Christians understand the meaning of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem . . . but there’s so much that’s hazy in our imagination and understanding of the details.

Popular Christmas songs, Christmas movies, and Christmas media have given us the wrong idea.

Read about the fascinating truth in this excerpt adapted from the Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Gospels.

***

The geographical setting of Bethlehem

The ancient village of Bethlehem was located five miles (eight km) south of Jerusalem, one half mile (0.8 km) east of the watershed at the end of a short, narrow spur of chalky limestone angling southeastward. Its elevation, at just over 2500 feet (762 m), is about the same as Jerusalem, and the rainfall is virtually identical for Bethlehem and Jerusalem (twenty-four in, or sixty-one cm, per year, about the same as the wheat fields from central Nebraska to central Texas).

The end of the spur on which ancient Bethlehem sat falls away quickly to the east, to the Beit Sahour basin. Here are wide tracts of land and rich, fertile fields suitable for grain. The soils of the Beit Sahour basin are a nice mixture of red clay (terra rosa) and softer, somewhat chalky rendzinas—a combination that ensures adequate nutrients and soil that can easily be plowed.

Just beyond, where rainfall amounts drop below the twelve-inch (thirty cm) annual minimum necessary for wheat, the soils are immature and unproductive and the overall shape of the land morphs into the chalky, barren Wilderness of Judah. With it, permanent settlement gives way to transient encampments of sheep and goats as shepherds follow the seasons in search of watering holes and grazing land (compare Pss 23:2; 65:11–13).

For the residents of Jerusalem, the view into this eastern wilderness is largely blocked by the Mount of Olives, a geographical reality that tends to isolate Jerusalem from its larger environment.

Bethlehem has no Mount of Olives-type ridge to the east, and the view afforded its residents is a wide open downward expanse, over the wheat fields of the Beit Sahour basin and into the pallid, undulating hills of the Judean Wilderness. This topography tends to associate Bethlehem with the natural environment of shepherds, even though the village itself sits high in the fertile hill country of Judea.

All textual and archaeological evidence—which is scant—indicates that the Bethlehem of the Old and the New Testaments was but a village.

Very little archaeological work has been done at the site except in connection with the Church of the Nativity. The oldest settlement seems to have been east of the biblical town in the Beit Sahour basin. Only with the advent of cistern technology in the Iron Age did settlement move to the top of the ridge now occupied by the Church of the Nativity and Manger Square. This is an area that otherwise lacks natural sources of water and where settlement is somewhat restricted by a topography which drops away to the east, north, and south.

Rehoboam, the son of Solomon, strengthened Bethlehem’s fortifications (2 Chr 11:5–6), but to what extent is unknown, and nothing indicating city walls from his time has been found.

Bethlehem enjoyed a pleasant local economy and controlled an important crossroads on the watershed ridge (where roads ascend from Tekoa and the Herodium in the southeast and from the Elah Valley in the southwest), but the city seems to always have sat in the shadow of Jerusalem and Hebron, its larger neighbors north and south.

Micah’s assessment, made in the mid-eighth century bc, fits the archaeological, geographical, and historical data: “But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah, though you are small among the clans of Judah” (Mic 5:2 NIV). All indications suggest that this was still the case at the time of Jesus.

The nature of a katalyma

The birth of Jesus is a Bethlehem story that fits nicely with what is known of the cultural and geographical context of the village in the first century ad. It starts with Joseph and Mary’s journey to the village to register for the census (Luke 2:4).

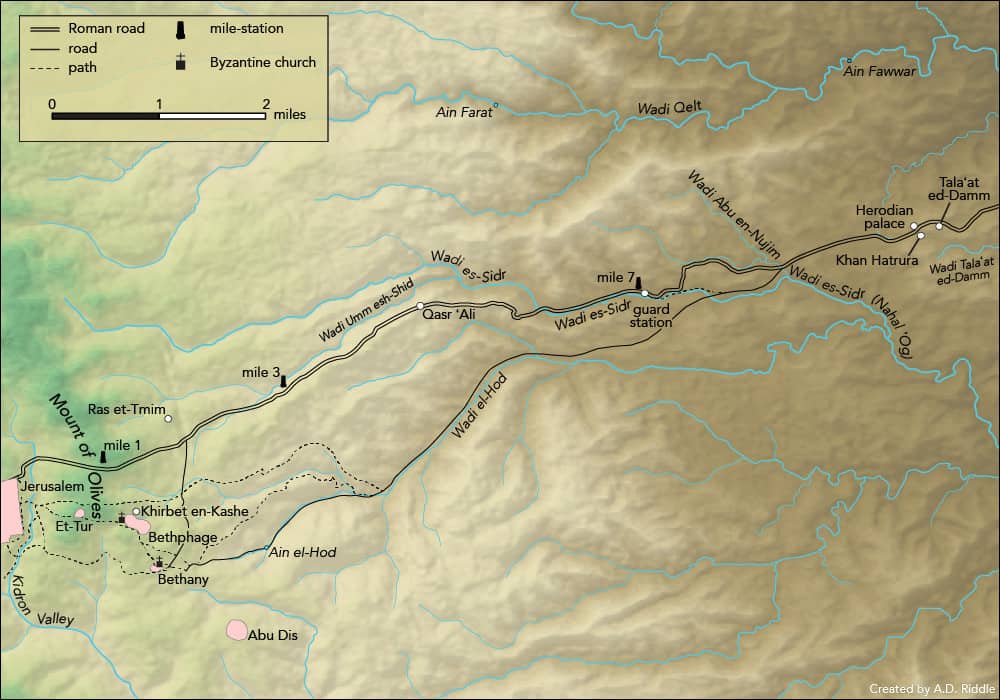

Travel in the region was a dangerous enterprise in ancient times, and finding a safe place to spend the night posed a particularly difficult challenge (see Judg 19:15). A traveler preferred to stay with extended family or, if that were not possible, where he or she could claim prior connections (e.g., with the friend of a friend).

Most houses (be they of a commoner or a king) had a guest-room or lodging place (katalyma, κατάλυμα) where a traveler could pause to eat or sleep for a period of time. This is the word that is usually, though incorrectly, translated “inn” in Luke 2:7. When in the katalyma, the traveler received the hospitality and protection of the family who lived there.

There were proper inns (pandocheion, πανδοχεῖον) at certain places along the network of roads in the Roman Empire, though only one is mentioned in the Gospels: the inn of the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:34). That story reflects travel conditions that could be found on the road between Jerusalem and Jericho, a route essentially absent of houses and hence guest-rooms. The Mishnah (m. Yebamot 16:7) also mentions an inn on the road from Jerusalem to the Dead Sea, though likely from a later period. In any case, it seems as though proper inns were not a significant part of first century ad Judea, and that travelers who were fortunate enough not to overnight in the open typically stayed in a katalyma instead.

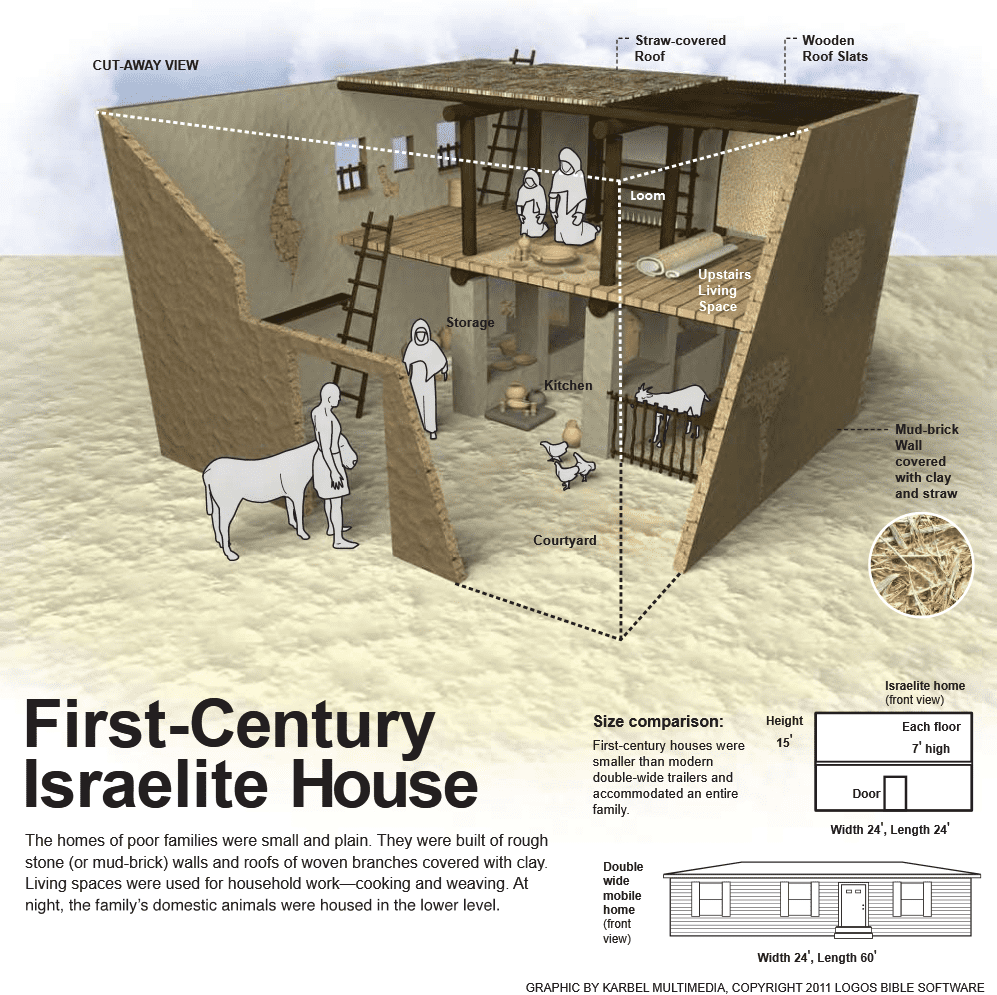

Village houses of the first century ad were composed of a number of small rooms and open courtyards with no fixed floor plan per se. Styles of housing differed regionally (Galilee vs. Judea, for instance), but the functionality of space was rather consistent. For instance, rooms that were more private in character (e.g., the place where the homeowner and his wife slept) tended to be toward the back of the housing compound, well out of view of visitors, while spaces for public activities such as wedding feasts or acts of hospitality were up front, closer to the street.

Some of the rooms and/or courtyards were reserved for the family’s animals (a donkey or two, perhaps, and the sheep and goats). Flocks and herds were brought into the household compound in times of danger or inclement weather, and their body heat slightly warmed the living spaces of its residents.

In villages built in the hill country, houses could easily have multiple stories, especially if the building was located on a slope. In this case, the room for the animals was typically in the lower story while the family lived above.

In any case, because the katalyma served guests rather than persons who were permanently attached to the household, it was likely a room close to the front of the house, near the street.

Traditional village homes throughout the Middle East today are arranged the same way, and a visitor will invariably find himself or herself hosted in a place within the household compound that is somewhat detached from rooms where the regular daily activity of the household takes place.

There was no room, we read, for Mary and Joseph in the katalyma of the house where they intended to stay in Bethlehem (Luke 2:7).

All the protocols of hospitality operative in the ancient Near East suggest that this was the home of a relative, and it was blood ties that had brought Joseph (and Mary) to Bethlehem for the census in the first place (Luke 2:4).

Why there was no room in the katalyma is a matter of speculation.

Perhaps the homeowner was already using the space for other purposes. Perhaps other guests were already in town for the census. Or perhaps this was simply not an appropriate place for someone to give birth, reading Luke 2:7 idiomatically, “there was no room there for that.” This latter suggestion is supported by birthing practices that have been documented in traditional village homes in places such as Bethlehem prior to the introduction of hospitals in modern times. At the moment of birth, the expectant mother would go to the room where animals were normally kept (the stable) to give birth, and only later was brought back up into the living spaces of the housing compound.

Because this was a time of year when shepherds were out in the fields (Luke 2:8), the stable of the house likely would have been empty or used for storage, not filled with live animals.

In the mid-second century AD the church father Justin Martyr wrote that Jesus was born in a cave (Dialogue with Trypho 78).

It is generally accepted that when Constantine first built the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem some eighty years later, he located the altar of the church over that cave. Today there are a number of interconnected caves under the church; the one that is directly beneath the altar remembers the spot of Jesus’ birth and the place of the manger in which he was laid.

Village houses throughout the hill country of Judea often were built in front of or over caves, with the cave serving as the original room of the house and eventually becoming a place for storage or for animals.

Other than through the collective weight of Church tradition, it is impossible to know if the cave under the altar of the Church of the Nativity is actually the birthplace of Jesus or not. At least the memory of Jesus having been born in a cave is consistent with the most reasonable understanding of living conditions in first century AD Judea.

In all of this, Jesus’ birth was quite unremarkable: the point is that God became a human, and the fact that he did so in a very normal birth process only heightens the intimacy of the incarnation.

***

For more insights into Scripture, pick up your copy of the Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Gospels today.