Irenaeus of Lyons is essential to any study of early Christianity, whether theological or historical. He was an important witness to events, episodes, and people at a critical moment in Christianity’s early growth. He was also the first to practice theology as we know it today—as a reasoned reflection on the data of divine revelation.

His writings may also be overdue for a comeback.

Table of contents

Irenaeus’s life and ministry

The date of Irenaeus’s birth is unknown. He spent his boyhood in Smyrna (modern Izmir, Turkey) and passed much time in the company of the city’s bishop, Polycarp. Later in life he recorded memories of those years. Since Polycarp died as a martyr in AD 155 and Irenaeus recalled being a “boy” in his presence, he was probably born no later than 140, though perhaps as early as 120.

Polycarp was profoundly influential in Irenaeus’s intellectual and spiritual development. In a letter to a lifelong acquaintance, he wrote:

I remember the events of that time better than what has happened recently (for what we learn as children grow up together with the soul, and is united to it), so that I can describe the place where the blessed Polycarp sat as he dialogued, and his exits and entries, and the character of his life and the form of his body … [he] proclaimed everything in accordance with the writings [of Scripture].1

The next we hear from Irenaeus, he is a young man who has gone west. He is in the city of Lugdunum (modern Lyon) in the Roman province of Gaul, and he is serving as a priest. He may have arrived with the city’s first bishop, Pothinus, a fellow Smyrnaean and disciple of Polycarp.

Irenaeus won local renown among the clergy and laity. In a letter from 177 commissioning him as their emissary to the bishop of Rome, the priests of Gaul praise their “brother and comrade Irenaeus” as “zealous for the covenant of Christ.” They continued: “For if we thought that office could confer righteousness upon any one, we should commend him among the first as a presbyter of the church.”2

His mission was to raise alarms about Montanism, a heresy that began in Phrygia (now central Turkey) but quickly spread throughout the Roman world. This is the first glimpse we have of Irenaeus in a role he would pioneer: heresiologist. Yet even here he was surely inspired by Polycarp, who once met the heretic Marcion on a street in Rome and called him out as “the firstborn of Satan.”3

As Irenaeus left on his mission to Rome, many of his colleagues were in prison. When he returned, many of them were dead: victims of a wave of local anti-Christian persecution. The elderly bishop Pothinus had also died in the violence.

Irenaeus, by now something of a celebrity, was the obvious choice as successor to Pothinus. He served as bishop of Lugdunum for at least thirteen years, but perhaps many more.

We know almost nothing about Irenaeus’s pastoral and administrative activity. We know of one more embassy he made to Rome, around 190, to plead with Victor, the bishop of Rome, not to excommunicate Easterners who celebrated Easter on its anniversary date rather than the nearest Sunday. He succeeded in this, and he returned to his see. All we know of his remaining years is his remarkable literary production.

Use Logos’s Advanced Timeline to locate subjects, like Irenaeus, across church and biblical history.

Irenaeus and the problem of Gnosticism

Heresy was not something new in the late second century. Nor was it peculiar to Gaul. Already in the time of the apostles, Paul warned against aberrant doctrine (see 1 Tim 1:3–4; 4:1–3). All of the Apostolic Fathers took time to fret over heresies. For Ignatius of Antioch, it was the Docetists and the Judaizers; for Clement, it was the Corinthian rebels; for Polycarp, it was Marcion.

But by the late 100s, the heresies were metastasizing, spreading rapidly and changing as they spread. They were a cancer in the body of the church, distracting and confusing people, dividing congregations, and draining energy from evangelism.

Irenaeus took up the task of studying the phenomenon scientifically. He read the literature from each sect and identified what was distinctive about them. But he also noted errors that were common to all.

The movement was called Gnosticism, from the Greek word for knowledge (gnosis). This gnosis referred to “secret knowledge” all the various gnostic teachers claimed to possess which could advance individuals beyond the elementary doctrine contained in the Gospels. They claimed that the truth contained in the Gospels actually contradicted the common understanding of ordinary Christians. The books of the Bible were coded in such a way that most people could read them one way, but only the elite could see their “hidden truth.”

Many gnostics, for example, rejected the Old Testament. They believed the Creator portrayed in Genesis was an evil force who designed the material world to be a trap for good spirits. Those good spirits were emanations of a higher god and needed to move beyond matter in order to return home. Various gnostic systems provided passcodes or other techniques for advancing beyond the gatekeepers of the cosmos. Gnosticism succeeded because people wanted a better spiritual life, but also enjoyed being flattered as better spirits, more refined than the other parishioners.

As bishop, Irenaeus recognized this as a serious danger—more dangerous, in fact, than Roman persecution, which he had seen claim the lives of many Christians. Gnosticism was uninterested in bodily life, but threatened to corrupt the spiritual life of entire congregations.

“Secret” doctrine was cheap and could be produced by anyone who claimed to be a teacher. For Irenaeus, though, a strength for Christianity was the fact that it was verifiable. It kept no secrets. Its Scriptures were public and their words were plain. Its teachers were publicly known (as bishops and presbyters) and their pedigrees were common knowledge. Christianity was (and is), moreover, catholic—that is, it’s universal: Its beliefs do not change from teacher to teacher, or even from country to country.

Irenaeus himself was evidence of this. As bishop, he was successor to Pothinus, who was ordained by Polycarp, who was himself a disciple of the Apostle John, who was in turn a disciple of Jesus. Irenaeus learned to interpret the Scriptures in faraway Smyrna, but what he learned was fully applicable in the chief city of Gaul.

Gnostic teachers might propose fanciful interpretations of the biblical books, but bishops—like Polycarp, Pothinus, and Irenaeus—bore the authority of a tradition that went back to Jesus, God incarnate. If you wanted to know the teaching of Christ and his church, you could look it up.

Iranaeus’s Against the Heresies

To counter gnostic teaching, Irenaeus composed his sprawling five-volume work Adversus Haereses. In Greek, the word haereses meant “schools of thought.” But in Irenaeus’s work, it took on a negative coloring. It meant the rejection of a doctrine that is essential to the gospel. This is where we get the word “heresy.”

Adversus Haereses is a meandering work. In books 1 and 2, Irenaeus takes up each gnostic teacher in turn and refutes his teachings. Since many of these men shared doctrine in common, there is redundancy in the refutations.

Irenaeus occasionally breaks up the monotony with humor. After exposing the gnostic Valentinus for his invention of meaningless buzzwords, Irenaeus offers a parody of Valentinus’s speculation, replacing gnostic jargon with words like gourd, cucumber, and melon:

These powers, the Gourd, Utter-Emptiness, the Cucumber, and the Melon, brought forth the remaining multitude of the delirious melons of Valentinus. For if it is fitting that that language which is used respecting the universe be transformed to the primary Tetrad, and if anyone may assign names at his pleasure, who shall prevent us from adopting these names, as being much more credible [than the others], as well as in general use, and understood by all?4

A turn comes with book 3, however. There, Irenaeus begins a positive articulation of the faith of the church: an exposition that is both biblical and systematic. In the final three books, he makes the case for a coherent, cohesive, normative Christianity that cannot accommodate Gnosticism’s speculation and innovations.

Gnostic sects were as varied as their teachers. Their Scriptures were many and mutually contradictory—attributed to the apostles, but published only recently. By way of contrast, Irenaeus makes his case that the fourfold Gospel (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) is reliable because it is ancient and has enjoyed universal acceptance by Christians.5

He argues that the office of bishop is similarly reliable because it is ancient and verifiable. He writes:

It is within the power of all, therefore, in every Church, who may wish to see the truth, to contemplate clearly the tradition of the apostles manifested throughout the whole world; and we are in a position to reckon up those who were by the apostles instituted bishops in the Churches, and [to demonstrate] the succession of these men to our own times.6

Thus he rounds out his presentation of a sacred order, an authoritative hierarchy, within the church, with touchstones that guarantee unity in doctrine and practice. For “the Catholic Church possesses one and the same faith throughout the whole world.”7

The faith of the church is recognizable in preaching and doctrine, Irenaeus insists, because it always follows the same pattern. It presents Christianity’s non-negotiable truths and admits no innovation or deviation. He writes:

The church, though dispersed throughout the whole world, even to the ends of the earth, has received from the apostles and their disciples this faith:

She believes in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven, and earth, and the sea, and all things that are in them; and in one Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who became incarnate for our salvation; and in the Holy Spirit, who proclaimed through the prophets the dispensations of God, and the advents, and the birth from a virgin, and the passion, and the resurrection from the dead, and the ascension into heaven in the flesh of the beloved Christ Jesus, our Lord, and His [future] manifestation from heaven in the glory of the Father to gather all things in one (Eph 1:10) and to raise up anew all flesh of the whole human race.8

In his battle with the gnostics, Irenaeus seems to have won. His arguments were persuasive and clear, and the heresy ceased to be a movement, at least for a while. It has resurfaced in history in various forms: Manichaeism in the third century, Albigensianism in the eleventh.

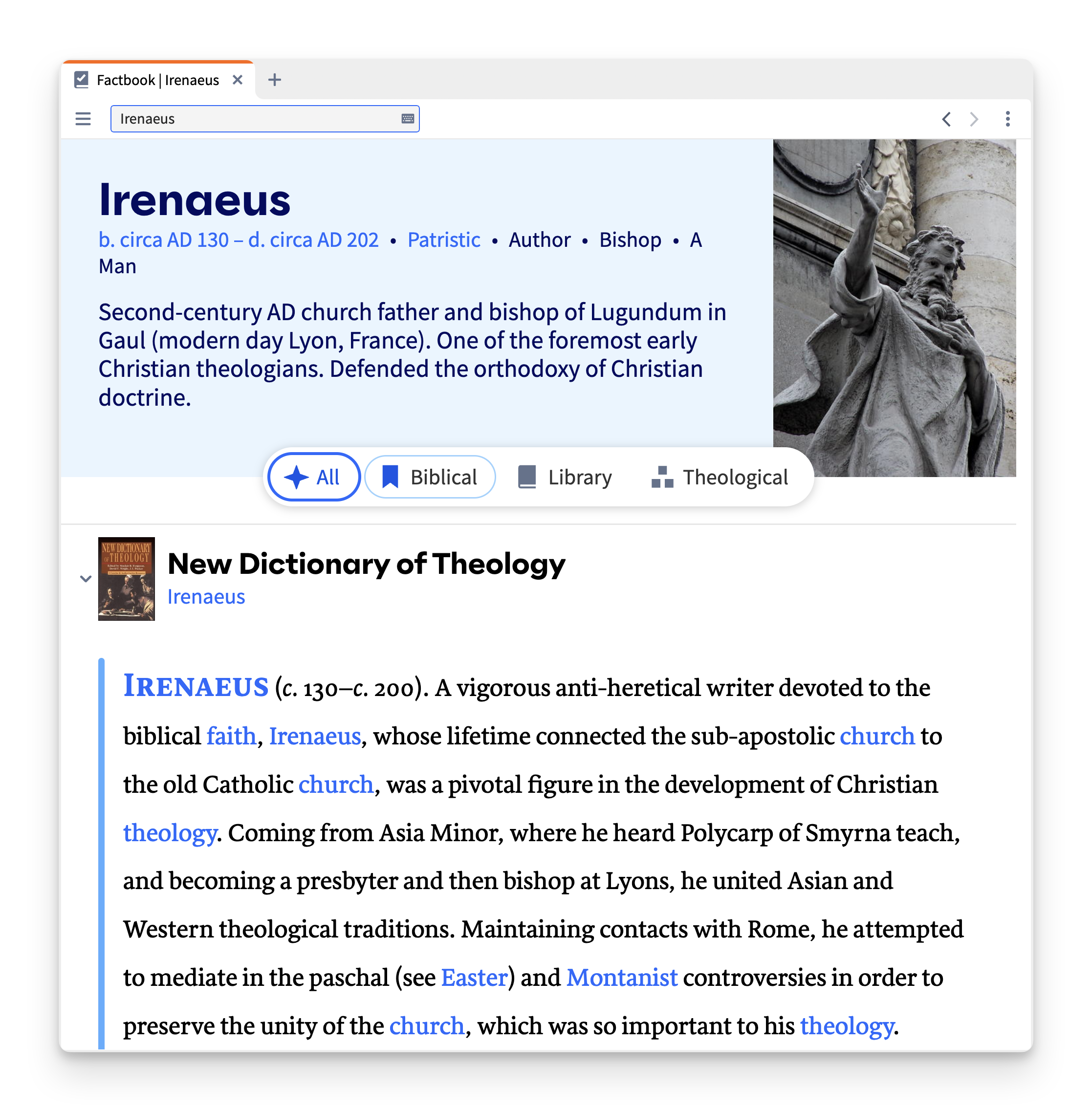

Launch your own study of Irenaeus with Logos’s Factbook.

Iranaeus’s legacy

Gnosticism is arguably on the rise in our own time. Jordan Edwards recently observed that “both new age sects and secular proponents of abolishing gender and sexuality can be traced to the influence of Gnosticism, for in all of these beliefs, the dualistic notion that one’s body is not one’s true self holds supreme.”9 Yale literary critic Harold Bloom referred to Gnosticism as “the American religion.”10 And Pope Francis has described the gnostic tendency in Christianity as “a purely subjective faith whose only interest is a certain experience or a set of ideas and bits of information which are meant to console and enlighten, but which ultimately keep one imprisoned in his or her own thoughts and feelings.”11

It may be time for Irenaeus to take a comeback tour, at least on our bookshelves, hard drives, and mobile devices.

Irenaeus’s other works

For centuries—indeed for most of Christian history—Adversus Haereses was the only work of Irenaeus known to have survived in its entirety. Eusebius, in his History of the Church, quoted short passages from Irenaeus’s Letter to Florinus, a fellow Smyrnaean who took up the heresy of Valentinus. Eusebius also mentions a work, On the Ogdoad, aimed directly and entirely at Valentinus.

Another work, On the Apostolic Preaching, was known only as a title on ancient lists—but was (re)discovered in Armenian translation in the early twentieth century. It is a striking, straightforward summary of the Christian faith and salvation history—and the earliest Christian writing of its kind.

Conclusion

From the latter decades of Irenaeus’s life, only his authorial voice survives. We have no witnesses to his episcopal acts. We have no witness to his death. He is remembered in some churches as a martyr, but no less a scholar than Johannes Quasten has called that claim into question, as there is no account of his martyrdom known before the sixth century.

The abiding testimony to his character is his work, and that is enough. In 2022, some 1,800 years after Irenaeus set down his last written words, Pope Francis declared him a Doctor of the Church, recognizing him as one of the most significant teachers of theology and doctrine in all of history.

Recommended resources

Related articles

- Know Your Heresies: How Not to Be a Heretic

- How the Early Church Found the Trinity in the Old Testament

- The Marvelous Grace of God: What Scripture & Church History Reveal

- Irenaeus of Lyons, Letter to Florinus, in Eusebius, The History of the Church, trans. Jeremy M. Schott (University of California Press, 2019), 5.20.6.

- Quoted in Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History 5.4.2, trans. Arthur C. McGiffert, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series (Hendrickson, 2004), 1:219.

- Irenaeus of Lyons, Against the Heresies, trans. Dominic J. Unger (Newman Press, 1992), 3.3.4.

- Irenaeus, Against the Heresies 1.11.4.

- Irenaeus, Against the Heresies 3.11.8.

- Irenaeus, Against the Heresies 3.3.1.

- Irenaeus, Against the Heresies 1.10.3.

- Irenaeus, Against the Heresies 1.10.1.

- Jordon H. Edwards, “Gnosticism,” in The Essential Lexham Dictionary of Church History, ed. Michael A. G. Haykin (Lexham Press, 2022).

- Harold Bloom, The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (Simon & Schuster, 1992).

- Pope Francis, Apostolic Exhortation on the Call to Holiness in Today’s World, Gaudete et Exsultate (April 9, 2018), 36.