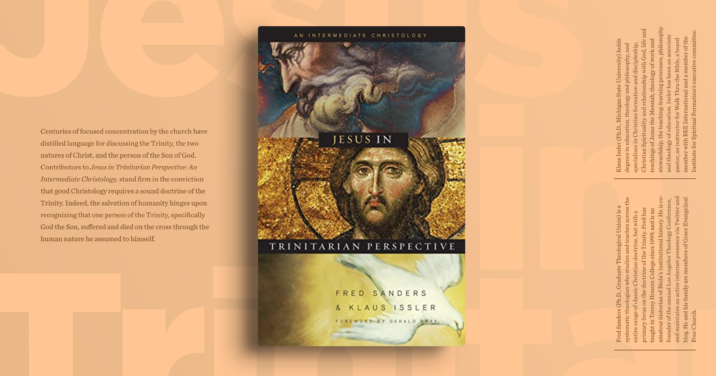

Centuries of focused concentration by the church have distilled language for discussing the Trinity, the two natures of Christ, and the person of the Son of God. Contributors to Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective: An Intermediate Christology,1 edited by Fred Sanders and Klaus Issler, stand firm in the conviction that good Christology requires a sound doctrine of the Trinity. Indeed, the salvation of humanity hinges upon recognizing that one person of the Trinity, specifically God the Son, suffered and died on the cross through the human nature he assumed to himself. One of the challenges when discussing Christology is that concepts and vocabulary developed throughout church history, often in the context of controversy, remain out of reach for many Christians. Fortunately, there is a resource, available through Logos, which can provide clarity in Christology. Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective (JTP) aims to situate Christ within the Trinity while familiarizing readers with the terminology that has developed when the church talks about Christ.

Summary

Fred Sanders begins the book with “Introduction to Christology.” Sanders states at the beginning that the purpose of the book is “to clarify the doctrine [of Christ in relation to the Trinity] for the benefit of those who desire to know what they are believing when they believe” (9). To that end, authors have been selected based on their expertise to address specific topics related to Christology. Especially helpful is the overview Sanders provides of the first four great councils of the church—Nicaea (325), Constantinople I (381), Ephesus I (431), and Chalcedon (451)—which highlights the various reasons for each council while also bringing the reader along to the primary focus of the book: the Chalcedonian categories which serve to define orthodox Christology.

J. Scott Horrell boldly embarks on trinitarian considerations in his chapter, “The Eternal Son of God in the Social Trinity.” The Bible, particularly the New Testament, is the ground for one’s understanding of the Trinity. However, human understanding of God based on what has been revealed in Scripture (the economic Trinity) does not by any means exhaust all there is to know about God (the immanent Trinity). Nevertheless, one can know the nature of the Godhead and the inner dynamic of the Godhead as they relate to one another. This Horrell pursues in order to identify the personal and relational order that exists in the Trinity between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, especially as it pertains to the giving of the Son by the Father and the progression of the Spirit, without succumbing to an implicit hierarchical subordination.

Donald Fairbairn’s chapter, “The One Person Who Is Jesus Christ,” emphasizes the patristic Christological perspective by focusing on and rehabilitating to some degree Cyril of Alexandria as “the Christian church’s most significant Christological teacher” (80). Rehearsal of historical narrative of Christological contemplation reveals that when the early church rejected a particular Christological view, it meant rejecting a particular soteriological view. The battle was waged concerning whether salvation is dependent upon (mostly) human effort with “no particular need for God to enter human life personally” or if salvation is the work of God so that “God the Son himself must personally step into human history” (96). Cyril’s contribution to the Chalcedonian Definition here is vital. At the same time, the new contribution and the primary emphasis of the Chalcedonian Definition are not the same. The new contribution involved the application of the words prosopon and hypostasis to Christ’s single person. The primary emphasis, though, is evidenced by the repetition of the phrases “the same one” and “one and the same” (105–06). Thus, what Cyril states explicitly Chalcedon merely implies: God the Son died on the cross in his flesh.

Garrett J. DeWeese’s chapter, “One Person, Two Natures,” provides the philosophical framework needed for discussing Christ’s natures and person. Some of the groundwork for this chapter had been laid earlier by Horrell in his discussion of the Latin and Greek terms utilized in the early church for talking about nature and personhood (49–53). DeWeese advances the discussion further, offering two metaphysical models, “one historical, one contemporary” (117), which aim to illuminate how the incarnation was accomplished. These models are based on the locus of the will, either in the nature (historical model) or in the person (contemporary model). The historical model argues that the will is situated in the nature and therefore concludes that Christ had two wills (dyothelism): one human and one divine. After tracing out the problems inherent in the dyothelite model, DeWeese moves to the contemporary model which argues that the will is situated in the person, thereby concluding that Christ has a single will (monothelism): Christ’s will belonged to his divine person (144). Some have leveled the charge of Apollinarianism at this model, but DeWeese works to avoid that misnomer (146–49).

The final two chapters examine the work of Christ in relation to the Trinity. Bruce A. Ware situates “Christ’s Atonement” within a trinitarian perspective. He frames his chapter around the question, “Why must God be three in one for salvation to be effected?” (158). Ware argues at length that the Son was chosen and sent by the Father from eternity to accomplish pardon from sin for humans. The Son in turn voluntarily empties himself so that he can come into the world and do the Father’s will. He then lives by the Spirit so that he can offer “unceasing, free obedience” to his Father (175). The Son’s Spirit-aided obedience culminates in death on the cross in order that the Father’s just judgment could be satisfied and human sin atoned for in Christ. So the Son obeys the Father by the Spirit, an ordering of the life of the Trinity (taxis) issuing from eternity and revealed in the reality of atonement wrought in Christ.

Continuing these considerations, Klaus Issler explores “Jesus’ Example” for believers. Once atonement has been made, the Christian has an obligation to walk worthily before the God who redeemed him. The example of Jesus is what Christians are to look to and imitate. The problem that immediately arises for Christians is that Jesus was not only human: he was divine in nature. So, therefore, he had an advantage other humans did not. Issler argues that, in fact, Jesus of Nazareth was “predominately dependent” upon the resources of his Father and the Spirit due to his setting aside of his rightful divine prerogatives (Issler’s explanation of kenosis). In this way, he firmly establishes Christ’s life in relation to the other two persons of the Trinity. Issler provides dozens of examples from the Gospels and briefly answers several objections before demonstrating his model from a specific event from the life of Christ: the boy Jesus in the Temple. He speculates that the Holy Spirit served to shield the boy Jesus during his formative years, the Spirit serving as “his inner divine tutor” as he grew and matured to manhood. So while there are unique aspects of Christ’s life that remain unique to him, the overall Spirit-filled life of Christ serves as an example for all Christians to imitate.

Analysis

One of the challenges of a work like this is that one is dependent upon the pre-established language and definitions. Theologians of the past have introduced and utilized language to specify what they are communicating. The danger lies in anachronistically reading modern psychological terms and definitions back into the language utilized by early church writers to discuss person (e.g., hypostasis, persona). DeWeese admits words change over time and are dependent upon the theological and philosophical contexts in which they are used (118–19). Yet even with this admission, he begins with current philosophical categories in order to work out his contemporary metaphysical model. In addition, he seemingly conflates terms which early theologians distinguished. For example, he uses “nature” and “essence” interchangeably, yet the early church writers differentiated between physis and ousia.

So besides being able to pepper hypostasis and ousia into everyday conversation, why would the average Christian want to pick up this book? First, Christ is the heart of the gospel. This book gave me a firmer grasp of Christ which in turn gave me a firmer grasp of the gospel. Second, Christ is the revelation of the triune God. A better understanding of Christ means a better understanding of God. Indeed, a stated goal of this book is to help readers know with clarity what they are believing when they believe (7). We are Christians because of what we believe about Christ. What we believe about Christ comes from Scripture. JTP not only provides historical insight into the development of the doctrine of Christ in the early church. It is thoroughly biblical as well. Deepening one’s understanding of the person and work of Christ, both from history and most importantly from Scripture, helps bring into focus more clearly what we believe about God and the gospel.

At a more academic level, recently there has been a renaissance of scholasticism and a rediscovery of Thomas Aquinas in certain Protestant academic circles. While mainly focused on theology proper, especially the Trinity, like the doctrine of the Trinity, Thomistic Christology flows through patristic Christology. The groundwork laid in the early church through the crucible of Christological controversy is foundational for Aquinas and his theological framework. The historical context for the Christological development that eventually blossoms with Aquinas is on full display in this book. Thus, JTP is beneficial for examining the historical framework for later Christological considerations. Yet even without an eye toward Thomism, the church historian will benefit from the exposé of an oft oversimplified dichotomy between Antioch and Alexandria, the close attention given to Cyril of Alexandria, and the distinction made between Chalcedon’s contribution and its primary emphasis.

Ware’s chapter on the atonement emphasizes the definite person of atonement as the Son of the Father (162, 170). This is a vital conclusion. However, Ware does not address the bearing his conclusions have upon the theology of atonement at large. Christology impacts atonement. Certain theories of atonement by necessity are deemed heretical since certain Christologies were condemned as heretical. Who dies on the cross informs what is done on and through the cross. While Ware discusses who does what work in salvation from a trinitarian perspective, more could have been said concerning what the triune God accomplished through God the Son on the cross.

Conclusion

Admittedly, as the cover says, this is an intermediate Christology. Introductory aspects of the historical narrative of Jesus of Nazareth are assumed so that more technical aspects of the Incarnation can be examined. A novice looking for beginning rudiments may be overwhelmed. Though not excessive, the Latin and Greek terms and phrases might deluge the beginner. Furthermore, the historical debates may also be a bit heady for the uninitiated. Therefore, these pages are not devoured quickly but require diligent, careful reading. However, for those seeking to deepen their understanding of the Son of God and better appreciate the triune God’s work in Christ, this book meets these aims.