In Acts 19:35, the Ephesus city clerk refers to an “image that fell from heaven”: “People of Ephesus! What person is there who doesn’t know that the city of the Ephesians is the temple guardian of the great Artemis, and of the image that fell from heaven?” (CSB; emphasis added).

What was this “image that fell from heaven”? Possibly the image itself is sitting in storage in the Liverpool Museums’ collection!

The Artemis tourism and disturbance in Ephesus (Acts 19:21–41)

When the apostle Paul and his friends ministered in Ephesus for several years, their gospel ministry cut into the profits of idol makers. Paul discounted their gods as having been “made with hands” (Acts 19:26 NASB). The silver workers’ financial losses motivated a disturbance led by a man named Demetrius, one of their own, who saw how preaching about Jesus had cut into the local souvenir trade.

In Luke’s description of the gathering and chanting that resulted, the city clerk delivered a speech in which he cited the city of Ephesus as the guardian of the “image that fell from heaven” (v. 35 CSB). This exact phrase (or something close to it) is how translators usually render the Greek τοῦ διοπετοῦς into English (see CSB, NASB, NIV), though the KJV translates it as “the image that fell down from Jupiter.” That’s because the Greek διοπετοῦς bears the name “Dio”—Greek for “Zeus” (Roman, “Jupiter”). In other words, the city was the keeper of the “Zeus-fallen.”

Using Logos’s Bible search, we can search for an exact Greek phrase and add translations to see how they compare. Get the Logos app free, if you don’t already have it.

Zeus was Artemis’s father. And Ephesus was Artemis’s natal city as well as the home of her great temple—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

So what exactly was the “Zeus-fallen” (διοπετοῦς) to which the clerk referred? An artifact sitting in storage in the Liverpool Museums may provide the answer.

The British discover an Ephesian artifact

In the 1860s, the British Museum funded excavations in Ephesus, making it possible for John Turtle Wood to discover the site of the ancient temple of Artemis (1869). The Museum’s work continued in the city until 1874, when the Austrians took over. But many British archaeologists continued the work they’d started.

About eighty-five years ago, a British archeologist and classics scholar named Arthur Bernard Cook, best known for his three-part work, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion (1940), described an object from Ephesus that one of his fellow researchers—one Sir William Ridgeway—told him about. Ridgeway said a member in the consular service at Smyrna (only about thirty-five miles from Ephesus) found a remarkable artifact along with “arrow-heads and other items from Ephesos.”1Arthur B. Cook, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, vol. 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940), 900.[/note](Spellings of the city vary.)

Initial interpretations of the artifact

Sir William detected what he considered the artifact’s true character. He saw it as a great example of an aniconic—that is, a symbolic rather than literal—deity. Sir William intended to publish his opinion, but he died in the late 1920s before he was able to do so.

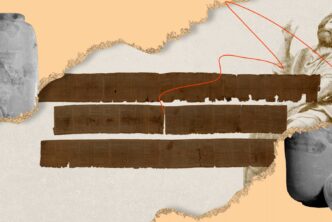

Sir Williams’s daughter and the then-president of Queen’s College, Cambridge, where the piece was being held, passed it into Cook’s possession.2 After analyzing it, he determined the artifact was a sacred stone thought to be endowed with life or access to a deity, most commonly Zeus. Some such stones were assumed to be meteorites and dedicated to a god or revered as a symbol of the god him- or herself.

Cook dated this particular piece’s decoration to ca. 2000 BC, noted its size as 6.25 inches high, and described it as being of “dull green stone.” He believed it had been “facetted and inlaid with tin,” with the sort of faceting that occurred “sporadically throughout central Europe towards the end of the stone age.”3 And he saw in its shape a somewhat human form. From all this he drew a startling conclusion:

The really remarkable thing about our pounder is the arrangement of its decoration, which transforms the neolithic tool into a quasihuman shape. The head is surmounted by a conical tin cap, secured by three tags or tenons of tin, any one of which might suggest a nose. The shoulders are covered by a broad tin cape. The waist is represented by a deep groove. Below this is a double belt of tin. Lower down, the facetted surface looks like folds of drapery encircled by a tin band, from which hang four pairs of tin pendants symmetrically placed. Finally, at the foot, opposite each pendant is a hole for the insertion of a stud, perhaps of amber or vitreous paste. In short, we may venture to recognise a primitive idol comparable with the bottle-shaped goddesses figured on coins of Asia Minor. … It is therefore tempting to compare this humanised pounder with the “Zeusfallen” image of Artemis Ephesia. And all the more so, when we learn that, by an impressive coincidence, the pounder actually came from Ephesos.4

Sacred headgear

Sometime later, in 1952, Charles Seltman, a British numismatologist (an expert in coins) proposed an interpretation of the Acts wording, “Zeus-fallen.” Instead of referring to a cult statue, as one might expect, he proposed it was actually a “small, additional object—perhaps a Neolithic artifact—which was also sacred and housed in the temple.”5

Seltman regarded the temple-shaped headgear of several images as “representations of a small shrine, replicas of which were made by the silversmith such as Demetrios, in which such an object would be housed.”6 In his view, the piece was not a depiction of the goddess herself, but rather something she wore atop her head.7

Quickly research Artemis and other New Testament background info with the Factbook inside Logos. Get the Logos app free, if you don’t already have it.

Not from the heavens after all

Eight years later, Kenneth Oakley, an anthropologist, paleontologist, and geologist who dated fossils and worked with the British Museum, learned that Cook had sold this primitive piece from Ephesus to the City of Liverpool Museums.8 So Oakley asked if the British Museum’s Natural History department could analyze it.9

The Museum’s Keeper of Mineralogy at the time confirmed immediately that the piece did not come from the heavens; rather, it was terrestrial schist. That is, greenish rock composed of mineral grains that can be easily split into plates or flakes. Subsequently, Oakley learned that someone at Cambridge had already made the same determination.

Further, Oakley noticed the figure was inset with four pairs of tin pendants, symmetrically shaped.10 He observed that the entire piece’s shape conformed to that of ancient idols resembling ancient Neolithic implements often supposed to have fallen from the sky. Oakley concluded, “It is therefore temping to compare this humanized pounder with the ‘Zeus fallen’ image of Artemis Ephesia” mentioned in the book of Acts.11 Writing for Folklore, he recounted how an archaeology professor at Cambridge hypothesized that the diopet was preserved in the temple of Artemis throughout ancient times until the conversion of the Roman world to Christianity, after which the cult of Artemis petered out and the temple fell into decay.

Further, Oakley recounted how “the late Miss Elaine Tankard, while Keeper of Archaeology in the Liverpool Museums, made an interesting suggestion as to how the Diopet was placed in the shrine. She said it would have fitted perfectly if worn in the crown of the statue of Artemis as this appears in existing replicas.”12

Oakley felt it was by “impressive coincidence” that “the pounder actually came from Ephesos.”13 Oakley’s narrative and findings thus aligned with Seltman’s proposal that the diopet of Acts referred not to a statue but rather a small, Neolithic, sacred artifact housed in Artemis’s temple and associated with the statue’s head gear.

A more recent Ephesus researcher, Lynn LiDonnici, has concluded,

Seltman regarded the temple-shaped headgear of several images of Artemis Ephesia as representations of a small shrine (replicas of which were made by the silversmith Demetrios) in which such an object would be housed. This is an interesting possibility, especially since it explains the mysterious change to masculine gender for adjectives modifying της μεγάλης ‘Αρτέμιδος (“the great Artemis”).14

Additionally, the evenly placed pairs of tin pendants may provide clues as to the identity of Artemis Ephesia’s so-called breasts—they were perhaps shapes borrowed from the diopet.

The real deal?

When researching my book Nobody’s Mother: Artemis of the Ephesians in Antiquity and the NT (IVP Academic, 2023), I contacted the Liverpool Museums to verify that the artifact was still in their possession. They confirmed that indeed it was (and is) still there. Two experts in their employ even offered to take a photo of it for me. And yes, the museum still has the artifact labeled as the “Diopet of Ephesus.”

I suspect the artifact is the real deal. But whether or not the piece in the Liverpool Museums’ possession is the one to which Luke referred in the book of Acts, the piece affords readers a look at the possibilities of what the city clerk of Ephesus could have meant when he referred to Ephesus as guarding something “Zeus-fallen.”

Continue studying the background of Acts with these resources

Acts: Volume 2B (Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary)

Regular price: $29.99

Acts (Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament | ZECNT)

Regular price: $59.99

Related articles

- No Longer Captives: Released from the Cage of Romans 7

- What Does the Vision in Ezekiel 1 Mean?

- Freedom of the Spirit: What Paul Means in 2 Corinthians 3:17

- Arthur B. Cook, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, vol. 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940), 900.

- Cook, Zeus, 900, fn. 3.

- Cook, Zeus, 898.

- Cook, Zeus, 899–900.

- Charles Seltman, “The Wardrobe of Artemis,” Numismatic Chronicle 6, no. 12 (1952): 33–44.

- Seltman, “Wardrobe of Artemis,” 33–44.

- Margaret Warhurst, “The Danson Bequest and Merseyside County Museums,” Archaeological Reports 24 (1977–1978): 85–88.

- K. P. Oakley, “The Diopet of Ephesus,” Folklore 82, no. 3 (1971): 207–11.

- Oakley, “Diopet of Ephesus,” 207.

- Oakley, “Diopet of Ephesus,” 209.

- Oakley, “Diopet of Ephesus,” 210.

- Oakley, “Diopet of Ephesus,” 210, fn. 3.

- Oakley, “Diopet of Ephesus,” 210.

- Lynn LiDionnici, “The Images of Artemis Ephesia,” Harvard Theological Review 85, no. 4 (1992): 395, fn. 27.