Fasting was a popular religious practice in the time of Jesus. In fact, Mark 2 shows us that when Jesus and his disciples feasted instead of fasting, they drew some questioning looks. How could such a great religious teacher not take part in such a sacred discipline when other devout Jewish figures committed themselves so faithfully to fasting?

When Jesus answered the crowd’s challenges, he provided a new lens, a New Covenant lens, for making sense of the proper purpose and the appropriate time for fasting.

In this article, we will look at Mark 2:18–22 and conform our own understanding and practice of fasting into Jesus’s mold.

Table of contents

Questions about fasting begin festering (2:18)

Fasting is “voluntary abstinence from food for spiritual purposes.”1 While there are instances in the Old Testament of fasting to gain wisdom (e.g., 2 Chron 20:3), the primary theme surrounding the practice was mourning, and especially mourning over sin (1 Sam 7:6; Jonah 3:5–10; Joel 2:15; Ezra 10:6). 2 For instance, the Old Testament commanded only one mandatory fast, and that on the Day of Atonement (Lev 23:27–28), the solemn day each year that all of Israel would make sacrifice for the forgiveness of sin (Lev 16).3

After the close of the Old Testament and with the rise of Jewish asceticism, fasting became viewed “as a mark of religious devotion.”4 As such, the Pharisees, being themselves committed to the appearance of devotion, fasted twice a week (Luke 18:12; see also Mark 2:18). Likewise, disciples of John the Baptist, who had attracted quite a following with his wilderness ministry (Mark 1:5), also adopted fasting as a spiritual discipline (Mark 2:18).

But Jesus, this new teacher on the scene, who “taught … as one who had authority” (Mark 1:22) and had become famous “everywhere” (Mark 1:28), did not require fasting from his disciples. Some people noticed differences and asked, “Why?” (Mark 2:18). Perhaps onlookers were wondering, “Does this guy know something we don’t?”

The groom is here—so celebrate! (2:19–20)

Of course Jesus knows that fasting and mourning often hold hands in the Old Testament. Yet Jesus also knows that since he is on the scene, mourning needs to give way to rejoicing.

So Jesus answers by asking, “Can the wedding guests fast while the bridegroom is with them? As long as they have the bridegroom with them, they cannot fast” (Mark 2:19). A wedding is no place to diet. Men piously fasting make miserable wedding guests. The dinner, cake, drinks, and the joy that the bridegroom brings are wasted on the fasting guests.

Jesus sees himself as the Bridegroom, and thus his presence is a cause for celebration, not mourning (see Isa 62:5). The skies have been “torn open” and God has spoken (Mark 1:11); God’s redeeming love has come in Jesus Christ. Jesus is casting out demons (Mark 1:21–28), healing many (Mark 1:29–34), and forgiving sins (Mark 2:1–12). Now is the time for rejoicing, for feasting.

Jesus sees himself as the Bridegroom and his presence is a cause for celebration, not mourning.

Jesus emphasizes that his presence creates an epoch of joy when he says, “The days will come when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they will fast in that day” (2:20). There is a day for fasting, but now is not that day. When Jesus is here, it’s a day of celebration.

Like a new patch or wine (2:21–22)

As a wedding marks a beginning for husband and wife, so the incarnation marks a new beginning for the people of God. Jesus’s arrival requires us to rethink everything in light of his ministry, especially the way we approach our transgressions and fasting. This Jesus illustrates, speaking of wine and patches (Mark 2:21–22).

I know nothing about wine, but Jesus knows. He knows you cannot put new wine into old containers (Mark 2:22). Nor can you put a new patch on an old skin (Mark 2:21). The new patch and the new wine are stronger and far superior, so out with the old and in with the new. Schnabel summarizes the meaning of the analogy by saying, “Combining the new with the old will have disastrous consequences.”5

Jesus proclaimed the good news in his first Markan sermon, “The time is fulfilled, the kingdom of God is at hand” (Mark 1:15). Everything promised to Israel, all the redemption guaranteed through prophets, had arrived in the person and work of Jesus Christ; now, the kingdom of God had arrived. A new era had begun.

If you try to fit Jesus into the old molds, or the invented Pharisaic molds, they will burst. The old concealed the new, but the new will burst the old. Jesus’s answer, consisting of a single question and a double illustration, effectively says, “Everything you’ve thought about fasting must now be reconsidered because of me.”

Jesus reshapes everything—including fasting

The time is fulfilled and the moment of the long-awaited redemption has dawned in Jesus Christ. He fulfills what has come before and inaugurates a new era of relating to the Father (Heb 8:6–13). Thus Jesus’s presence (Mark 2:19) must reshape the way his people think about everything (e.g., see also Jesus’s treatment of the Sabbath in the very next passage; Mark 2:23–28)—including fasting.

If the primary catalyst for fasting in the Old Testament was mourning over sin, a practice woven together with repentance and longing for satisfactory atonement, Christians considering fasting must acknowledge that Jesus made the once and for all sacrifice for sin (Heb 10:10). Remember that the Old Testament commanded only one fast, on the Day of Atonement. The Day of Atonement has come and gone (1 John 2:2). The Bridegroom has come unto his people and given himself to sanctify and purify a bride for himself (Eph 5:25–27).

Jesus’s presence must reshape the way his people think about everything—including fasting.

So it makes sense that Jesus’s words on fasting Mark 2:18–22 point ahead to that hill far away and its old rugged cross. Notice his language. He says that when he is “taken away,” then there will be a time for fasting (2:20). The word “taken away” indicates “removal by force rather than by natural causes.”6 Jesus knew that in order to redeem his people from their sins over which they mourned and fasted, he would be “taken” to his death (Mark 8:31; 9:30–31; 10:33).

Jewish leaders—no doubt committed to pious fasting, yet sin-sick in their hearts—arrested, accused, and then “led him out to crucify him” (Mark 15:20; see Mark 14:43–49, 53–65; 15:1–5). There, these sinful men, aided by Roman soldiers, nailed Jesus to the cross and “they crucified him” (Mark 15:25). On the cross Jesus, the New Wine, was offered “wine.” According to Mark, though, Jesus did not drink (Mark 15:23). The time for wine had come to a close; the Son of Man “breathed his last” (Mark 15:37).

Yet, with his last breath, the same power that ripped the heavens open at Jesus’s baptism (Mark 1:9–11) tore the temple veil which symbolized humanity’s separation from God (Mark 15:38). Jesus’s blood, the new wine (Mark 14:24), was poured out as a pleasing offering to rescue mankind lost in sin (Col 1:14).

New covenant fasting

Yet, as Jesus says, there nonetheless remains a day for fasting, for choosing to abstain from food and drink for spiritual reasons. The Lord is not present with us, and so that day is now (Mark 2:20).

But if the remedy for our sorrow over sin is met in Christ’s cross (Rom 3:21–26), why then do we continue to fast? How does Jesus’s life and ministry reshape this spiritual discipline?

This “good news,” proclaimed by Jesus (Mark 1:14–15) and accomplished by his death, must shape the way we, his disciples, consider fasting today. We must approach fasting with a focus on the new rather than the old, for the old is fulfilled and the new is revealed. A covenant written in the blood of the Son of Man must shape our thoughts and reasons for fasting, not a covenant written in laws.

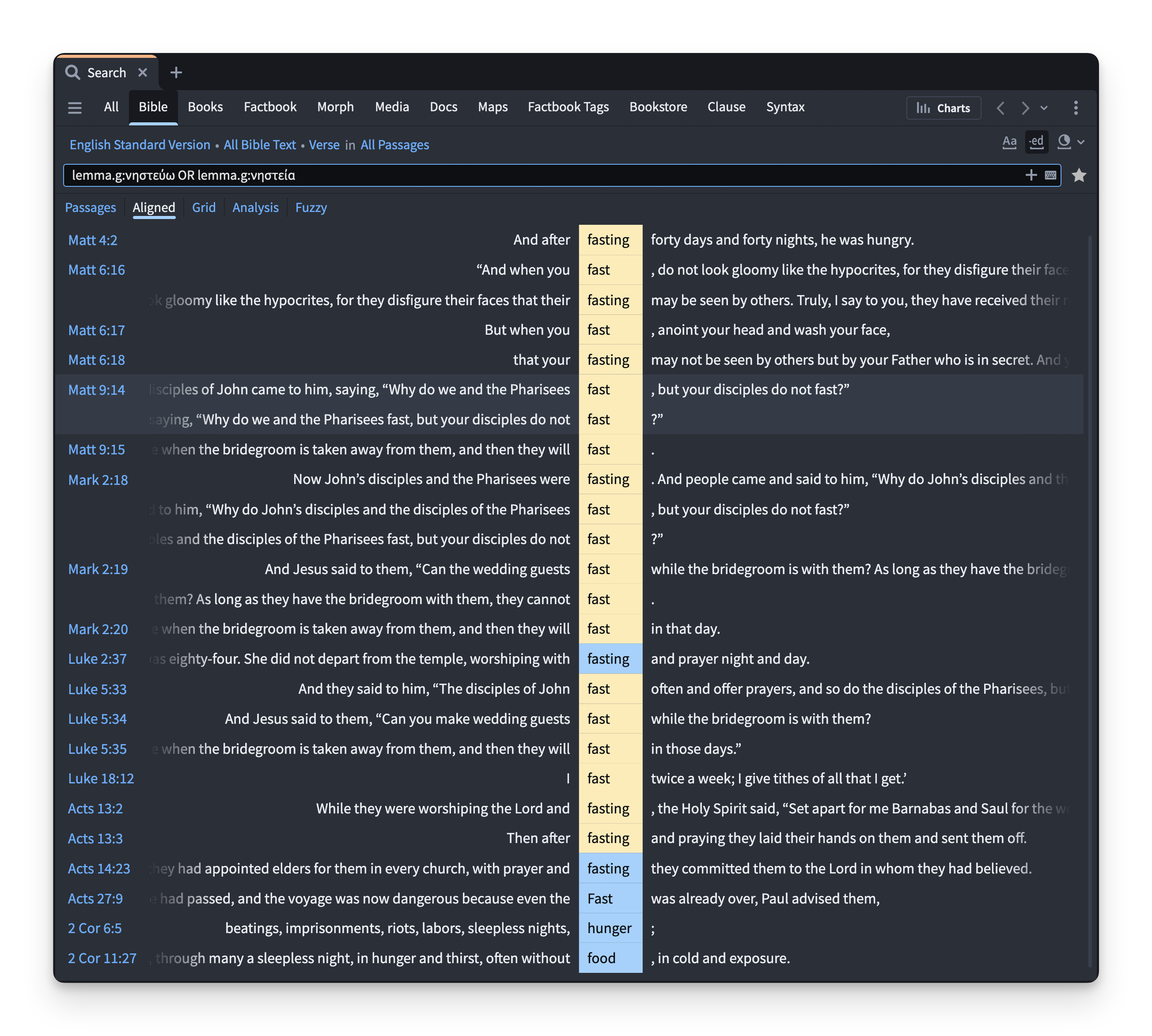

Use Logos to locate every instance of words like “fasting” (noun) and “fast” (verb) across the New Testament

For instance, not once in the New Testament is fasting associated with Christians mourning over sins committed or as a response to their failure to live righteously. Rather, Christians fast as we await the day when the Bride and the Groom will be reunited (Rev 21:1–8) and to seek wisdom in the midst of our waiting (Acts 13:2; 14:23). Knowing that Jesus’s presence is still with us by the ministry of the Holy Spirit (John 14:15–17), we embrace spiritual disciplines that help us enact the desire for the final consummation of all things. We long for the final feast day at the marriage supper of the Lamb, when the presence of Jesus will fill the longing in our hearts and we will never fast again (Rev 19:6–10).

Fasting in the New Covenant, then, is a response: a response to a desire to have Christ, to behold his face, to be wed to him forever. It is a response to our need for his divine wisdom in our lives right now (Acts 13:2–3) even while we look for his coming again. Don Whitney gets to the point:

Fasting sometimes seems the only way to answer the ache in our hearts for the consummation of all things, for the time when we are at last with God and all things are restored, made new, and made right. Until the Bridegroom returns for His bride, He knows these yearnings for Him will incline our hearts, with the rues to that we will fast.7

Fasting that acknowledges the ache

When you consider fasting, do not let old systems force you into a practice filled with unnecessary grief and sorrow. The “old has gone, behold the new has come” (2 Cor 5:17). Fasting is not the medicine for sin nor the power to overcome sin: the cross of Christ is (Col 2:13–15). By faith in Jesus Christ, you are the redeemed. Therefore, let Christ shape the way you think about abstaining from food and every other spiritual discipline.

While we grieve the fact that we still commit sin as the old and new wage war against one another, and while we long to “put on” more of Christ, to look like the new man and not the old self (Col 3:12; cf. 3:5, 8), it is the ache in our heart for Jesus’s final renewing work that should drive us to consider fasting.

We long for the day when Jesus, who is our life, appears (Col 3:4). Jesus tells us that if we truly long for that day, then we will fast for him.

Recommended resources from Chandler Wiley

Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life: Revised and Updated Edition

Regular price: $13.99

Related articles

- How to Fast for God: What Fasting Is, Why It Matters & More

- Lent: A Season to Dread or to Cherish?

- What Lent Is Really about—and How We Miss the Point

- You’ve Decided to Study the Gospels: Now What?

- How Mark’s Use of the OT Contributes to His Christology

- Donald S. Whitney, Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life, rev. ed. (NavPress, 2014), 192.

- Fasting was “practiced in the Bible primarily as a means of mourning. Fasting frequently occurs in the Old Testament in response to suffering or disaster, in conjunction with other mourning rituals.” David Seal and Kelly A. Whitcomb, “Fasting,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. John D. Barry et al. (Lexham Press, 2016).

- J. E. Hartley, “Atonement, Day Of,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch, ed. T. Desmond Alexander and David W. Baker (InterVarsity Press, 2003), 54–55.

- John Muddiman, “Fast, Fasting,” in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (Doubleday, 1992), 774.

- Eckhard J. Schnabel, Mark: An Introduction and Commentary, ed. Eckhard J. Schnabel, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (InterVarsity Press, 2017), 2:75–76.

- Schnabel, Mark, 75. Also see Wellum and Gentry where they connect Mark 2:20 and Jesus being “taken away” to Isaiah 53:8. Peter J. Gentry and Stephen J. Wellum, Kingdom Through Covenant: A Biblical-Theological Understanding of the Covenants, 2nd ed. (Crossway, 2018), 724.

- Whitney, Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life, 197.