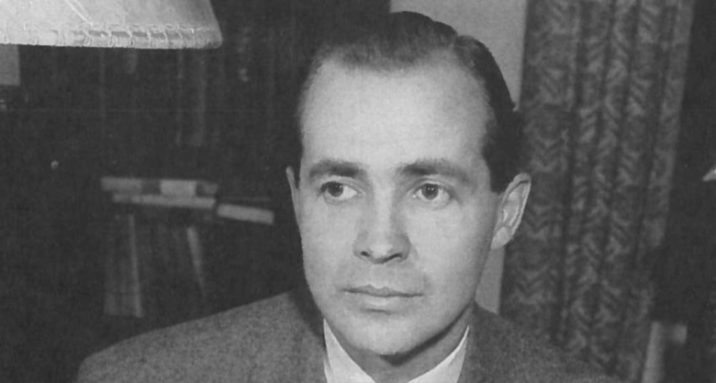

Put your ear to the ground in Ascension Presbytery in Western Pennsylvania, and it won’t be long before you hear people talking about the life and influence of Dr. John Gerstner (1914-1996). Gerstner was a longtime seminary professor and Reformed theologian in this area, and deeply affected the lives of very many people. Gerstner was Westminsterian in his doctrine and Edwardsian in his convictions. He mentored an entire generation of pastors to savor the doctrines of grace, with a zeal for revival and denominational renewal.

Gerstner died my freshman year of college at Malone University, and I was only just then becoming aware of his more-famous disciple, R.C. Sproul. As I drove the cold commute from Akron to Canton to study the Scriptures as a Bible major, I had two hopes every morning as I scraped the snow off my windshield — that my car would start in the dead of winter, and that Sproul’s radio show “Renewing Your Mind” would come in clearly in my red 1988 Ford Escort. I didn’t quite know what was happening then, but I was being pulled towards the holiness and sovereignty of God through the voice of Jonathan Edwards, speaking silently through John Gerstner, who himself was speaking vicariously through Sproul’s successful radio show.

Like many evangelicals, it was R.C. Sproul who slowly led me like a gravity beam into Reformed theology. In 1996, barely nineteen, I had no idea that I would eventually become a Presbyterian pastor myself, much less join the very presbytery that Gerstner had himself joined. In fact, in a great serendipity, the church that I now pastor, Gospel Fellowship PCA, was the very location that Gerstner was examined before Ascension Presbytery when he finally left the mainline denomination, and joined the more theologically conservative PCA.

If Sproul was the voice of the emerging Reformed renewal that would later blossom into full flower as a Renaissance of confessional theology, Gerstner was the man standing behind it all with his hands metaphorically upon Sproul’s shoulders. Sproul would many times over declare his devotion to his beloved seminary professor, as many in our neck of the woods would do as well. Gerstner gave Sproul and his cohorts a thorough education in Reformed theology, even as Gerstner channelled his own dead mentor, Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) in content and tone.

Gerstner’s influence was substantial in our area of the country, and it never lacked an Edwardsian passion and ethos. The rugged professor first taught at Pitt-Xenia, then later the same seminary as it existed after it was subsumed into the mainline church. Gerstner’s smaller United Presbyterian Church would likewise be folded into the megalith that eventually became known as the PC(USA). In that transition, Pitt-Xenia would change names to Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, and the institution itself would likewise take a hop, skip, and a jump as the progressive trajectory lurched laterally to the left.

Gerstner, though, was a veritable tour de force to evangelical pastors-in-training like Sproul, who held to the Bible’s inerrancy and infallibility. Lecturing and writing relentlessly against anything that he perceived to be a threat to Reformed and Evangelical confessionalism, Gerstner, like Edwards, defended Calvinism against the perceived dangers of his day. All the while, Gerstner preached and taught with a certain dignity and divine gravity of a man who commanded attention. Like Edwards before him, he preached and taught on the greatness of God, the necessity of conversion, and the reality of hell.

Gerstner never backed down from controversy and took on what he believed to be his opponents: liberalism, dispensationalism, and the cults. He often embroiled himself in local and denominational affairs as he did with the Kenyan and Kaseman cases. In the former, Gerstener defended a student who the mainline rejected for not being willing to ordain female pastors. In the latter, Gerstner spoke and wrote against an incoming minister who would not affirm the deity of Jesus Christ. In both cases, the mainline denomination pushed Gerstner to the right margin, even as they moved left.

Just as Edwards lost his pulpit as pastor of the Northampton Church in 1758 for his position on the Lord’s Supper, so also Gerstner lost his position as editor of the Yale Series of Edwards’ sermons for being too… Edwarsian. True enough, the managers of the authoritative Yale Editions of Edwards’ works removed Gerstner from the project because he too wholly embodied Edwards’ own thought. How can one be objective, the committee reasoned, if he actually agrees wholesale with the man he is studying? (Perhaps the committee thought that Perry Miller’s ardent atheism was more objective, since he agreed with Edwards on virtually nothing.)

Jeffrey S. McDonald’s new book, John Gerstner and the Renewal of Presbyterian and Reformed Evangelicalism in Modern America (Pickwick, 2017), does a decent job detailing the life and controversies of Gerstner, even if, according to many here in Western PA, it didn’t really capture the ethos of the man. His magnanimity, his rhetorical power, his channeling of Edwards’ passion for revival; these don’t carry over well in book form. But, in McDonald’s defense, how can an academically oriented biography be faulted for failing to capture such a three-dimensional personality? Men like Gerstner and Edwards are complex figures. They don’t come around often. They rise in influence and fall from the grace of the institutional powers-that-be. They preach with passion, and attempt to be faithful in their generation. They are misunderstood and often marginalized. They are all too clear.

In any case, Gerstner lost his position as editor of the Yale edition, and Jonathan Edwards studies as an academic enterprise lost an advocate who perhaps advocated too enthusiastically. This did not stop him from lecturing and writing about the Great Awakening revivalist. Gerstner took his show on the road, bringing lectures about Edwards the Colonial preacher to Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, to Geneva College, and to wherever else he was invited. Gerstner worked hand-in-hand with Sproul at Ligonier, and the more famous student promulgated his master’s materials. As he aged, Gerstner didn’t lose his position as a stalwart Reformed theologian so much as the institutional church closed its ears to his message. Gerstner preached his own unique versions of Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, even as the culture writ large moved towards an ever-tolerant, if cartoonish, God befitting a secular modern society.

There is a sense in which we can say that men like Gerstner, and Edwards before him, “lost” their battles with Culture. Edwards’ fear that orthodox Calvinism would one day be overrun by Enlightenment theologizing came true. Gerstner’s fear that the mainline denomination would veer towards the cliff of subjective relativism was likewise realized. But at the same time, the voices of these great men have a way of echoing off the walls and coming back again. Now that Sproul is gone too, Reformed evangelicalism will have to depend on others to preach the Gospel of free grace in Christ.

Hopefully there is another generation of young men listening to old Sproul and Gerstner tapes as they drive even now.

Dr. Matthew Everhard is the Senior Pastor of Gospel Fellowship PCA, in the Ascension Presbytery of Western Pennsylvania. He is a Jonathan Edwards scholar, and writes and lectures on the Northampton divine from time to time. He is also the author of A Theology of Joy: Jonathan Edwards and Eternal Happiness in the Holy Trinity (Fort Worth, TX: JESociety Press, 2018).