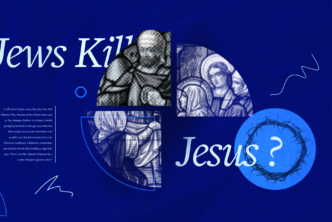

One of the most challenging areas to speak about earnestly is our treatment of the Holy Scriptures. Within the Evangelical community, words like inerrancy and infallibility have been weaponized to intimidate and silence people who are asking simple questions of the text and the Christian community for its adherence to it.

Many Christians know little about these words or their meaning, and even fewer understand how a believer and a non-believer can read the same text and yet come away with entirely different understandings of it. For this, I think it is essential that we look to one of the most formidable theologians in the church’s long history named Karl Barth.

Within Barth, there is a fresh and vibrant way in which to view revelation as well as better understand the human element within the text itself. To do this, we are going to go on a little journey together.

- In this first article, I intend to lay the groundwork for Barth’s refreshing perspective by presenting his ideas.

- The second article will look at Evangelical interactions with Karl Barth’s views of Scripture and present their opinion of his ideas.

- Finally, the last piece will look at those interactions and critique them in return, exposing some of the circular logic and irrationality behind much of their critiques.

At the end of this journey, I hope that I will have convinced you that there is a better way forward, a better way to understand the Scriptures, a way that allows God to be God, Scripture to be literature, and humanity to be human.

Karl Barth’s Doctrine of the Word of God

To understand Barth appropriately, it is important to understand the environment in which he did theology. Barth, originally, was a student and adherent to liberal theology.

As a young pastor Barth began to work his way through the book of Romans and in so doing wrote a commentary on the book. In the writing of this commentary Barth came to find that his capitulation to the enlightenment was not only unwarranted but also dangerous.

Ramm sums up Barth’s judgment of liberal theology in one sentence, “…liberal Christianity is not Christianity as historically understood and is therefore not Christianity.”1

Much of Barth’s criticism of liberal theology is their treatment of the Scriptures. For liberal theologians, Scripture was merely a human work completely fallible and incoherent in almost every way. Barth took major issue with these points as he believed that the Scriptures were in fact true.

Barth discusses his doctrine of the Word of God in a more holistic sense than just as the Scriptures. For Barth, the Word of God is expressed in three ways; as the Word of God preached, as the Word of God written, and the Word of God incarnate.2 For Barth, these modes of the Word of God all possessed two natures, divine and human.

The Word of God Preached

Barth begins with the Word of God preached, mostly due to it being the very thing that brought him out of liberalism. For him, the Word proclaimed to the church was something of foundational importance to the life of the church.

Barth before coming out of liberalism labored over the text and his preaching of it, but over time began to realize that these sermons, in accordance to the liberalisms thinking, could only be “religious discourse.”3 For Barth then, the Word proclaimed was what must be taking place when the Scriptures are preached or else the preaching is nothing more than religious discourse, which is useless to humanity.4

Preaching involved a human element and for Barth the preparation of the preacher with time spent in prayer and meditation was absolutely vital to bringing about the Word of God in preaching.

The Word of God Written

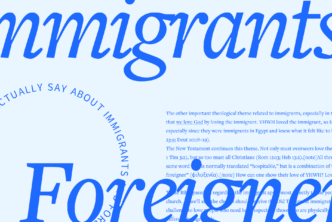

Barth also recognized the Scriptures as the Word of God or more correctly as “witness” to the Word of God. For Barth, Scripture had within it a diastasis or distance between the Word of God and biblical text. This distance was created by language, societal culture, terms of phrase, and worldviews.

In other words, when the authors of the Scriptures received the Word of God through the Holy Spirit, they took the Word of God and articulated it within their circumstances, worldview, and common philosophies of the day.

For the modern reader, this distance can and often does create issues. The Word of God must be sought out in the Scriptures as they are hidden by the particulars of humanity that reside within the text itself.5 Barth also saw Scripture as witness to the Word of God as well as “participants” in the event of revelation.6

The Word of God made Flesh

The Word of God incarnate refers to the person of Jesus who is the full revelation of the invisible God made visible. Christ is the only true, perfect revelation of God and in so being makes all other manifestations pale in comparison.

If Christ, is the perfect full revelation of God then this would mean (for Barth) that preaching, and the Scriptures cannot be the Word of God in and of themselves (ontologically). Scripture becomes as witness to the Word of God in its proclamation of Christ.7

Human and Divine Nature

For Barth, the Word of God had two natures; a divine nature and a human nature. First it would be advantageous to interact with the human nature of the Scriptures.

Ramm begins an interaction with Barth’s concept of the humanity of the Scriptures as frankly as possible in writing, “Any doctrine of Holy Scripture and its inspiration that does not come to the fullest, frankest, most honest confrontation with the full range of the humanity of Holy Scripture will certainly be written off as obscurantist.”8

Ramm’s goal in writing this is meant to call out all those who pretend to deal with the humanity of the Scriptures while also explaining away anything observable making this reality true.

For Barth, the reality was taken far greater than the breadth of evangelical theology is comfortable with. Barth, stated that the Scriptures are not inerrant or infallible and are not in fact the Word of God at all but a very human work. For Barth this does not appear to be an issue as he states in his great work, Church Dogmatics when he writes,

If God was not ashamed of the fallibility of all the human words of the Bible, of their historical and scientific inaccuracies, their theological contradictions, the uncertainty of their tradition, and, above all, their Judaism, but adopted and made use of these expressions in all their fallibility as witness, and it is mere self-will and disobedience to try to find some infallible elements in the Bible.9

It is interesting here to note that Barth states that God is not embarrassed by the fallibility of his witness. A good question to ask regarding this is how does Barth know that this does not bother God? Where in Scripture can we find such an actuality?

It appears for Barth that this fact is common sense, for if God had wanted a perfect book that was perfectly dictated in every way, he would have never included the human element in the writing of his self-revelation. Barth seems to be taking the presupposition that to be human is to err, or is he?

According to Ramm, Barth is not stating that to be human is to err ontologically, just that it is a matter of observable and empirical fact that to be human is to err.10 This then seems to be less of a presupposition as much as it is an accurate observation of human behavior.

For Barth, in order for the biblical text to truly be true, man must err. If it does not, then theologians are in reality paying lip service to the humanity of the Scriptures instead of embracing its reality.

Barth does not make this judgment as a compromise with the enlightenment and has more to do with an honest understanding of the true nature of Christ incarnate. Christ was true God and true man in every way. Christ in his humanity had the propensity for sin and was indeed tempted, as humans are tempted to sin so that he may sympathize with humanity (Heb. 4:15).

Barth also affirms however that the Scriptures are totally and completely divine. In fact, he states that the Scriptures are both normative11 and infallible.12 While Barth accepts the humanity of the Scriptures, he knows that on account of the Bible’s inspiration and it’s “becoming” in encounter that the Scriptures are true and divinely authoritative for the church. Barth sees this becoming as a reflection of the person of God. Morrison writes,

…for Barth God’s, ‘being in becoming’ reflects the fact that the living God can reveal himself, and that this is a capacity of pure grace and does not arise from necessity. God’s revelation is his Self-interpretation; in God’s revelation ‘God’s word is identical with God himself.’ Revelation is that event in which the being of God comes to word, and Revelation is, too God’s free decision in eternity to be our God, and so to bring himself to speech for us.13

In making the revelation event and Scriptures a witness to that event, Barth in affect states that Scripture is a recording of that revelation and as such, becomes the Word of God as the Holy Spirit encounters the reader in a moment in time. God is continually active in the action of bringing about revelation to his people through His Scriptures.

The Thematic Center

Lastly Barth’s entire theological construct will be misunderstood and fall apart if it is not made clear how Barth interprets and looks at text. And so, because of this, it will be the last thing discussed in this section before moving on to deal with evangelical assessments of Barth.

For Barth the Scriptures are thoroughly Christological, both in theme, and in substance. The spoken Word (preaching) and the written Word (Scripture) both reflect and bear witness to the true, perfect revelation of God the true Word of God Jesus Christ.

For Barth reading the entirety of the Bible (both the Old and New Testaments) Christologically helped him to see the Scriptures as being unified in theme. This as Ramm puts it is not Barth,

…announcing a Christological system. He is not offering a plan or a schema whereby all the different parts can be harmoniously adjusted to each other. Rather, what he suggests is more like a unifying theme, like the plot of an involved novel; the reader is not sure how all the parts of the novel fit together yet knows what the novel is all about.14

Keep Reading

Evangelical Critiques of Barth’s View of Scripture: Part 2 of 3

Assessing Barth’s Evangelical Interlocutors: Part 3 of 3

Related Resources

- Bernard Ramm, After Fundamentalism: The Future of Evangelical Theology (New York, NY: Harper & Row Publishers, 1993), 37.

- Trevor Hart, “The Word, The Words, and The Witness: Proclamation as Divine and Human Reality in the Theology of Karl Barth,” Tyndale Bulletin 46, no. 1 (1995): 85.

- Ramm, After Fundamentalism, 52.

- Ibid., 53.

- Ibid., 92-93.

- Ibid., 93.

- John Douglass Morrison, Has God Said?: Scripture, The Word of God, and the Crisis of Theological Authority (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publishers, 2006), 155.

- Ramm, After Fundamentalism, 101.

- Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, I/2, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2010), 531.

- Ramm, After Fundamentalism, 104.

- Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, III/4, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2010), 7.

- Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, III/1, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2010), 23.

- Morrison, Has God Said, 156.

- Ramm, After Fundamentalism, 128.