We have the immense privilege of interviewing Jonathan T. Pennington here on theLAB concerning his recent book, The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing, available now on the Logos digital library. This book was one of the highest-rated Christian books of 2017 by numerous reviewers, and for good reason: it is academically rigorous, eminently readable, and delightfully devotional. Jonathan includes a number of small but helpful schematics throughout the book that have stuck with me since, and some have found their way into my journal as reminders of how to think of Jesus’ most beloved and memorable teaching from the Gospels. Enjoy the interview, and be sure to get a copy of the book today.

1. Can you give us some of the background to your interest in the Sermon on the Mount, and what led you to finally write this book?

I’ve had the privilege of studying and writing and teaching on the Gospel of Matthew for many years now. Sooner or later, all Matthew scholars end up being drawn into the beautiful and complex world of studying the Sermon. This happened to me too. About 10 years ago I started teaching a class on the Sermon at Southern and quickly realized I didn’t know anything about it! So I started studying and that led me to reading in virtue ethics and the history of interpretation. Eventually I realized—largely at the spurring of many students—that I should write down some of my thoughts. I’m a slow writer so it took me five years, but I eventually got it done!

2. You state early on that your desire for the book is to equip readers of all sorts with a “reading strategy and overall integrated theological interpretation” for the Sermon (p. 2). Can you give us a preview of what that strategy is and how it can equip both scholars and laypeople to read the Sermon theologically?

When you begin to study the Sermon it becomes clear very quickly that the landscape of how it has been read by all sorts of people throughout history is both large and diverse. Reading the Sermon well is not easy because it is such a masterpiece in the midst of a master work (the Gospel of Matthew), integrated into a larger canonical matrix (the whole Bible). Through years of studying and teaching I came to see how it fits together in a particular way. I wanted to offer that so readers could make sense of the whole rather than just dipping into parts of the Sermon as we often do. Even many commentators never seem to consider how the whole Sermon fits together, but instead present helpful tree‐ and leaf‐level interpretations; I wanted to also offer a forest‐level vision.

In short, I think the Sermon is a piece of wisdom teaching (paraenesis or protrepsis) from Jesus that invites people into true human flourishing through wholeness centered on God and his coming kingdom. Jesus’ Sermon invites us to see the world in a certain way and to be in the world in a certain way that accords with God’s nature, will, and coming reign upon the earth; in short, “righteousness” (cf. Matt 5:20). It is a call to faith‐based discipleship in Jesus, the Son of God.

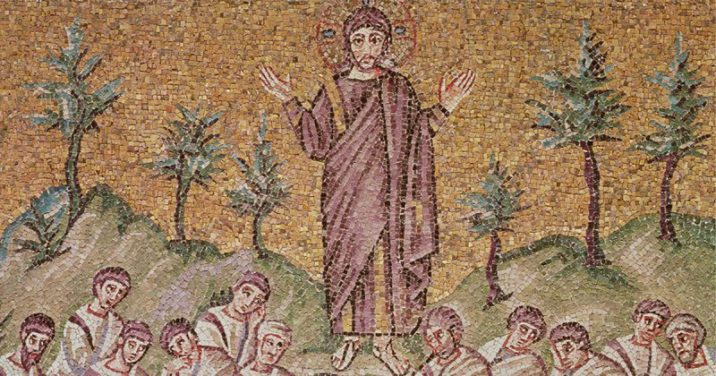

I think that once we see this whole vision it provides a framework to understand the many parts and pieces of the beautiful mosaic that is the Sermon. This is far more than providing historical background or literary structure (both of which are important and which I utilize). It is a theological vision for the life of discipleship.

3. You make the interesting statement that the Sermon is a good “litmus test” of one’s theological commitments (pp. 3-4). How is that so?

The key is to spend some time in the glorious 2000-year history of the interpretation of the Sermon – and there’s a lot of it! What you will find is that differences in denominations and theological practices and traditions can often be traced back to various ways people have interpreted the Sermon.

For example, take just the 16th century in Germany. Luther’s reading of the Sermon was crucial in his break with the monastic tradition in emphasizing that the Sermon was for everyone, not like the monks thought, who took the Sermon as part of the “evangelical counsels” (not required for everyone but only for those desiring to be “perfect”) rather than the precepts (required for everyone). The whole Bible is for all. At the same time, the Sermon’s high demands are part of the “Law” aspect of the Bible, showing people that they need the gospel. This is different from the Reformed tradition which would instead understand the Sermon in the category of the “third use of the law.” Luther also vehemently disagreed on the other side with the Anabaptists/Mennonites who took their marching orders of non-violence, non-oath-taking, etc. directly from their literal reading of the Sermon. Against this way of thinking, Luther argued for the Two Kingdoms approach that saw the Sermon as something that people must obey as individuals but not as a rule for society, where we must keep order.

We could look at many other examples as well. The point of the litmus test idea is that because the Sermon is so rich theologically, addressing so many different issues, and because it has been so influential, one can often dip a theologian or reader into it and tell a lot about their views on different issues.

4. Can you explain how Jesus’ presentation of a “Christocentric, flourishing-oriented, kingdom-awaiting, eschatological wisdom exhortation” in the Sermon relates to an “aretegenic” purpose for the Sermon as a whole?

That is a mouthful, isn’t it!

Every part of that definition is important (Christocentric, flourishing, kingdom, eschatological) and it comes down to the “wisdom exhortation” part. Again, the Sermon is a piece of wisdom literature or better, protrepsis/paraenesis, a form of rhetoric very common among philosophers and sages in the ancient world (Jewish and Greco-Roman). It is what teachers did when they wanted to call people to adopt a particular vision of virue (arete) that promises the flourishing we all long for. Jesus’ teaching regarding what this virtuous life looks like is as unique as he himself is – it is shocking and upending and beautiful and true, rooted in who God is and promising eternal life with him.

5. I personally found your framing of the Sermon in mountaineering terminology visually stimulating, including your discussion of the “base camp” for any reading of the Sermon, where you set forth Umberto Eco as a formidable guide for one’s ascent (pp. 19-24). What is it about Umberto that makes him such a reliable resource to the Sermon?

It doesn’t have to be Eco, certainly, but like many others, I have found him helpful in thinking about how language and culture and texts interact in the mysterious event of reading.

I utilize Eco’s idea of the “cultural encyclopaedia” to help us understand the complex world in which early Christianity finds itself – simultaneously heir of the great tradition of Israel and its twists and turns in Second Temple Judaism while being situated in the Roman Empire, complete with its own roots in Greek philosophy. My point is that understanding this cultural and linguistic situatedness provides help in our interpretation of the Sermon.

6. Why, in your discussion of makarios, frequently translated as “blessing,” do you consider Psalm 1 significant to our understanding of what Jesus intends by the term (pp. 51-54)?

Psalm 1 is a wisdom psalm, and like many other places in the Bible (and other ancient literature), it uses a term to describe the state of human flourishing that comes from living a certain way. That concept is expressed in Hebrew with the term ashrē and in Greek with makarios. In Latin it is beatus, whence our word “beatitudes” comes. All of this is distinguished from a related but different concept of “blessing,” which describes the divine activity of bringing life. The big problem is, as I spend a chapter showing, that while every other language I’m aware of distinguishes clearly these two ideas, in current English we do not, instead translating them both with “blessed,” hence creating potential confusion for English interpreters.

Psalm 1 is helpful because it is the easiest direct parallel to what is happening in the Beatitudes (Matt 5:3-12) – both are invitational exhortations to redirect one’s thinking and habits towards God’s revelation because this alone promises true human flourishing.

7. What is your hope for the legacy of your book in the life of the church and the future of biblical studies?

In a time when countless books are published, I’m honored already by how many people have taken the time to read the book and to share with me how it has helped them personally as well as in their teaching and preaching of the Sermon. I certainly hope that some of my arguments will influence the academic interpretation of issues within the Sermon, but far more important is having an impact on individuals and the Church to grow as followers of Jesus the Lord.

Jonathan T. Pennington (PhD University of St. Andrews, Scotland) is assistant professor of New Testament Interpretation at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

Jonathan has also produced a couple of excellent Mobile Ed courses for Logos, including one specifically on the Sermon. Be sure to check out both the 4-hour The Gospels as Ancient Biography: A Theological and Historical Perspective (NT301) and his 5-hour course, The Sermon on the Mount (NT251).