Part 3 of the series Observations from a Linguistic Spectator: An Annual Report. See also Part 1 and Part 2.

From events to verbs

As announced in my last post, I want to explore now in more detail the lexical semantics and the lexicography of Greek verbs. Verbs express events or “situations” as we call them on the most general level. We probably all have an intuitive understanding of what events/situations are: something that happens in the real world at a given point in time. We perceive these events and interpret them and give them a specific shape on a conceptual level.

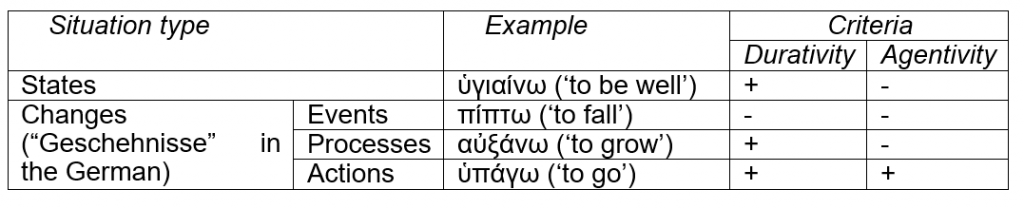

For example, we might say that a lightning strike is a “punctual” situation – even though with specific equipment we can of course also perceive several phases. We use verbs to express these concepts – words such as “to flash.” In other words, “the core semantic function of verbs … is to denote different types of changes …, less frequently states” (AGG 22f). By using criteria such as durativity (“punctual” or not?) we can come up with different classifications of Greek verbs according to their semantics. Here’s a table that I made with the different kinds of situations that Heinrich von Siebenthal adduces, into which I inserted the criteria I believe stand behind these distinctions:

Verb constellations

Note that αὐξάνω can also be used transitively (‘to grow sth.’) – and then it is agentive. This already demonstrates that we need to be more precise and say that when we assign situations to different types, we do so with the mental representations of whole verb constellations, i.e. the verb with its arguments. That means with regard to the verb αὐξάνω that we have to differentiate at least between the two verb constellations [Subject αὐξάνω direct object] and [Subject αὐξάνω] because the concepts they represent belong to different situation types – at least if we use the criteria above.

Aktionsarten and actional potentials

To sum up what we’ve said so far: verb constellations express situations that can be classified into different situation types and that refer to events in the real world. The situation type is also called “Aktionsart” in both German and English literature. The designation is based on the recognition that verbs/verb constellations express different “Aktionsarten,” i.e. different “kinds of action.” (Though in my experience many native speakers are not aware of the – actually quite obvious – etymology.)

It is important that you are aware that in earlier publications – such as BDF – “Aktionsart” was sometimes used for what we now call aspect (cf. also AGG 192c and 194m). Other publications, such as the Cambridge Grammar of Classical Greek, speak of “lexical aspect.” In any case, I strongly recommend that you read Bache’s classical essay “Aspect and Aktionsart: Towards a Semantic Distinction” on the whole matter. I found it very helpful when I started to read more on the issue.

You might wonder why we should even care about classifying verbal concepts in such a way. Of course, we can classify all kinds of things. But what is it good for? After all, isn’t the concrete definition we get in dictionaries all that we need?

Well, in any concrete utterance the verb constellation is expressed with other contextual and grammatical features – such as aspect. And these other parameters – most notably grammatical aspect – can influence the way the situation is portrayed in the end to the reader. Perhaps this is a matter of course for you. However, it’s also possible that you are wondering just how far-reaching this influence specifically of aspect is on the situation that is communicated. We will discuss this in some detail below. For the moment let it suffice to say that the very same verb constellation can appear as significantly different situations – belonging to different situation types – in the different aspects.

It’s also for this very reason that some people speak of “Aktionsart” only with regard to the situation as it is actually communicated and use terms like “Aktionsartpotenzial” or “actional potential” with reference to the bare verb constellation. (That’s also why verb constellations are written in square brackets, to indicate that they are adduced without aspectual and tense values.) Note that in order to know that final product, the thing that is communicated by a speaker/writer, we need to know this input, because grammatical aspect interacts in different ways with different potentials when it comes to situation types that are inherent in verb constellations.

Exegetical significance

As I’ve said, in order to understand what the verb constellation expresses, we need to first know its actional potential – and how aspect interacts with it. It’s difficult to convey just how crucial an awareness of both situation types and grammatical aspect is. Perhaps this consideration helps in making that clear: In order to understand texts, we need to comprehend their propositional structure – and the nucleus of every proposition is usually an “event concept” (AGG 312a).

In other words, this blog post doesn’t address just some highly theoretical linguistic discussions – these issues are rather of the uttermost importance for any responsible interpretation of NT texts. You don’t really know what a text is meant to communicate if you don’t really have an idea about which situations are expressed.

This is also one of the reasons why translating NT texts with students can be so deceptive in my opinion. It conveys the impression that you actually understand what is written, simply because you are able to produce a German or English text on the basis of the Greek. Whether or not the concepts in the target language actually reflect the concepts in the original texts, you can’t really know. The coherence of the translation might give you some indication, but that can lull you into a false sense of security too.

The fact is that if you are not aware of the problem in theory, you might also not notice that something is seriously flawed with your reading in practice. It’s only when you’ve understood the basic parameters that influence the conceptualization of situations conveyed by Greek verbs that you will see the many places where you did not even notice that a potential for misunderstanding was even there. (I’ll adduce a quite telling example from my own work below.)

In fact, even if your translation is correct because you by chance picked words in the target language whose concepts overlap sufficiently with those in the original, this correct translation is not of much use. For you will have nothing but the translation itself, not being equipped with the categories to explicate what is actually being said in either one of the two texts. How are we supposed to imagine the situation? Who is the agent? Whom is he/she/it affecting? How is the scene construed? Where is our attention directed? What is in view and what isn’t? What are we focusing on first, and how is our attention guided? Etc.

If we don’t know that the text comments on these parameters, we will neither be able to comment on them nor be aware of our shortcomings. Perhaps you think I overstate that point. For that reason I want to offer a little test in the next section and I would like to ask you to try to answer it honestly.

A little test

I had always known that aspect was a grammatical category that “has to do with the way the speaker/writer views and presents the ‘action’ of the verb regarding its unfolding in time” (AGG 192c). However, apparently it hadn’t really sunk in because when I read Christopher J. Thomson’s essay “What is Aspect?” in The Greek Verb Revisited it was, I have to admit, eye-opening to me in several respects. I highly encourage you to read that chapter, which the author also uploaded to academia.edu (note that page numbers will refer to the published version). In fact, if you are like I was and you have a deficiency in your understanding of aspect, his article will be much more helpful for you than this post. Note that I will repeat just a few of the insights I gained from that essay, so make sure you read the whole thing.

Here’s what shocked me the most when I read Thomson’s article. In fact, he doesn’t present these observations in this constellation, but what follows is a consideration based on his essay that made the biggest impression me. At one point, he uses the verb constellation [Νῶε κατασκευάζειν κιβωτόν] ([Noah construct an ark]) in Heb 11:7 as an example (pp.55/60). Here’s the question that bothered me: Would the past tenses of both the “present/durative stem” and the “aorist stem” (so my terminology based on AGG 193a) – the imperfect and aorist indicative – form acceptable utterances?

Well, I thought yes. After all, it’s only about different portrayals of the same action. Do you agree? Think about it for a second. If you’ve done so, here’s my next question for you: Imagine Noah had begun the construction of the ark but somehow never finished it. Would both verb forms still be acceptable? Take a second to think about the right answer – and about how sure you are. The first time I asked a colleague about this, he said that he was pretty sure that the ind. aor. would be fine, but not so sure about the imperfect. What’s your take?

Now compare this to the following minimal pair of two English statements, both differing only in aspect: “Bloggs was drowning” and “Bloggs drowned.” Imagine Bloggs struggles to stay on top of the water but ultimately reaches the land. Are both utterances acceptable? Even as a non-native speaker it was immediately clear to me that…

“… there is nothing contradictory about the sentence ‘Bloggs was drowning, but the lifeguard rescued him.’ On the other hand, it would be contradictory to say ‘Bloggs drowned, but the lifeguard rescued him.’”

Thomson, p. 63

Now, I can’t know your answers – but I know how hesitant I would have been to commit myself to a verdict with regard to the Greek that would have been as strong as it was in the case of the English analogy. That’s of course quite embarrassing for someone who had worked with Greek texts for years. Perhaps for some of you this little riddle doesn’t pose any problems at all and you are just amazed at my ignorance. Understandable.

Still, I am quite confident that I am not completely alone in my original uncertainty. For those of you the rest of the post might hold some insights. Also, I think that by now my point about how important this whole nexus of questions is, should have become apparent to everyone. Certainly, you would agree that someone who is not able to differentiate between “Bloggs was drowning” and “Bloggs drowned” appropriately will have a hard time understanding English texts, right? Well, if we are honest, the same applies to Greek …

The markedness of the aorist aspect for boundedness

I thought a lot about why my understanding of the different aspects wasn’t clear enough to make me certain. Here’s how von Siebenthal defines the aorist aspect:

“Speakers/writers typically choose aorist forms when they present the ‘action’/’situation’ as a complete whole (viewed as it were from the outside), as something that is done or takes place without reference to continuation or result.”

AGG 194e

To me, the talk about the dichotomy of a “Binnenperspektive” and an “Außenperspektive” (so the German of AGG 192c, which is now expanded in the English translation) never was really meaningful. What I got was that we need to be careful with statements about the alleged peculiarity of verbs in the aorist, e.g. statements that the aorist “always refers to something necessarily taking place only once” (AGG 194e).

I assume that it is against the background of these kinds of misunderstandings that are very common in German exegetical literature that von Siebenthal stresses how “normal” the aorist is. I know from my own experience how the aorist, due to its strangeness, leads to overinterpretations among students (and sometimes even language teachers). But I also wonder now whether Heinrich von Siebenthal’s understandable concern sometimes leads to problematic formulations, such as in the introduction to AGG 194:

“The aorist is the most frequent of the three aspects in Ancient Greek. For this reason alone it will have to be regarded as the basically inconspicuous or ‘unmarked’ aspect; this also ties in with its use. The durative and the resultative, on the other hand, occur not only much less frequently, but they are usually also more specific regarding the way the speaker/writer may view and present the ‘action’/‘situation’; they are usually more conspicuous or ‘marked’ and thus especially relevant to text interpretation.”

AGG 194

I highly recommend to you the chapter on “Language Universals, Typology, and Markedness” by Daniel Wilson and Michael Aubrey in Linguistics and Biblical Exegesis. It helped me understand my own uncomfortableness with this kind of talk. It’s fine to observe that the aorist (indicative) is apparently the default choice in narrative texts, etc. It’s something different to assume that it is not marked with regard to specific semantic features that need to be taken into account in text interpretation just as the features of the other aspects are in need of consideration. In any case, I noticed that it’s against this background that I ignored other things that von Siebenthal says about the aorist aspect in AGG 192c (again, it’s now a bit expanded in the English version, but the German also was pretty clear as I now recognise):

“[The speaker/writer] may present [the ‘action’ of the verb with reference to its unfolding in time] in its totality, viewed as a complete whole, so to speak, from the outside, without highlighting any of the phases of its unfolding (‘perfective’ aspect). Or they do not present it in its totality, viewed as it were, from within, with certain characteristics of its unfolding such as its progression or continuation being highlighted (‘imperfective’ aspect).”

AGG 192c

In other words: The aorist aspect is marked for boundedness in comparison with the imperfective aspect. Apparently, what was in the forefront of my mind were the statements about the things the aorist did not communicate. AGG 194e even speaks of the aorist indicative as being the “indefinite” tense form – with regard to “continuation and result.” Bornemann-Risch 77, to whom von Siebenthal refers here, say (emphasis mine) that the aspects “kennzeichnen [den Verbinhalt] als etwas Andauerndes oder als etwas im Ergebnis Vorliegendes oder als etwas lediglich (d. h. ohne Rücksicht auf Dauer oder Ergebnis) zum Vollzug Kommendes“ (i.e., that they “characterize [the verb content] as something that is continuing or as something available in the result or as something that merely (i.e. without attention to duration or result) comes to realization”).

Of course, in all these statements, the aorist is compared to the other two aspects. Accordingly, I think it’s most plausible that the terms “Ergebnis” and “result” refer specifically to what the perfect/resultative aspect conveys. All this, of course, is not meant to say that the end-point of a situation (its successful completion, its “result” in some sense) is not included in the portrayal through the aorist.

In other publications, it seems possible to me that the authors assume a truly “unmarked” understanding of the aorist, even when it comes to the inclusion of the boundaries of a situation. Mounce for example (until the 3rd edition) said that the aorist was the “undefined” aspect (with the “action of the verb [being] thought of as a simple event, without commenting on whether or not it is a process”; note that there seems also to be some confusion between Aktionsart and aspect).

As I now realize, the whole point of the metaphor of the perspective from outside (Außenperspektive) is that you see the situation with both beginning and end. Therefore, I really like the way the new Cambridge Grammar of Classical Greek defines the aspect values of present and aorist stems, because they make this very explicit:

“The present stem presents an action as incomplete, focusing on one or more of its intermediate stages, but leaving its boundaries (beginning and end) out of focus. It thus normally signifies that an action is ongoing or repeated. This is called imperfective aspect. The aorist stems (aorist stem, aorist passive stem) present an action as complete, as a single (uninterruptable) whole: it ignores any component parts by looking only at the boundaries of the action, rolling beginning, middle and end into one. This is called perfective aspect.”

CGCG 33.6; I’ve removed any highlighting.

Defining aspect with a view to the temporal structure of situations

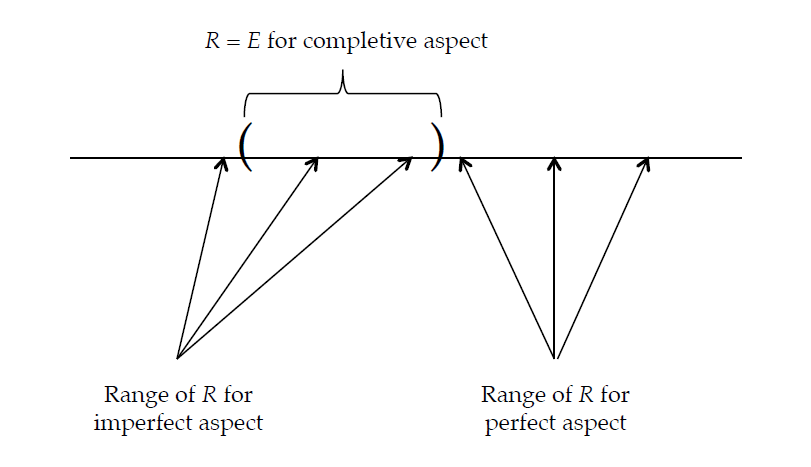

In his own attempt to define the Greek aspects, Thomson builds on the work of the linguists Klein and Johnson. Basically, his argument is that tense has to do with time in that it relates the event/situation time to the speech/orientation time and that aspect is also a temporal category in that it has to do with the internal temporal structure of the situation. More specifically, we can understand the aspects as different relations between the reference/topic time – that is basically the time that the speaker is referring to – and the event/situation time. Here’s a graphic (from p. 37) that illustrates this.

E is the event time, R the reference time. The perfective aspect (here: completive aspect) is defined as R=E. As you can see, the reference time covers the whole event time in this aspect. By contrast, in the imperfective aspect, some part of the event time is after the reference time, i.e. the end point of the situation is excluded from the reference time.

Note that the CGCG goes further by also postulating a part of the event time before reference time. My guess is that these different definitions have to do with whether or not you think there is an “inchoative/ingressive/inceptive” imperfect (cf. AGG 198e). For it to be possible, the beginning of a situation must be included in the reference time so that it can be emphasised.

In the perfect/resultative aspect, the whole event time is located before the reference time, i.e. the speaker talks about a time when the content of the verb has already been realised. (I’ll only address the perfective/imperfective opposition in this essay because the resultative aspect has its own problems.)

Note also that this graphic of course does not include a speaking/orientation time. It’s only in the indicative that the location of the speaker on the horizontal line is specified in relation to the event time. So, for example, both ind. pres. and perf. will usually be embedded into E. (But see part 1 of this series for apparent exceptions!)

Defining aspect in this way is not without controversies either, but it at least helps to avoid a misunderstanding that is so easily possible with the metaphor of looking on the situation “from outside” in the aorist. When we say that you have a bird’s eye view on a parade, that you are looking down on it like from a helicopter (e.g. Mounce), you see the “whole parade” in the sense that you see all the persons, from the first to the last.

What we mean in terms of the aorist aspect, however, is that you see the “whole parade” as a singular event in time, i.e. from its start to its official end. It’s less about your position then about what you do, how much of the parade’s duration you record, for example, sitting there in the helicopter. Do you record the whole thing with your smartphone camera or do you exclude official start and end of the event? (Note that with certain kinds of events, there also seems to be a difference in how close you “zoom in.” “Distance” in that sense might come into play when we have true aspectual opposition, on which see below.)

To be sure, if it’s clear to you that we talk about a temporal structure that is “in view,” you can of course continue to use the metaphor of different perspectives.

Returning to situation types

We are now in the position to return to Noah’s incomplete construction of the ark. If your hunch was that the ind. aor. would be unacceptable as a way of communicating this actual event of an incomplete construction – congratulations, you were right! κατασκευάζειν is a verb that seems to imply the complete production of the thing that is referred to in the direct object. This means that if we look from outside at this situation, in a way that includes the end-point, i.e. the goal of the construction process, we can’t use this portrayal for an actual situation that does not contain the reaching of that goal.

By contrast, the imperfective aspect excludes the end-point from its reference time so that we can say Νῶε κατεσκεύαζε κιβωτόν in order to express the situation of an incomplete construction process.

Of course, this presupposes that we have correctly identified the situation type/actional potential of the verb constellation. Only if κατασκευάζειν contains such an inherent goal as its end point is what we’ve just said true. If it expresses only an activity of building without saying anything about completion then you can of course look at this whole situation and communicate it as such truthfully even if in a next step the construction isn’t finalized.

Now at last I think it has become absolutely clear why this classification of a verb constellation into different situation types is so crucially important for correctly reconstructing the situation that is meant by the author. To use the illustration yet again: If you don’t know what the actional potential of “to drown” is, you have no idea of whether “Bloggs drowned” implies his death or not!

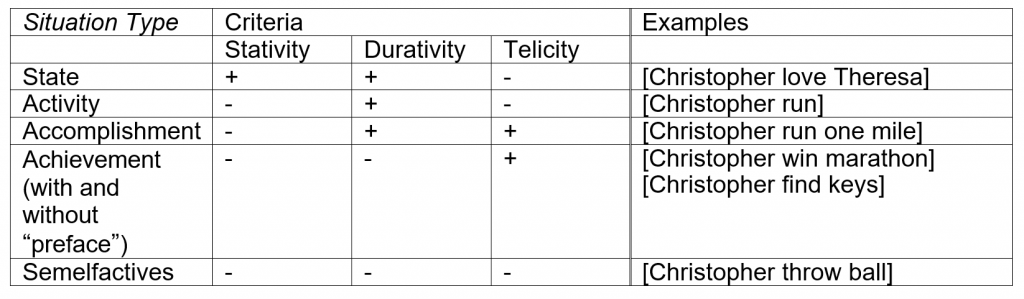

That being said, note also that not all possible classifications are equally useful. The table I produced above, for example, does not help us a lot with our question concerning κατασκευάζειν. It clearly is an action – but so what? The attempts to define the aspects above don’t touch on agentivity. Rather, what we need is the inclusion of the criterion “telicity.” It will tell us whether a situation contains an inherent goal that could be excluded in the imperfective aspect and would be included necessarily in the perfective aspect.

One system that includes telicity goes back to Zeno Vendler’s classic “Verbs and Times.” It has been used by Fanning and is still being used in The Greek Verb Revisited by many authors, though with some modification. (Check out in particular Mike Aubrey’s chapter for causative variants of these situation types.) Here’s the variant that Thomson uses:

That might look complicated at first look but is actually pretty simple. States and activities are both durative (they don’t last for just one moment) and they both don’t run towards a goal. But activities are not stative. By contrast to both states and activities, there are many situations that contain a goal, i.e. which are “telic.” Some of them take some time (accomplishments), others happen within a moment (achievements). And then there are semelfactives (not in Vendler’s original piece), which do not fulfil any of these requirements. [The lightning flash] is a very common example.

Outlook

There is certainly more to be said on this issue and my initial draft for this post included a more detailed exploration of how the imperfective and perfective aspect each interact with the different actional potentials that we have just explored. We have already seen what happens to an accomplishment like [Νῶε κατασκευάζειν κιβωτόν] in the imperfective aspect. It gets reinterpreted and appears in the shape of an activity. There are many similar dynamics that we need to be aware of. But if some of this stuff is new to you, this might already be quite a bit to take in.

So perhaps it’s best to make a break at this point so that you can think about the issues we’ve touched upon here on your own. Perhaps you can already develop a certain sense for how some of the situation types above might appear when looked upon in the various aspects. In part 4 of this series we will then continue were we’ve left and discuss how aspect influences the communicated situations. Also, we’ll consider shortly what all this means for our daily use of grammars and dictionaries. So stay tuned.

Further Reading

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Lexical Semantics and Lexicography

Part 4: Understanding Greek Verbs