The Gospel of Mark is understood by some as having a low Christology. This is understandable, to some extent, in light of the very human aspects of Jesus in the Gospel: he displays a range of emotions (Mark 1:41; 8:12; 3:5; 6:6); he doesn’t know everything God the Father knows (Mark 13:32; Edwards 2002, 13); he is occasionally unable to perform miracles (6:5); and his question to the rich man—“Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone” (Mk. 10:18)—could be interpreted as a direct denial of divinity.

Mark’s use of the Old Testament, however, reveals a Christology that is “enigmatic and paradoxical” (Strauss 2014, 734), full of the reality of Jesus’ humanity and yet pointing to his divinity. Jesus is the Davidic Messiah, and yet a suffering servant. He is the Danielic Son of Man who, at his lowest point, claims the highest authority (Mark 14:62). More than that, whether by direct quotation or by allusion, Jesus is revealed as the God of Israel who has come to bring salvation to his people.

These elements of Mark’s Christology will be demonstrated through analyses of his use of the OT: 1) in the prologue of the gospel; 2) in his use of titles for Jesus; 3) in Jesus’ performance of God’s activity; and 4) Jesus’ authoritative relationship with the Law.

The Prologue

The Prologue of Mark’s Gospel (Mark 1:1-13) sets a theological framework through which the rest of the Gospel is to be understood (France 2002, 54). The references to the Old Testament found in the prologue, in verses 2-3 and 10-11, hold a significant place in shaping the understanding of Jesus that Mark intended to communicate.

As it is written in Isaiah the prophet (Mark 1:2-3)

Following the incipit in 1:1, Mark opens his Gospel with a conflated quotation of Exodus 23:20, Malachi 3:1 and Isaiah 40:3. The three texts cited refer to God’s saving presence with his people. In Exodus 23:20, God promises to send an angel to bring the Israelites into the promised land. Malachi 3:1 refers to God’s messenger preparing the way for him to return in judgment on his people to purify them and make them righteous (Mal. 3:1-4). Isaiah 40:3 depicts God as returning as both warrior and shepherd (Isa 40:10-11; Watts 2000, 77), to comfort his people (Hays 2016, 24).

The Christological significance of the quotation is that God’s action in the Old Testament texts becomes Jesus’ action in Mark 1:2-3. Strauss (2014, 62) comments that in Mark’s use of Malachi 3, “‘my way’ becomes ‘your way’”. Similarly, France notes that the “substitution of αὐτοῦ for τοῦ θεοῦ ἡμῶν at the end [of the Isaiah citation]… allows the Christian reader to understand the κύριος of the previous line to refer to Jesus” (France 2002, 64). As Timothy Geddert (2015, 334) succinctly says, “In Jesus, Yhwh has arrived.”

A voice came from heaven (Mark 1:10-11)

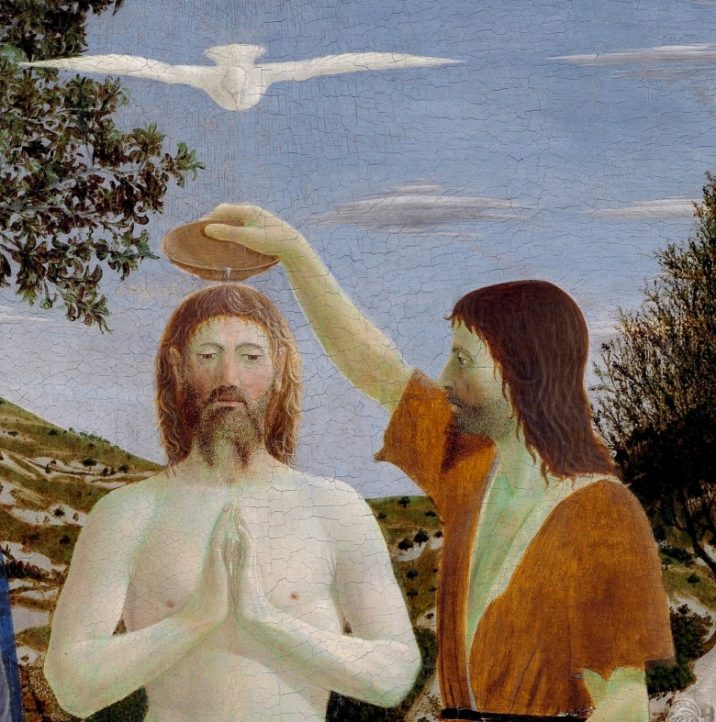

The second reference in the prologue is found in the voice that comes from heaven at Jesus’ baptism, saying, “You are my beloved son, with you I am well pleased” (Mark 1:11). This declaration is comprised of quotes from Psalm 2:7, Isaiah 42:1 and Genesis 22:2 (Boring 2006, 45). Psalm 2 is a Messianic enthronement psalm which focuses on God’s “son”, the king, reigning victoriously over his enemies (Geddert 2009, 112). The application of this psalm to Jesus identifies him clearly as the powerful and authoritative Davidic Messiah and Son of God (Ahearne-Kroll 2012, 48-49).

Isaiah 42:1, on the other hand, comes from the first Servant Song. Its immediate context concerns the Servant’s “divine endowment with the Spirit,” but the broader context of the Servant Songs includes “the climactic act of vicarious suffering and death” (Boring 2006, 45). The connection to Genesis 22:2 further develops this emphasis.The beloved son of Genesis 22 is Isaac whom God orders Abraham to sacrifice. Stephen Ahearne-Kroll (2012, 51) notes that “the ancient Jewish history of interpretation of the near sacrifice of Isaac sees him as a Son of God… obedient sacrificial victim of national importance… model of martyrdom… atoning sacrifice… and model of obedience… Any of these images could color the presentation of Jesus in Mark.”

Combining these two images of the victorious Son of God and the Servant/sacrifice, Mark foreshadows the sacrificial aspects of Jesus’ messiahship while the characters within Mark’s narrative do not fully understand until the cross and resurrection (Mark 8:27-33; 15:39; Strauss 2014, 73).

From the very beginning of his Gospel, Mark utilises Old Testament Scripture to set his Christological agenda. Jesus is not only identified as the agent of God’s saving work, but the Lord himself coming to his people for salvation and judgement. Jesus shares a unique relationship with the Father, and yet Mark begins to hint of the necessity of Jesus death for the fulfilment his saving plan.

The Titles of Jesus

A mere survey of the titles that Mark applies to Jesus is insufficient to ascertain their relevance to his Christology. It is the way that these titles are clarified through Mark’s narrative that reveals their significance (Boring 1999, 461; Bird 2005, 4). That being said, the way that Mark utilises Old Testament texts in relation to these titles shapes the readers understanding in a significant way.

Lord and Christ

Bird (2005, 12) observes that the titles “Christ” and “Son of Man” “form a mutually interpretive Christological spiral where one defines the meaning of the other.” There is also interplay between ‘Christ’ and ‘Lord’, particularly in Jesus’ question in the temple (12:35-36). He asks how the Christ can be the son of David when David himself, in Psalm 110:1, says, “The Lord said to my Lord, Sit at my right hand until I put your enemies under your feet.” The logic of the question depends on the assumption that a father would not call his son “Lord”, and yet David, in the Holy Spirit, calls the Christ, ostensibly his son, “Lord”. The solution is that simply being a physical descendant of David, receiving an earthly kingdom, is not a sufficient category for the Christ. While the Christ will be a physical descendant, he will be much more also (Edwards 2002, 377).

The usage of the term “Lord” in the verse that Jesus quotes points to the significantly heightened picture of the Messiah’s identity (Watts 2007, 318). Johansson (2010, 117) observes that verses 36-37 present the messianic Lord as more proximate to the Lord (the God of Israel) than to David. He continues later, “There is one κύριος, and yet two figures, God and Jesus, share this name and title” (Johansson 2010, 119). Johansson’s point helps make sense of the ambiguous use of “Lord” in other places in Mark, such as when after healing the demoniac, Jesus instructed the man to “tell them how much the Lord has done for you,” and the man proceeded to speak about “how much Jesus had done for him” (Mark 5:19-20).

This brief passage presents the Christ as both a human descendent of David and the divine Lord. While Mark does not explicitly use the categories of incarnation and pre-existence (Boring 1999, 470), the Christology of this passage certainly reflects them.

Son of God

The title “Son of God” is found in prominent points in Mark’s narrative: in the title (Mark 1:1), on the centurion’s lips at Jesus’ crucifixion (Mark 15:39), and by inference in the voice from heaven at Jesus’ baptism (Mark 1:11) and transfiguration (Mark 9:7). Jesus’ sonship to God the Father is clearly connected to Scripture also in the parable of the tenants (Mark 12:10-11) and in the link between the centurion’s declaration and Jesus’ cry of dereliction in Mark 15:39.

In the parable of the tenants, Jesus rebukes the Jewish leadership by presenting a narrative of God sending his servants and finally his “beloved son” only for them to be mistreated and killed by the leaders of his people (12:1-9). Jesus connects his parable to a quotation of Psalm 118:22-23, expressing the rejection and vindication of the stone/cornerstone. This tension between rejection and vindication encapsulates the Christological point that Jesus was making: even though he will be rejected and killed, he will be vindicated by God and become the beginning of the new Temple and people of God (Strauss 2014, 519-20).

While Jesus’ cry of dereliction (Mark 15:34), taken from Psalm 22:1, does not directly contain any mention of Jesus’ sonship, it is part of the scene that inspires the centurion’s identification of Jesus as “the Son of God” (Mark 15:39), and there are strong linguistic parallels with the baptism and transfiguration scenes (Bauckham 2008, 263-64). Jesus’ lamentation is real, because he is genuinely taking the place of sinful, rebellious and suffering people, but it also contains the hope of Psalm 22, that the one who is forsaken will be vindicated (Bauckham 2008, 259-60).

The “Son of God” then, as well as the Davidic king of Psalm 2:7, is the rejected and vindicated son of Psalm 118 and the forsaken and delivered “son” of Psalm 22. Mark presents the suffering and death of Jesus not as a contradiction of his sonship, but as the scripturally mandated path of the true Son of God. This is a complex image of a powerful and divine figure who at the same time is fully human, rejected and weak.

Son of Man

“Son of Man” is the title which Jesus most often uses for himself in Mark’s Gospel. It is clearly connected to his understanding of his authority (Mark 2:10, 28; 13:26; 14:62) and is the self-designation he uses when speaking of his impending suffering (Mark 8:31; 9:9, 12, 31; 10:33, 45; 14:21, 41). Simon Gathercole (2004, 368) notes that Mark frames the “Son of Man” in terms of Jesus’ “authority asserted, then rejected, but ultimately vindicated.”

The key Old Testament passage in view in the use of “Son of Man” is Daniel 7:13- 14, in which “one like a son of man” approaches the Ancient of Days and receives an everlasting, global kingdom. The “one like a son of man” in a way represents the “saints of the Most High” who suffer at the hands of the beasts but are also said to receive a kingdom (Dan 7:18, 25; Gathercole 2004, 370). However, Jesus does not adopt this terminology as a metaphor of the renewal of Israel as a nation- state; “it is he himself who is to receive that ultimate authority” (France 2002, 534).

The Markan Jesus regularly declares the link between the Son of Man and his imminent suffering. The central verse clarifying the purpose of his suffering is Mark 10:45, “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” This verse reverses one element of the Danielic image: where the Danielic son of man is served by “all peoples, nations and languages” (Dan 7:14), Jesus has come to serve, ultimately through his death on the cross (Boring 2006, 302).

The Danielic “Son of Man” imagery is strongest in the sayings which look forward to the future vindication, enthronement and judgement of Jesus (Mark 8:38; 13:26; 14:62). A number of interpretations about the timing of the events have been given. France (2002, 342, 535-36, 613) asserts that these verses refer to Jesus’ authority being “visible” through his resurrection, the growth of the church and the destruction of the temple. Adams (2005, 50-52) argues that they envision Jesus’ Parousia. It is perhaps possible to see elements of both; while the resurrection of Jesus and growth of the church is vindication and revelation of his authority, he will return to judge (Gathercole 2004, 371).

The key Christological point is made in Mark 14:62. Shortly before he is to be crucified, Jesus claims ultimate authority, even claiming again the name “I am.” Yes the Son of Man will suffer, but ultimately he will be vindicated and will receive an eternal kingdom and dominion. For the Markan Jesus, Jesus is that Son of Man.

Jesus Performing the Activity of God

Old Testament quotations are less numerous in the chapters between Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration. There are, however, allusions to Scripture within Jesus’ ministry that may not explicitly claim his divine identity, but certainly clue the reader in to Mark’s understanding of him. Some of these allusions show that Jesus performs the activity of God. Two examples of this are Jesus forgiving sins (Mark 2:1-12) and walking on water (Mark 6:45-52).

Forgiving Sins (2:1-12)

When the four men bring their paralytic friend to Jesus, he sees their faith and declares that the man’s sins are forgiven (Mark 2:5). This causes the scribes in the crowd to (internally) accuse him of blasphemy and question, “Who can forgive sins but God alone?” (Mark 2:7). Knowing their thoughts, he healed the man to prove his authority to forgive sins (Mark 2:8-11).

Jesus’ ability to perceive the attitudes of their “hearts” (Mark 2:6) is enough to hint at his divine attributes (Psa 44:21; Strauss 2014, 122), but the main contention in this passage is Jesus’ claim to authority to forgive sins. It has been argued that Jesus’ declaration of forgiveness is a priestly act (Broadhead 1992, 27), but this does not make sense of the scribes’ response. Their accusation of blasphemy shows that Jesus was claiming the prerogatives of God, because he is indeed the only one who can forgive sins (Exod 34:6-7; Isa 43:25; Edwards 2002, 78; Johansson 2011, 370; Leim 2013, 230).

Walking on Water (6:45-52)

Having sent the disciples ahead of him on a boat, Jesus came to them “walking on the sea” (Mark 6:48). This pericope has three significant allusions that present Jesus as YHWH. Firstly, the description of Jesus “walking on the sea” (περιπατῶν ἐπὶ τῆς θαλάσσης) echoes Job 9:8 in the Septuagint (περπατῶν… ἐπὶ θαλάσσῃ; rendered “trampled the waves of the sea” in the ESV) (Gathercole 2006, 63). Importantly, it is God “alone” who does this in Job 9:8.

Secondly, Jesus intended to “pass by them” (Mark 6:48). Numerous commentators identify a connection with God “passing by” and revealing himself to Moses and Elijah (Exod 33:18-22; 34:6; 1 Kgs 19:10-12; Garland 2015, 296-97; Geddert 2015, 333; Hays 2016, 72). This is heightened even further by the third allusion: the “implication of divine identity” (Gathercole 2006, 64) in Jesus’ declaration to his disciples, “I am” (Mark 6:50; ἐγώ εἰμι, rendered “It is I” in the ESV), which is likely an echo of God’s self-revelation in Exodus 3.

Jesus’ Authority in Relation to Scripture

A final aspect of the way that Mark’s use of the OT contributes to his Christology is the way that Jesus is positioned as authoritative over interpretation of the Scriptures. He makes authoritative declarations regarding the Sabbath (Mark 2:23-3:6), purity (Mark 7:1-15), dietary laws (Mark 7:17-23), divorce (Mark 10:1-12) and the greatest commandment (Mark 12:28-34) (Garland 2015, 308-312). A significant scene is found in Jesus’ interaction with the rich man regarding how to inherit eternal life (Mark 10:17-22). Even though he had fulfilled the commandments pertaining to human relationships, his money had been his real god. Geddert (2015, 328) argues that Jesus “calls him to abandon his false god and follow the true God, himself.” Jesus clearly places himself as the interpretational authority of Old Testament law.

Conclusion

In his Gospel, Mark utilises the Old Testament to enrich and explain the Christological significance of the story of Jesus. While he does not make explicit claims to Jesus’ divinity, such as those seen in John’s prologue, Mark’s use of the Old Testament pushes the reader to view Jesus in that way. Jesus is: the Davidic Messiah; the one doing the actions of God; the Danielic Son of Man receiving authority and reigning with the Most High; and as the Son who shares in the divine nature with the Father. Jesus does what only God is supposed to do and exercises his authority over the Law given by God.

This exalted picture of Jesus in Mark does not deny his humanity or his suffering. In fact, his rejection, suffering, forsakenness and death are all fulfilments of Old Testament Scripture, and are necessary for Jesus to fulfil God’s salvific plan and receive his full glory.

References

Ahearne-Kroll, Stephen P. 2012. “The Scripturally Complex Presentation of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark.” In Portraits of Jesus: Studies in Christology, edited by Susan E. Meyers, 45-67. WUNT. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Bauckham, Richard. 2008. “God’s Self-Identification with the Godforsaken: Exegesis and Theology.” In Jesus and the God of Israel: God Crucified and Other Studies on the New Testament’s Christology of Divine Identity, 254- 68. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Bird, Michael. 2005. “‘Jesus Is the Christ’: Messianic Apologetics in the Gospel of Mark.” RTR 64, no. 1: 1-14.

Boring, M. Eugene. 2006. Mark: A Commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Boring, M. Eugene. 1999. “Markan Christology: God-Language for Jesus?” NTS 45, no. 4: 451-71.

Broadhead, Edwin K. 1992. “Christology as Polemic and Apologetic: The Priestly Portrait of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark.” JSNT 47: 21-34.

Edwards, James R. 2002. The Gospel According to Mark. PNTC. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

France, R.T. 2002. The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek Text. NIGTC. Grand Rapids: Michigan: Eerdmans.

Garland, David E. 2015. A Theology of Mark’s Gospel. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Gathercole, Simon J. 2006. The Preexistent Son: Recovering the Christologies of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Gathercole, Simon J. 2004. “The Son of Man in Mark’s Gospel.” Expository Times 115: 366-72.

Geddert, Timothy J. 2015. “The Implied YHWH Christology of Mark’s Gospel: Mark’s Challenge to the Reader to ‘Connect the Dots’.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 25, no. 3: 325-40.

Geddert, Timothy J. 2009. “The Use of the Psalms in Mark.” Baptistic Theologies 1, no. 2: 109-24.

Hays, Richard B. 2016. Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels. Waco: Baylor.

Johansson, Daniel. 2011. “‘Who Can Forgive Sins but God Alone?’: Human and Angelic Agents, and Divine Forgiveness in Early Judaism.” JSNT 33, no. 4: 351-74.

Johansson, Daniel. 2010. “Kyrios in the Gospel of Mark.” JSNT 33, no. 1: 101-124.

Leim, Joshua E. 2013. “In the Glory of His Father: Intertextuality and the Apocalyptic Son of Man in the Gospel of Mark.” Journal of Theological Interpretation 7, no. 2: 213-32.

Marcus, Joel. 1992. The Way of the Lord: Christological Exegesis of the Old Testament in the Gospel of Mark. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press.

Strauss, Mark L. 2014. Mark. ZECNT. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Watts, Rikki E. 2007. “The Lord’s House and David’s Lord: The Psalms and Mark’s Perspective on Jesus and the Temple.” Biblical Interpretation 15: 307-322.

Watts, Rikki E. 2000. Isaiah’s New Exodus in Mark. Grand Rapids: Baker.