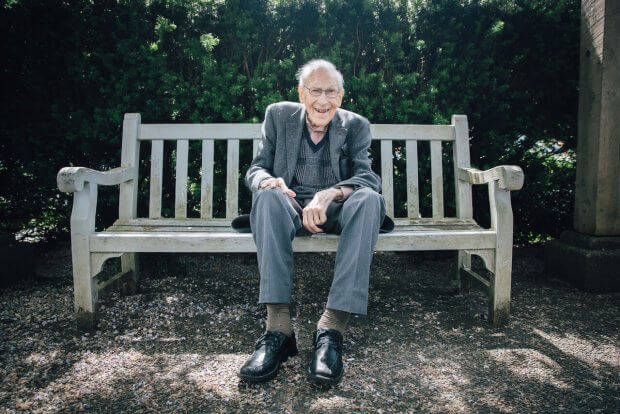

Today, J. I. Packer entered glory at age 93.

Born in England in 1926, his life was not without difficulty, beginning with an accident that left him with a hole in his skull. After coming to faith in college, he dedicated his life to Christian ministry—which resulted in decades of teaching, dozens of books, and a lifetime of faithfulness.

A few years ago, our team sat down with Dr. Packer to film his testimony and message about the importance and benefits of knowing—and being known by—God.

Dr. Packer was asked one question he had to think about: “When you ask how I would like to be best remembered, you put me on the skids, because my life and my ministry honestly have been focused on the Lord and on his people and on folk who one hopes will one day become his people. And I’ve never, under ordinary circumstances, spent time reflecting on myself at all. Not in that way. I think and I hope that I’m not kidding myself about that. . . . I think I want to be remembered simply as a voice: a voice for the Bible, a voice for God, a voice for the gospel, a voice for the faithful Church, a voice for Christian outreach, and a voice for spiritual maturity within the congregation.”

Watch the film trailer below, or watch the entire film here.

The following article is excerpted from the January–February 2019 issue of Bible Study Magazine.

***

The Catechism of Knowing God

By Rebecca Brant and Jessi Strong

Among the millions of books that have been written through the ages, those that endure we call “classics.” From Plato’s The Republic and Thoreau’s Walden to Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Twain’s Huckleberry Finn — these are the volumes that make the lists of books everyone should read. Among Christian titles, Knowing God by J. I. Packer ranks in the top 50 books that have been most influential in shaping evangelical beliefs. In fact, it makes the top five.

Knowing God has sold more than 1 million copies and has been translated into more than 20 languages. As Packer explains, “It’s a book that you can use at a very early stage of Christian interest, and it’s a discipling book. It gets readers to the point where one hopes that they are thoroughly committed to God on the basis of all the relevant biblical knowledge.”

Initially, Packer didn’t set out to write a book. He was recruited by the editor of the now-defunct Evangelical Magazine to “fill a gap,” he recalls. “She said to me one day, ‘Look, we haven’t got anything on God that we can put into the hands of inquirers. We’ve got lots of good stuff on godliness—we’re building up resources there. But surely “good nurture” means that we ought to focus directly on God as well as the other things. Will you write a set of articles?’ And so I began.”

God’s providence

Packer was well along God’s path for his life by that point—a path that began with a life-altering accident. As a schoolboy of 7, Packer was chased by another boy into the street, where he was hit by a passing truck. His skull was badly fractured. Packer recalls, “The effect was like hitting an eggshell with a spoon when you want to open the top to eat the egg.” A local surgeon who had recently trained in Vienna (the world leader in brain surgery at the time) was able to operate, but even with the surgeon’s providential skill, Packer was left with a hole in his skull—a vulnerability that precluded him from his peers’ active pursuits.

That early accident and his long recovery gave Packer plenty of time to develop a love of reading. He recalls hinting strongly to his parents that he wanted a bicycle for his 11th birthday, but considering the possible dangers after his earlier trauma, they opted for a typewriter. “I think that was very good parenting on their part,” he now says. His life’s direction toward academia was further sealed when, at age 18, he registered for the armed forces and didn’t make it past the physical examination. “So I was on to university as I would have been in peacetime.”

In his first two weeks at the University of Oxford, Packer had a spiritual revelation. He had grown up in a family that attended church more from routine than from conviction. “What hadn’t registered is that the Christian faith—the truth—is not something that you keep at arm’s length. It’s something that you live by.”

But just 10 days after beginning his studies, Packer attended an InterVarsity event. He was bored by the sermon, he said, until the elderly clergyman began describing his own conversion. “And quite suddenly everything came clear to me, because he was talking about a personal relationship with the Lord Jesus, which I hadn’t got,” he says. “By the end of the sermon, the way that I felt it, the Lord Jesus himself was breaking into my life and was calling for a personal response from me.”

Within two years Packer knew he was called to pastoral ministry, “and everything else followed from that, I could fairly say, in a straightforward manner.”

A life’s calling

Toward the end of his university career, the principal of a seminary in London contacted Packer about teaching Latin and Greek. It was meant to fill the gap between the loss of one instructor and the hiring of another. “I incidentally found that I was a teacher by nature,” he says. “Nobody ever needed to teach me how to teach.”

Now retired, Packer filled a number of roles over his long career—curate, lecturer, librarian, and principal—before taking up his longest-serving position as professor of theology at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia. He served there from 1979 until his retirement in 2016. But Packer’s early approach to teaching still influences how he views the discipline today, and that echoes the organization of his seminal work, Knowing God: “Already, in my early 20s, I was thinking in terms of catechism—teaching the basic elements in a full-scale topical grasp of the faith by which you live. Whereas in the Bible everything is angled and part of a scheme of its own, in catechism everything is angled on the ignorant individual and the doctrines or the principles of the practice.”

A book in the making

When Packer began, in the 1950s, to write the articles that became the manuscript for Knowing God, he imagined his ideal reader: “I have a fairly lively imagination, and I thought of a man or woman, middle 20s, professional, competent, businesslike, not impressed by verbiage, not impressed by wandering thoughts, but ready to listen if anybody has got anything serious and focused to say to them. This was right after the Second World War, when everybody was trying to settle down and establish themselves.”

Packer then asked himself what he would say to his imagined reader. The first chapter of Knowing God, he explains, “is to the effect that focusing on God is worthwhile, and this is why.” Each chapter was an answer to Packer’s question of what to tell his reader next—a presentation he describes, in the book’s 1973 preface, as “a string of beads: a series of small studies of great subjects … conceived as separate messages but now presented together because they seem to coalesce into a single message about God and our living.”

The book is arranged in three sections: “Know the Lord” goes into specifics of knowing and being known by God—or more importantly, for Packer, knowing about God and actually knowing God. “Behold Your God!” offers meditations on the attributes of God, including wisdom, love, grace, jealousy, and wrath, among others. “If God Be for Us” applies the wisdom of previous chapters to answer what it means to be a Christian and live the Christian life.

Returning to his vision of a catechism, Packer says, “I’m building up, you see, a concept of a relationship with God which is cognitive, and obediential, and submissive and affirmative. I’m trying to build up a coherent knowledge of God that’s as broad and deep and high as the Scriptures.”

Packer was initially concerned that the writing might be too compressed, too heavy for his ideal readers. “Well, it didn’t prove too heavy for a popular audience after all. It’s become a discipling book for Christians around the world. So I’m amazed and humbled and very thankful.”

Knowing God in life

When Packer ruminates on knowing God in his personal life, he likens it to the way we might interact with the mind of a great artist through their work. “I value the form of expression [in El Greco’s work], which allows me to affirm that I know El Greco fairly well, although, he died in the sixteenth century. He was an idiosyncratic genius whose work I find marvelously stimulating and invigorating. Especially his Bible scenes.”

Packer finds that his study and experience of the artist’s work allows him to see inside of the man himself. Getting deeply acquainted with his material gives one insight into his personal convictions. “I want to know what makes the person who produced the material tick, whether he’s a Bible writer, or El Greco, or Charles Dickens, or somebody else. I’m not interested in the work without being interested in the person. What’s driving John as he puts together the various chapters of his Gospel? What’s driving Paul when he writes the way he does to the Colossians?”

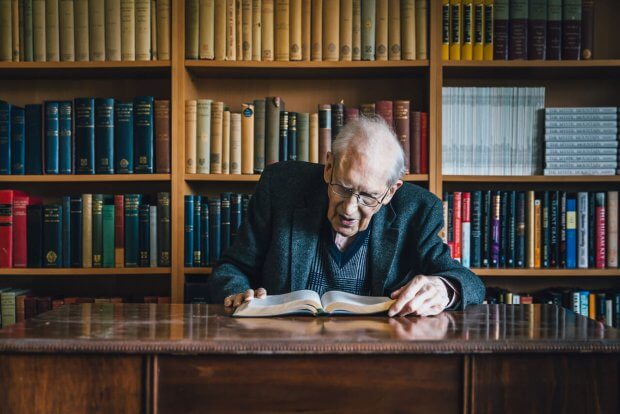

Knowing God through his Word

Now in his 90s and coping with macular degeneration, Packer still reads the Bible daily, with the aid of a magnifying glass. “There are people who always use the same method. But my mind has always roved—wandered with a purpose—through Scripture chapter by chapter, section by section. When I’ve read a text in its broad context a number of times, I make notes on its themes and thrust, and I try to make the notes as tidy and memorable as possible,” he says. “I’ve tried to read the whole Bible once, at least, every year. And I want to read the Gospels a good deal more than once a year. I do find, again and again, that passages come to life when I read them aloud, in a way which they didn’t do when I read them silently. Then I try to make sure that I can see how the book that I’m reading holds together paragraph by paragraph, chapter by chapter, theme by theme.”

Although his study of the Bible spans nearly three-quarters of a century, Packer continues to find new insights and fresh approaches for teaching. In recent months, he has returned to meditations on the kingdom of God, “which is the kingdom of Christ,” he says. “It’s been, from the first moment, his kingdom in which he has a dual control. He prescribes what should happen to the various rational creatures in the kingdom—and through those creatures—and he controls what does happen. You have both senses of the word ‘control’ together, as a matter of fact, in the Lord’s prayer. That has always struck me as significant. ‘May your kingdom come’—that’s kingdom in the sense of obedience to the Creator’s word. And ‘yours is the kingdom’— you’re in control—just as ‘yours is the power and the glory.’ ”

Ever the teacher, Packer returns to structuring his thoughts, if not strictly as a catechism, as an instructional order. “In the Bible, you have the promised kingdom of Christ, and that is the theme, in different ways, all the way up to the end of the Old Testament. And then you have the present unfinished kingdom of Christ, which, in a few places, is spelled out explicitly in terms of the contrast between the kingdom of Jesus the incarnate Lord in first-century Palestine and then the kingdom as it has been since the resurrection. And that is the kingdom in which, from his throne as the risen Lord, Jesus, on the Father’s behalf, controls everything.

“Peter gives you the most explicit and the briefest statement when he tells Cornelius, at his first mention of Jesus: ‘He is Lord of all.’ ”

This article is based on interviews conducted by Faithlife TV and Scott Lindsey; photographs are by Ben Bender.