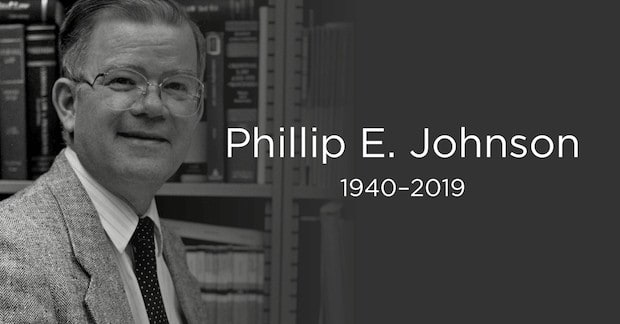

Phillip E. Johnson (1940–2019), sometimes called the “godfather of intelligent design,” died on November 1 at age 79.

Johnson, author of well-known books such as Darwin on Trial, became a formidable voice on creationism, science, reason, and faith. Johnson started his career as an attorney and scholar, and his books reveal how his legal training helped him craft logical and thoughtful arguments. Indeed, one of Johnson’s great legacies is teaching his readers how to ask better questions.

Below, you’ll find an excerpt on faith, science, and reason from Against All Gods: What’s Right and Wrong about the New Atheism, a book Johnson cowrote with John Mark Reynolds.

***

Scientists in particular have to be men or women of faith. Scientific research is a difficult and frequently discouraging enterprise in which success often comes, if at all, only after repeated failures. To be successful, scientists have to learn not to allow difficulties to destroy their confidence that success can eventually be achieved. This is faith of a kind, but in principle it is rational, because scientists know that scientists of the past have sometimes achieved success only after long years of frustration, when they were repeatedly tempted to give up and admit failure.

History teaches us that it is often reasonable to have faith in the ability of scientists to achieve seemingly impossible goals, and sometimes unreasonable to scoff at such faith. Yet there is a limit. Sometimes repeated failure is a sign that reaching a goal by the means one has been using truly is impossible, and to ignore that sign is madness, not faith.

. . .

If I were planning a course in reason and faith, the first thing I would want my students to understand is that it is wrong to assume that some people (e.g., the ones you find in church) rely on faith, whereas other people (e.g., the ones you would find in a laboratory) rely solely on reason. It would be much closer to the truth to say that everybody relies on faith and everybody reasons.

For example, many scientists today have an absolute faith in naturalism. Naturalism in this context is a philosophical doctrine that says that our universe is a closed system of natural causes and effects. On this assumption every natural phenomenon, like the origin of life, for example, is securely known to be explicable on the basis of natural causes accessible to scientific investigation—some combination of chemical laws and chance, to be more specific.

Scientific rationalists consider that the many successes of science fully justify them in holding this faith with absolute certainty. Indeed, they consider that faith in scientific naturalism is so thoroughly justified by reason that they do not think of it as a faith but as a defining example of reason.

The truth is that having the right kind of faith is not an alternative to reason, but an essential element of reason. That is why we can say to one another in argument, “You are not wrong to have faith, but you ought to place your faith in something more worthy.”

Communists had faith that their system would ultimately prevail despite its defects, because they had convinced themselves that history was on their side. They were not wrong to have faith, but they should have placed their faith in something more worthy.

. . .

Faith and religion are not the same thing; neither are reason and science (or logic). There is such a thing as reasonable faith and unreasonable science or logic. Paranoids, for example, are highly logical. It is just that they start from the misperception that they are the center of the world’s attention. Faith is a component of reason. We reason from principles. Even our adherence to logic is faith.