A review of Candida R. Moss and Joel S. Baden’s recent monograph, Reconceiving Infertility: Biblical Perspectives on Procreation and Childlessness (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Stigmatizing the Childless

Modern Western society espouses values of acceptance and tolerance of all people, regardless of religion, race, gender, personal life-choices, or disadvantages of any kind, whether physical, social, economic, political, or psychological.

Yet lived experience rarely matches this ideal, and individuals and groups regularly find themselves ostracised on the basis of just such factors. Those without children provide one example, as they do not meet society’s expectations of what a “family” should look like.

The choice not to have children is an increasingly popular one, especially for women who may wish to focus on pursuing a career; feel a child limits their freedom to live the life they desire; or simply do not feel ready to begin a family. Contrasting with those for whom childlessness is a choice are the clinically infertile, those who cannot have children even should they desire them.

Society may claim to champion freedom and support the disadvantaged, but the stigmatisation of the childless is very real.

Reconceiving Infertility

This issue forms the basis of Candida Moss and Joel Baden’s re-examination of biblical texts surrounding fertility in Reconceiving Fertility: Biblical Perspectives on Procreation and Childlessness. In a world where fertility treatments, IVF, sperm donors, and adoption appear frequently in the news and are part of our everyday vocabulary, it is shocking that those suffering from infertility are made to feel guilty and inadequate for a condition beyond their control.

In their despair, these individuals may turn to religion, hoping to find there some encouragement in their desperation. However, the Jewish and Christian traditions have firmly entrenched the need for humans to “Be fruitful and multiply” (Gen 1:28), with barrenness and childlessness being most commonly regarded as a curse, or even disobedience of a divine command.

With a firm underpinning in scholarly literature and exegesis, Moss and Baden challenge such assumptions, highlighting the diversity of biblical traditions about fertility and thus reclaiming the Bible as a source of hope and authority for all.

Introductory Issues

The introduction to this work is itself an invaluable contribution to discussions of the topic, not just within the narrow realms of biblical study. Moss and Baden deftly highlight the relationship between childlessness and the gender stereotypes that continue to dominate in modern society.

Angela Merkel and Traditional Roles

A number of issues are covered. Using Angela Merkel as a test case, the authors explain that women are berated, facing charges of unwomanliness, if they do not become mothers. Ironically, feminism, for all its virtues in liberating women from roles assigned them by patriarchy, makes it difficult for women to subsequently desire traditional roles as wives and mothers.

Notions of the blessing and divine command of fertility, manifested for example in 2014 by the Pope’s chastisement of married couples choosing to remain childless, fuel stigma, as do societal benefits for those with children, such as tax breaks. Setting (in)fertility within the context of gender and culture recognizes the issue’s pervasiveness throughout all aspects of life.

Childless or Infertile?

The introduction also fulfills the important task of defining terms. “Childlessness” refers to those without children, offering no background or explanation of how this has come to be. “Infertility,” on the other hand, is a medical condition diagnosed only after a couple that has been trying to have children consult professionals.

Moss and Baden see “infertility” fitting the modern category of a disability, as it is inherently bound up with the social and cultural context of the sufferer. In differentiating between “childlessness” and “infertility,” Moss and Baden draw attention to the complexities of this topic. This sets the reader in good stead as the study turns to biblical and post-biblical interpretations of fertility and family life.

Barrenness in the Hebrew Bible

The first set of biblical case studies tackled by Moss and Baden are the barren matriarchs of the Hebrew Bible: Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel (Genesis), the wife of Manoah (Judges) and Hannah (1 Samuel). This chapter offers three main observations.

First, in the ancient world, barrenness was catastrophic. It left the childless without social security, and prevented the continuation of a family’s line and name.

Secondly, God was responsible for childbirth because all aspects of life were religious, fundamentally relying upon divine action or inaction.

Thirdly, and most importantly, in most biblical cases of barrenness, including the five stories mentioned above, barrenness goes unexplained and is not punishment for sin. Rather, it is the natural state of woman before God intervenes to allow pregnancy to occur.

In returning to these most ancient narratives, Moss and Baden challenge assumptions that the infertile are somehow responsible for their misfortune. Already hope is offered to modern readers: the Bible may comfort and not condemn those suffering childlessness.

“Be Fruitful and Multiply”

What do such revelations mean for the command and blessing: “Be fruitful and multiply,” given several times in Genesis? In their second chapter, Moss and Baden argue that this command is rather more limited than most interpreters assume.

The command is offered to specific individuals (Adam, Noah, Abraham, and Jacob) at specific times (all prior to Israel’s emergence as a nation) and is related to national growth, rather than individual procreation.

In fact, building on Carol Meyers, the authors claim that Eve’s curse at Genesis 3:16 is the introduction of fertility, rather than painful childbirth, as procreation was unnecessary in the Garden of Eden where humans were to live forever.

The first blessing, “Be fruitful and multiply” cannot therefore envision immediate and enforced reproduction. Infertility curses are common in Ancient Near Eastern literature but the Hebrew Bible never offers barrenness as a curse in opposition to blessings of fertility.

The chapter concludes by explaining that infertility was a recognised part of life in the ancient world, and evidence for this may be seen in the Bible and the Babylonian epic of Atrahasis. The roots of Jewish and Christian tradition provide voices contravening the divine requirement for all individual human beings to procreate, a fact often neglected in religious discussions of fertility.

Mother Zion and the Eschaton

Deutero-Isaiah nationalized the image of the barren matriarch, portraying Zion as both childless and as a mother. For Moss and Baden, it is only at this point that the biblical barrenness tradition offers real hope and comfort to those suffering from infertility today. Whilst the five barren matriarchs all saw the miraculous reversal of their barrenness within their lifetimes, Mother Zion’s fecundity is transferred into the eschatological future.

Comparisons with later literature enrich this chapter, highlighting the impact of Isaiah’s transformation of the barren matriarch figure from supporting role to protagonist. Whether the eschaton features the barren being made fertile or the fertile becoming barren, postbiblical Jewish interpretation and rabbinic literature attest to the innocence of the infertile. This condition is not punishment for sin, but may even be a sign of the eschatological age within our present world.

Having laid the necessary foundations in preceding chapters, Moss and Baden here provide the true fruits of their labour, as they demonstrate the Bible’s ability to speak comfortingly to the infertile. Particularly helpful for the scholar also is the careful treatment of Zion, the most developed that I have seen in relation to the topic of barrenness.

Roman Adoption and the Gospels

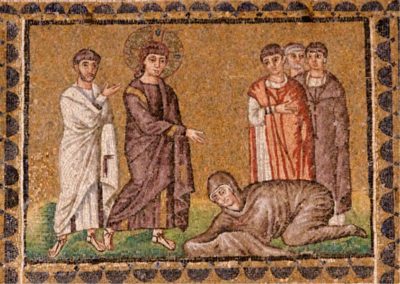

The second half of Moss and Baden’s study focuses on the New Testament and early Christian conceptions of fertility and the family. Wider cultural phenomena of the time are used to illuminate the Gospels’ portrayal of Jesus Christ’s sonship. Roman, especially imperial, adoption demonstrates that legitimate familial bonds do not have to be biological.

This is used to explain God’s proclamation of Jesus’ divine sonship at his baptism in Mark, as well as Jesus’ status as “Son of David,” emphasized in Matthew and dependent upon (non-biological) paternity through Joseph.

In John, the concept of “adopted” family is extended to Christians more generally as Jesus passes responsibility for his mother’s care over to the Beloved Disciple, asking him to treat her as his own.

Based on Luke’s presentation of Mary, mother of Jesus, Moss and Baden liberate her as a role model for all women, fertile or infertile. Mary is barren woman (akin to the Old Testament matriarchs), virgin, slave (doulos) and mother.

Moss and Baden successfully show that the ancient world provided diverse conceptions of family and of gender roles. If such alternatives were available even in the ancient world, why do we insist upon a narrow and unitary model of the family today, condemning those who do not adhere to it?

Graeco-Roman and Pauline views on the Family

Paul’s views on marriage are often summed up by the quotation: “it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion” (1 Corinthians 7:9). For Moss and Baden, Paul’s views on family life hinge as much on cultural context as on his belief in the immanence of the eschatological age, when earthly relationships would no longer matter.

Within Roman society, marriage was viewed positively and even as necessary for advancement in public roles. The Emperor Augusta, for example, in policy not dissimilar from that witnessed in modern society, rewarded men who had families, but penalized bachelors.

Equally, celibacy was seen as a virtue, the epitome of self-control. Moreover, the Greek philosopher Plato argued that the ascent of the soul could not occur with the distraction of earthly pleasures; the Stoics too encouraged continence.

This chapter undeniably provides a useful historical overview and comparison of Graeco-Roman and Pauline attitudes to marriage, chastity, and the family. However, it loses the clear focus of earlier chapters, where ancient material was continuously made relevant for people living in the modern world.

This chapter’s key arguments, namely that chastity and infertility were sometimes equated in the ancient world, and that Paul places less weight on marriage and thus on procreation (which in turn necessitates his elevation of chastity), feel strained and of little practical support to the presently childless or infertile.

Infertility and the Eschatological Age

In the final chapter, Moss and Baden again return to the eschaton, this time from a Christian perspective, and some of the study’s focus is regained. This chapter argues that infertility is a sign of the eschatological age, according to early Christians.

The story of the hemorrhaging woman as told in Mark 5 uses language of drying up, language commonly associated in Greek medical literature with barrenness. The authors thus suggest that the woman is made infertile, indicating the world to come.

Similarly, the eunuch who converts to Christianity in Acts 8 undergoes no physical transformation or “healing,” thus his infertility is unproblematic for entering the eschatological age.

According to various Church Fathers, the body will be resurrected in the end time but there will be no sexual desire and no procreation. Present barrenness hints at this perfected state and celibacy may be understood as virtuous because it imitates it.

This chapter reminds us that even if infertility is irreversible in the present, it is not punishment and there is hope for the future.

The Bottom Line

Moss and Baden’s Reconceiving Infertility is a long overdue re-examination of biblical and early Jewish and Christian interpretations of infertility and childlessness. It successfully highlights the Bible’s relevance for the modern world and allows a multiplicity of voices to be heard beyond the prevailing view of fertility as blessing.

The study covers a lot of ground well, considering biblical perspectives, early interpretations, and wider contextual influences. Its value to both academics and a wider audience is clear, as it engages in linguistic and historical critical study, whilst maintaining accessibility and lucidity in its use of ancient material to address a problem faced by many today.

Some material could be addressed more fully, for example the barren matriarch narratives in the Hebrew Bible, whose nuances and details offer endless interpretive possibilities. Understandably, however, space for such development is limited in a synoptic study such as this one.

Finally, it is worth noting that Mary Callaway’s Sing, O Barren One, cited also by Moss and Baden, is the principal study of barrenness traditions from the Hebrew Bible to rabbinic midrash. Reconceiving Infertility may be seen to complement that earlier work, as it delves into further sources, particularly Christian; further illuminates the historical backgrounds of different traditions; and demonstrates how Jewish and Christian traditions may speak positively to the childless and infertile today.