We are honored to have Drs. Peter Williams and Dirk Jongkind of Tyndale House, Cambridge, join us on theLAB to discuss the Tyndale House Edition of the Greek New Testament (THGNT).

Peter and Dirk, it’s a true honor to be able to speak with you both about this exciting and historic publication for many reasons, some of which I hope become apparent in our interview here on theLAB.

I remember flying back from SBL in San Antonio last November and walking by your seat, Peter, where you had a very large manuscript in your hands. When I glanced at the contents, I noticed that the entire document was printed in Greek. What struck me is that, throughout the duration of that entire ten-hour flight back to the UK (a red-eye no less!), you never watched a movie, you never shut off your overhead light, and I don’t recall you ever visiting the bathroom. You studiously edited that manuscript (a later draft of the THGNT, as it happens) for many hours.

That is amazing endurance, and it speaks to the importance of this project for you, Peter— and I’m sure Dirk’s commitment has been just as enthusiastic. This is a good place to begin our interview questions:

Could you both comment on what the THGNT represents to you in terms of its significance to yourselves as biblical scholars, to Tyndale House as a center of evangelical scholarship, and to the church as a whole?

Peter Williams: It has been hugely enjoyable being involved in the preparation of THGNT and it has also been a great privilege. So much has been facilitated by living at a period in history when there is an abundance of textual information online and by being in a location that supports and resources biblical scholarship. I have learned a lot through the editorial task and in particular through the process of having to address so many individual editorial decisions.

Dirk Jongkind: There are only so many things you can do in life, and this project has taken up most of the last decade. Of course it is a big thing for me. It has kept me out of the publication mill for these years, but at the same time has given me the opportunity to look into the details of the text in a way few other projects would have. Tyndale House exists to promote biblical scholarship at the highest possible level—by means of providing a research library, by means of being a research community and the Tyndale Fellowship, by means of providing the tools for others to work with. This project is another such tool: I hope it will help folk to read and understand the New Testament better than before.

For what reasons would a pastor, scholar, or student want to pick the THGNT off the shelf for their study of a NT passage rather than any number of other editions currently available? Or should the Tyndale House edition be used in conjunction with other standard texts? To ask the question another way, is there a specific use case in mind for the THGNT, or would you consider it a specialty text of sorts? For example, the NA28 is a text critic’s tool; UBS5 is for translators; RP2005 and the SBLGNT might be considered “specialty texts.” Does the THGNT fill a niche in the “market”?

Peter Williams: I think there are many advantages to the THGNT, but it is not meant to displace other editions. We have sought to design the whole edition in a way accountable to the earliest witness at each point. Thus readers can know that the text at any point in the edition is based on multiple witnesses and, outside of Revelation, at least two witnesses from the fifth century or earlier.

Likewise we’ve sought to following early paragraph marks and spellings and even early breathings and accents (though these are not as early as the other features. NA28 has many great features we lack: cross references, lists of citations, and more details of manuscripts, to name just a few. Thus I think scholars will need both ours and the NA editions.

On the subject of citations and paragraphing we have different philosophies. We have adopted a minimally interpreted text. Our main text is clean of editorial signs, except verse numbers. That’s great for interpreting without preconception. NA28 defines the boundaries of quotations with italic font. That’s helpful if you want to find quotations quickly, but less good if you are determined not to let others predetermine your interpretation. There’s surely place for both. Through preparing the edition and finding that so many alleged “quotations” are accentually integrated within the manuscripts in which they occur (preceded by final grave accents and with no punctuation preceding) I came to the view that the problem with marking quotations distinctly is that it can create too much of a dichotomy between what is a short quotation and what isn’t, in a way which may lead to anachronistic thinking.

Dirk Jongkind: Personally, I wanted to have the best possible text available in a form where the critical apparatus does not distract me. I wanted a good text designed for reading that feels like a Bible instead of a critical text, one I can take to church. At the same time, the THGNT is a text that asks us questions—because we see the text in a shape that, in some aspects, is more like older times than the 21st century. And that is very helpful for any serious student of the New Testament.

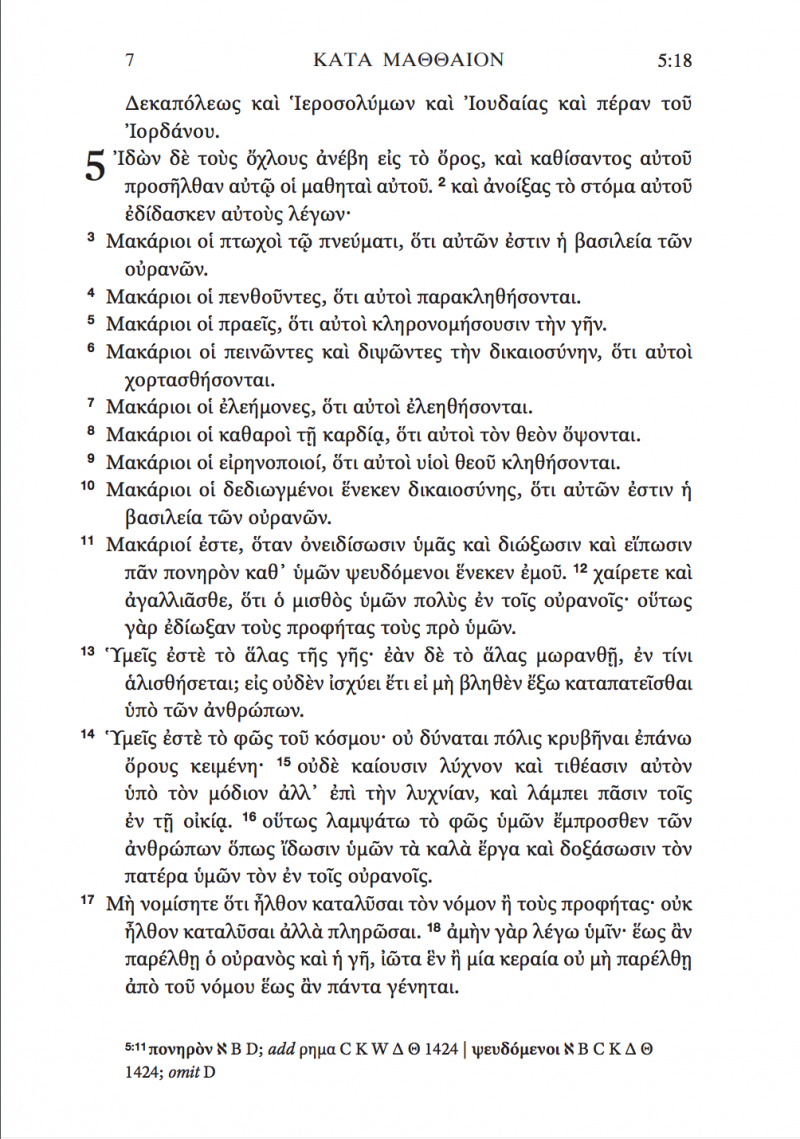

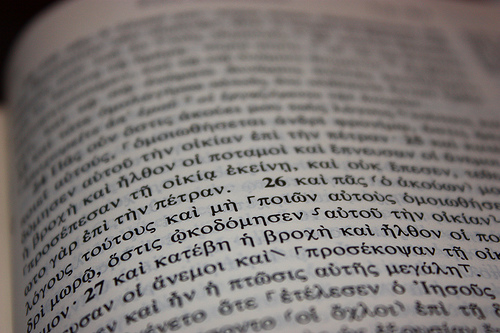

Here’s an example from Matthew (a fuller 12-page PDF is accessible here):

It’s been said that this edition focuses on scribal habits in a way that other critical editions don’t. Can you provide a few examples where your focus on scribal habits leads to a different reading than other critical editions? What, ultimately, is the import of the scribal habits that you and Peter Head have identified? Do you have categories for these scribal habits, described in the introduction to the THGNT? Furthermore, are there other emphases apart from scribal habits current in text-criticism that may warrant the production of future editions or revisions by Tyndale House?

Peter Williams: I don’t have anything to add to what Dirk will say, other than in the case of spelling. I took a great interest in spelling and we certainly see that some manuscripts have tendencies to prefer certain spellings, but occasionally they appear to ‘let through’ spellings against their own habit. When they did this we gave greater weight to that testimony.

Dirk Jongkind: This question is too big to answer in an interview and for a full answer you will have to wait for the monograph length introduction (which is some years away, don’t hold your hopes up yet). But the whole notion of harmonisation is one of the main reasons why a text grows over time. When there is a longer text but no obvious reason for harmonisation and no reason to believe this is part of some sort of editorial activity, a good case exists for that reading. That is one of the reasons why we have the words ‘and fasting’ in Mark 9:29.

How many different disciplines were involved in this edition of the GNT? Was this a text-critic only exercise, or were theologians and NT scholars of various specialties also part of the effort?

Peter Williams: We sent our complete draft both to textual critics and those who specialise more in exegesis, but in many ways we have actually tried to restrict exegetical considerations. We have not assumed that scribes regularly sought to impose their exegesis in the copying process. The main way theology has been involved has been actually as a driving force. The whole edition was conceived as an exercise in methodological conservatism towards the documents. Having a strong view of our own sinfulness and fallibility, as well as of the fallibility of individual scribes, we’ve sought to restrain editorial choice by insisting on multiple attestation. We also wished to make the edition one which focussed on the main text and encouraged reading of it. That’s why we have put most of the introductory material at the back of the volume, following the text.

What were some of the most difficult textual decisions you faced? How did you resolve them in ways that might differ from other modern editions of the GNT?

Peter Williams: The ending of Mark and the Pericope Adulterae in John are significant issues. We wanted to focus attention on the manuscripts and also highlight the very different levels of attestation these two passages have. Mark 16:9-20 are omitted by our two weightiest Greek manuscripts, but have circulated as part of the gospel since at least the time of Irenaeus and are present in almost all other Greek manuscripts. The Pericope Adulterae has much weaker attestation and in the entire first millennium is more often omitted than included.

As editors, we were also looking to avoid having brackets in the main text. We’d studiously limited the use of editorial signs to just four forms of punctuation and the verse numbers as features that came between letter sequences. We wanted to stay minimal.

Another tough decision was whether to include question marks. Of the four sorts of punctuation we’ve allowed (full stop, comma, raised dot and question mark), the question mark is the only one to post-date the NT, occurring most of a millennium after the NT was written. Arguably the existence of question marks throws up all sorts of problems and anachronisms that our edition has been trying to avoid. However, we still have not undertaken a review of the entire system of NT punctuation and until that has been done, removing these signs upon which so many readers rely is difficult.

Dirk Jongkind: Perhaps the most confusing variant is Matthew 15:30 and the order of the terms the lame, the mute, the blind, and the crippled. There are at least eight permutations in word order attested, and none of these seem to show clear influence from the next verse. Rather than picking a preferred manuscript, we looked at overall spread: which word is first in most orders that have also early attestation, which is last?

I noticed that your edition is listed at 540 pages long, whilst the NA28 entails nearly 900 pages. Why the difference in length, apart from the dual German/English introductions?

Peter Williams: I haven’t done all of the measurements to work this out, but our edition will have much less front and back matter. In addition our apparatus is smaller and there are significantly fewer paragraph divisions. We don’t set apart quotations and poetic lines.

You decided to keep numerous spelling errors in the text, as found in the ancient manuscripts (i.e. Acts 10:15) Why is this important to show modern readers, rather than correct the text at those places?

Peter Williams: I would reject the idea that we are keeping numerous spelling mistakes. Rather, our edition is in Koine spelling. What often people today might call a spelling mistake was clearly not thought of as one by educated Koine scribes. Any unconventional spelling we adopt should be attested in a minimum of two manuscripts from the fifth century before and must also display a wider pattern of attestation that shows it was conventional. One reason we’ve preserved these Koine spellings is because it is quite clear that early NT manuscripts partially preserve a distinction between the long and short /i/ in spelling.

Now I’m not claiming necessarily that we know that people pronounced this distinction, but at least there are some very strong correlations between particular spellings and etymological vowel length making it probable that some people sometimes made the distinction and that at least this was sometimes reflected in historical spelling until the fifth century AD. When, for instance, in Luke 10:54 all our earliest witnesses (P45 P75 Sinaiticus A B D W) write γεινεται not γινεται and we know this also fits into a wider pattern of the way those manuscripts spell etymological long /i/ in Luke for this lexeme and others, what possible reason does an editor have for writing γινεται other than their own ignorance of ancient spelling conventions or prejudice based on the way they were taught Greek? In a case like this, as editors seeking to make an edition based on the earliest documents, we didn’t feel we had a choice. Of course, there were much harder cases, but the decision to adopt spellings which are non-standard in the printing era but were perfectly standard in the Koine era just flowed naturally from our initial decision to bind ourselves to early witnesses.

When I first started working on the spelling review of the entire NT, trying not to take the spelling of a single lexeme for granted, I initially thought the spelling we would arrive at would be much more divergent from other editions than it in fact was. However, over time I came to see that the application of a few editorial constraints relating to multiple attestation, or what we internally called the 2+ rule (a minimum of two early manuscripts everywhere within a book or section have to show the spelling and it needs to have signs of wider attestation) brought our spelling closer to that of other editions. In spelling we look like a much stronger version of Westcott and Hort, but when Drayton Benner of Miklal software finally calculated our level of affinity to various editions, he concluded that we were closest to NA27 (As I’ve written elsewhere, NA28 doesn’t spell as well as NA27).

Dirk, you mention on the blog devoted to the THGNT the importance of considering an “ideal” text, i.e. “the text of the ‘work’ as it was produced in the first place,” and the theology of it all (I’m assuming you mean the theology behind the production of NT “scripture”). Could you both elaborate more on the relationship between the two, whether there is a disjuncture at this point that students of the text must be able to articulate and resolve?

Dirk Jongkind: I believe there is such a thing as the ‘theology of textual criticism’, just as there is a theology of any human enterprise or faith-related phenomenon (just as there is a philosophical reflection on all these things). I am sure that in the future I would like to say something more about how theology shapes the activity of ‘doing textual criticism’ and I have found Tregelles quite helpful in this regard. I don’t think, though, that theology precedes textual criticism, but rather that it follows from the text. It is safe to say that one of my motivations to be concerned with the details is that I believe the details of the New Testament matter.

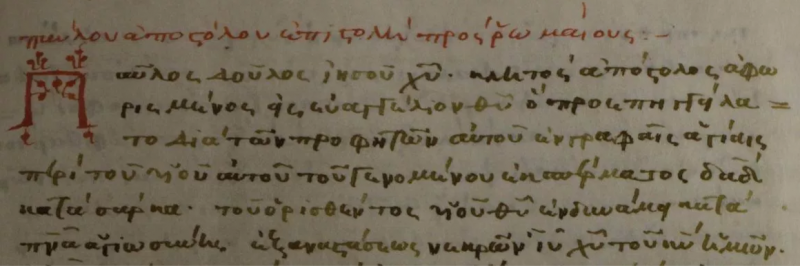

Your choice of Tregelles as the point of departure for the THGNT is an interesting one, given the history of Tregelles’ text. Can you explain more about the process of building the THGNT text-from from Tregelles, and what challenges this presented to you as editor(s)?

Peter Williams: Tregelles was very interested in ancient documentation and also had a very high view of the text as sacred scripture. We agreed with him in both of these matters and, as we also felt that his edition had been unjustifiably ignored, it was a simple decision for us to start with his edition. It also enabled us to save a lot of time in the editorial task, just in simple things like punctuation decisions. Initially we were thinking that our revision would be quite light. It ended up being much more thoroughgoing, including in the area of punctuation.

Was Crossway a natural fit as the print publisher for THGNT, given the relationship between Tyndale House and Crossway in the production and publication of the ESV? Or were there other factors involved that pointed to Crossway as the best choice?

Peter Williams: I absolutely love the beauty of things which Crossway produces. They really want their printed Bibles to be art forms. I don’t know of any evangelical publisher that puts as much emphasis as they do on the quality of the physical printed copy. I’m sure that when readers see these Bibles, which will be printed by L.E.G.O. in Italy, they will agree that they are aesthetically pleasing. Through the ESV, Crossway also have a great relationship with our local publishers, Cambridge University Press, and we’re glad that CUP will also be producing their own edition.

For more on the THGNT, see

P.J. Williams, “The Greek New Testament, Produced at Tyndale House.” Early Christianity 8 (2017): 277-81.

Dirk Jongkind, An Introduction to the Greek New Testament (Crossway, 2019).

Mark Ward, “Review: An Introduction to the Greek New Testament Produced at Tyndale House, Cambridge” (Word by Word, June 12, 2019).