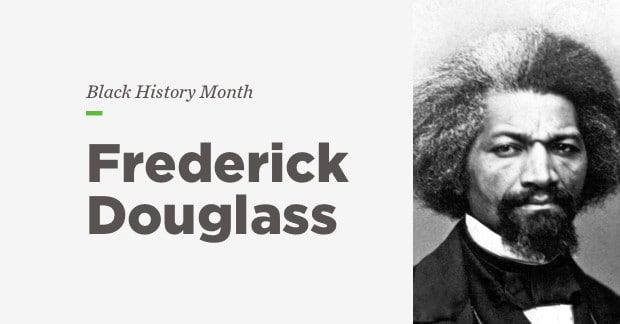

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) fought three great evils in his life: slavery, the subjugation of women, and hatred among humankind.

Born into slavery in 1818 and separated from his mother at birth, Douglass never knew his actual birth date. He was moved around various farms as a child and teenager in New England. He learned the alphabet from one slave owner’s wife, and from there taught himself to read and write—and was soon using the Bible to teach other slaves to read.

Douglass escaped slavery in 1838 and settled in New York City, where he reunited with a childhood friend, Anna Murray. The two were married that same year.

I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do. Share on X

Through various connections, Douglass joined the abolitionist movement as a speaker and leader. By 1847, Douglas began publishing a civil-rights newsletter called the North Star, of which the motto was, “Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren.”1

In his speeches and writings, Douglass hammered at the cruelty and hypocrisy of justice for some, namely the withholding of voting and other rights from women and black Americans. Not only did Douglass work tirelessly for their cause but he also formed alliances across racial and ideological divides. When criticized for this, Douglas responded, “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.”2

That Douglass could engage with slave owners is a testament to his commitment to unity and love in all things. He worked not from a desire for revenge but for justice, not that the wounds of his childhood didn’t leave an indelible mark on him.

They certainly did. Early in his first and most famous of three autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass recounts horrid memories of seeing fellow slaves whipped. He writes:

I remember the first time I ever witnessed this horrible exhibition. I was quite a child, but I well remember it. I never shall forget it whilst I remember anything. It was the first of a long series of such outrages, of which I was doomed to be a witness and a participant. It struck me with awful force. It was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery through which I was about to pass. It was a most terrible spectacle. I wish I could commit to paper the feelings with which I beheld it.

In the following excerpt, which appears alongside these early memories of cruelty, Douglass describes the songs he grew up hearing—and what they meant to him as an adult. His reflections are important for understanding the cruelty of slavery and for correcting a grievous misunderstanding about the songs slaves sang.

(For context, the Great House Farm was a large plantation where select slaves who earned the trust of their masters were granted to run errands.)

***

The slaves selected to go to the Great House Farm, for the monthly allowance for themselves and their fellow-slaves, were peculiarly enthusiastic. While on their way, they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up came out—if not in the word, in the sound—and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. Into all of their songs they would manage to weave something of the Great House Farm. Especially would they do this, when leaving home. They would then sing most exultingly the following words:

I am going away to the Great House Farm!

O, yea! O, yea! O!

This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.

I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension: they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence to these songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conceptions of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds. If any one wishes to be impressed with the soul-killing effects of slavery, let him go to Colonel Lloyd’s plantation, and, on allowance-day, place himself in the deep pine woods, and there let him, in silence, analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul,—and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because “there is no flesh in his obdurate heart.”

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.3

***

For more profiles and excerpts for Black History Month, see:

- Theological Development among African-American Slaves (Video)

- The First Ordained African-American Preacher

- From “Frederick Douglass,” History.com.

- From Wikipedia.

- Taken from chapter 3 of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.