Editor’s note: The articles in our political theology series are the opinions of the authors, not those of Logos. We are publishing a breadth of voices to reflect varying perspectives within the church.

One of the distinguishing features of Jesus’s teaching was the role he assigned to love. For Jesus, love was the summation of all that the Torah taught (Matt 22:40), as well as that which marked out his disciples as belonging to the kingdom of God (Matt 5:43–48; Luke 6:27; John 13:34–35).

One interesting thing that Jesus did, unique to him as far as I can tell, was combine Israel’s profession of its monotheistic devotion to Yahweh (Deut 6:4) with the Mosaic commandment to love one’s neighbor as one’s self (Lev 19:18). When a scribe asked Jesus, “Which is the greatest commandment?” Jesus answered by splicing Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18 together:

Jesus replied: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.” This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments. (Matt 22:37–40 NIV)

Central to Jesus’s message was this double love command, calling people to exhibit authentic covenant love for God and demonstrate love for others (cf. Mark 12:29–31; Luke 10:27). According to Jesus, this was the true meaning of the Torah, not a list of rules and regulations to manufacture a micro-piety which covered every contingency in life. Rather, one was meant to experience the Torah as a spring overflowing with love: a spring filled with God’s love for us (see Deut 33:2–4; Ps 147:19–20), then flowing forth with our love for God, love for our brothers and sisters in the kingdom, and love for all people!

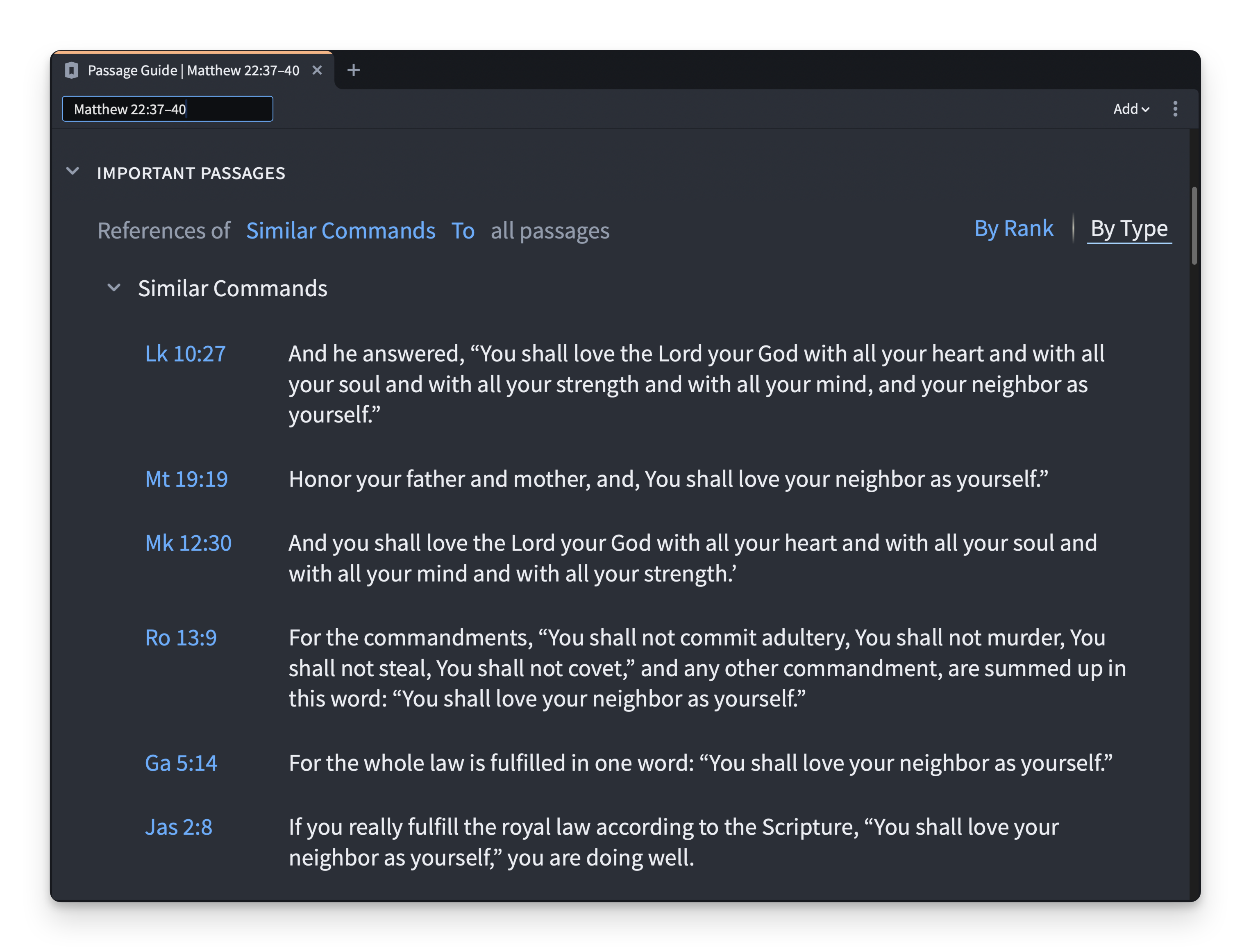

These two commands, love for God and love for others, represent the two halves of the Decalogue.1 They understandably became programmatic for Christian ethics, as ratified and rehearsed in the rest of the New Testament. For example, consider these New Testament texts:

- “My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you. Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” (John 15:12–13 NIV)

- “Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for whoever loves others has fulfilled the law. The commandments, ‘You shall not commit adultery,’ ‘You shall not murder,’ ‘You shall not steal,’ ‘You shall not covet,’ and whatever other command there may be, are summed up in this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” (Rom 13:8–9 NIV)

- “Above all, love each other deeply, because love covers over a multitude of sins.” (1 Pet 4:8 NIV)

- “If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’ you are doing right.” (Jas 2:8 NIV)

- “Dear friends, since God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us.” (1 John 4:11–12 NIV)

Moving beyond the New Testament, this love command took priority in the way the early church thought about piety and how to relate to the wider world:

- The Didache, an early second-century discipleship manual from Syria, begins with the words: “There are two ways, one of life and one of death, and there is a great difference between these two ways. Now this is the way of life: first, ‘you shall love God, who made you’; second, ‘your neighbor as yourself’; and ‘whatever you do not wish to happen to you, do not do to another.’” (Did. 1.1–2)2

- Ignatius of Antioch, on his way to his martyrdom, wrote to the Church of the Magnesians, this exhortation: “Let all, therefore, accept the same attitude as God and respect one another, and let no one regard his neighbor in merely human terms but in Jesus Christ love one another always.” (Magn. 6.2)3

- In the fifth century, the great Latin theologian Augustine made the double love command the criteria for biblical interpretation. He wrote: “Whoever, then, thinks that he understand the Holy Scriptures, or any part of them, but puts such an interpretation on them as does not tend to build up into this twofold love of God and neighbor, does not yet understand them as he ought.” (Doctr. chr. 1.36.40)4

Pastors and theologians in the early church took their cue from Jesus’s teachings and saw the double love command as the central way to think about personal ethics (Didache), public witness (Ignatius), and biblical interpretation (Augustine). This tradition was repeated with great frequency among theologians and authors throughout church history.

I would like to argue that this double love command is not simply about private faith and local church life. Nor is it reducible to ethical bare minimums, like “Don’t be an evil murderer.” Instead, I claim that the double love command ought to serve as the basis for Christian political theology. More specifically, the double love command is why we should be more inclined to support the system of government known as liberal democracy.

Using the Passage Guide’s Important Passages section, you can locate other Scriptures that repeat this command.

Love and liberalism

The word “liberalism” is heavily freighted and means different things to different people, depending on the context. Liberalism can refer to a type of theology associated with key beliefs about the authority of Scripture, the virgin conception, the atonement, the bodily resurrection of Jesus, and so forth (i.e., theological liberalism). At other times, liberalism serves as a partisan label for left-wing politics. Understood in this sense, some see liberalism as a great concept. For others, liberal functions as a byword for all that is wrong with politics and society. Liberalism is stereotyped by the “bleeding heart liberal” who cares more for criminal offenders than their victims, advocates for open borders, or promotes socialist economic policies and the like.

To be clear, none of the above is what I mean when I refer to liberalism. By liberalism, I mean neither a theological disposition hostile to traditional Christian teaching nor a partisan person whose empathy has allegedly overpowered their sense of loyalty to their own kith and kin. Rather, I am talking about the political tradition that believes human society is the happiest, most prosperous, and most fit for flourishing when citizens are seen as endowed with inalienable rights that grant them intrinsic freedoms. The liberalism of which I speak is fundamentally of a libertarian variety.

Liberal democracy, as it has been practiced in the last three or four hundred years, is an attempt to correct the fractures and failures of pre-modern Christendom. It is a rejection of the absolute power of European Christian monarchies and their colonial experiments which led to horrendous abuses of state authority.

Liberalism means that, within certain limits, society grants freedom as the norm rather than the exception, and that key freedoms can only be curtailed by necessity, with due caution, and subject to legislative review. Those freedoms include, but are not limited to, freedom of religion, conscience, speech, association, petition and protest, and commerce. Political liberalism is premised on the notion that people have the right to basic freedoms: freedom to criticize authorities, to be different, and to live one’s life without fear that a mob or monarch might coerce them into submission or eradicate them altogether.

What is more, political liberalism also has a very Protestant vibe to it! James Simpsons’ book Permanent Revolution: The Reformation and the Illiberal Roots of Liberalism argues that the British Enlightenment, far from being driven by a revolutionary strain of secular philosophy, is in fact the story of the Protestant tradition transforming and retooling itself in a more libertarian and egalitarian direction. The gains of liberalism were the unintended results of European wars of religion where a settlement was needed to protect religious citizens’ freedom from Protestant vs. Catholic socio-political hostilities and to honor the rights of smaller kingdoms not to be bullied by larger nations.

Simpson opines, however, that today those liberal gains are increasingly under threat, in part because contemporary political progressives do not appreciate the Christian roots of their own liberal tradition. Progressives fail to grasp that liberalism is not the secular antidote or alternative to theocracy-light or Christian nationalism. Much to the contrary, political progressive are riffing off tunes first played by Protestant legal theorists as they tried to imagine a more just and freer world. Political philosophers like John Locke and Hugo Grotius, the intellectual architects of modern sensibilities about tolerance, rights, and freedoms, were not trying to disavow Christianity and construct a secular alternative. Quite the reverse, they were thinking and theorizing about rights, religion, and government from within the Christian tradition. Liberalism and its progressive paternity derive not from either Marx or Mao, but more fully from the explicitly Christian writings of figures like the Spanish Jesuit Francisco de Vitoria and the American Revolution with its emphasis on “inalienable” rights for every person.

In sum, although you would never know that from listening to secular critics of Christianity, American and Western concerns for liberalism are based on Christian teaching, such as the command to love. Liberal democracy is perhaps the double love command put into practice as a political project where love as piety becomes love as public policy.

Liberal democracy is perhaps the double love command put into practice as a political project where love as piety becomes love as public policy.

Liberalism is loving because it allows us to be free to worship God according to our conscience. People must be free to love God and live their life before God according to their conscience (Rom 14). When we permit them the freedom to do so, then we are fulfilling the command to love our neighbors.

Liberalism means, within certain limits, people are allowed to think differently than us and choose their own pursuit of happiness—a proposition that is all the more attractive if you find yourself somewhere as a minority in religion, race, nationality, or regional identity. Liberalism is loving because it grants our neighbor the freedom to be our neighbor, that is, to be other than us, to be different than us, without fear of reprisal.

Remember, when Jesus was asked “Who is my neighbor?” he responded by telling his audience the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37). What makes a person a good neighbor is not their ethnicity, religion, economic status, or any other marker of cultural identity. What makes a person a good neighbor is love and mercy. If we have a liberalism based on love, then we must love our neighbors with the same love and mercy that Jesus said could be found in a Samaritan rather than in the priest or Levite. When we make love the center of our political ethics, we are required to love our neighbors and understand they are just as capable of love as we are.

Love and democracy

The Bible does not provide a manual on how to run a Christian state. In fact, God’s people in the Bible are usually beholden to their own kings, ancient Near Eastern despots, or even Roman emperors. Never in all of Scripture does anyone opine the mode of government they existed under. Christians proved capable of living under a variety of systems of government. What seems to matter most for healthy statecraft is the character and devotion of the king, not how the king came to power, his style of administration, or the distribution of authority.

Nowhere does Scripture say, “Thou shall have a democratic system of government.” But sometimes Scripture implies that good governors should covet the approval of their subjects and ask them to appoint people to represent their concerns to the ruler.

- Moses instructed the Hebrew tribes to choose leaders who were wise, discerning, and reputable (Deut 1:13–15).

- The men of Judah anointed David as king over the house of Judah (2 Sam 2:4).

- When Zadok anointed Solomon as king of Israel, it was met with public acclamation, “Long live King Solomon!” (1 Kgs 1:39).

Democracy is loving because it accords with this idea that government works best with the consent of those so governed, something the Bible and church history tacitly affirm.

In the sixth century, the deacon Agapetos wrote to the Byzantine emperor Justinian: “Count your kingdom safe when you rule with consent. An oppressed people rises up at the first opportunity, but one that is tied to its rulers by good will can be relied on to comply with government.”5 This is why the US Declaration of Independence includes the assertion that to uphold political rights of its citizens “governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

To be fair, we know that democracies are not perfect. Socrates was executed by the Athenian democracy. Britain began as a very imperial democracy with limited suffrage. The American democracy was formed principally to protect slaveholding landowners from royal interference in their efforts to expand their property holdings at the expense of the local indigenous population. Democracies can be conflictual, fractious, and partisan. Far from bringing us together, they often serve to heighten divisions! Democracy gives a voice and vote to people whose values may affront us.

In addition, democracy requires the loser to accept defeat, to accept a peaceful transfer of power, which can be hard if you think your loss was unfair, staged, or stacked against you and your political interests. This can lead to the attraction of a strong-arm leader, whether left-wing or right-wing, to abolish democratic processes and impose a naked rule of power to get things done. While democracy allows full participation in politics, it can also create the very conditions on account of which people want to and can abolish democracy for all!

Nonetheless, when you look around the world, one-party states never perform well when it comes to government services, integrity, accountability, transparency, the separation of powers, voting rights, and civil liberties. As Reinhold Niebuhr famously said, “Man’s capacity for justice makes democracy possible; but man’s inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.”6

Christians should support an inclusive democracy for two reasons. First, democracy best leads to transparent, effective, representative, and limited government. Second, government works best with the consent of the governed. In a democracy, we love our neighbors by giving them a voice and a vote equal to our own on how to create a free, just, and wholesome society.

Conclusion

The danger of liberalism is that the people may grant liberties for things that you think should be prohibited. The danger of democracy is that people who do not support your views and values may be elected to public office.

That said, liberal democracy has roots in the Christian tradition, in particular, missional Protestantism. Liberalism is a way of rejecting autocracy and ethno-religious nationalism while also promoting human rights and civil liberties. Liberalism guards our right to love and serve God according to our conscience. It is a way that we can love our neighbors by ensuring their rights to freedom and the pursuit of happiness on their own terms.

The Hebrew Congregation at Rhode Island wrote to George Washington in 1790, praising him for his virtues and the civic freedoms that they enjoyed under his administration. Washington replied to them in his famous letter:

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my Administration, and fervent wishes for my felicity. May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.7

The language that “every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid” is drawn from the messianic prophecy of Micah 4:4. It is a scriptural, not secular, statement. In fact, I’d claim that without the Hebrew prophets’ language about freedom from fear, Jesus’s double love command, the apostolic instruction to practice love as a way of life, and the political philosophy inspired by the Christian tradition found in John Locke, Francisco Suárez, Reinhold Niebuhr, and others, the liberal democratic tradition would never have come into existence.

Liberal democracy, for all its faults, is a Christian political project. It can be messy, conflictual, infuriating, aggrieving, and frustrating. But liberal democracy remains the best system of government by which fallen people can make changes based on persuasion rather than on violence, erect a bulwark against autocracy, ensure civil rights, and protect minorities from a hostile majority. Liberal democracy makes the power of love in public practice rather than the love of power in politics the rule by which nations and societies are to be governed. The role of Christians in a liberal democracy, because of its very Christian-ness, is to protect it, preserve it, promote it, and remind fellow citizens of its Christian roots.

Further reading

- Galston, William A. Practice of Liberal Pluralism. Cambridge: CUP, 2005.

- Inazu, John. Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Difference. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Niebuhr, Reinhold. The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness. New York: Scribner’s, 1944.

- Simpson, James. Permanent Revolution: The Reformation and the Illiberal Roots of Liberalism. Cambridge, UK: Belknap Press, 2019.

Religious Freedom in a Secular Age: A Christian Case for Liberty, Equality, and Secular Government

Regular price: $14.99

Jesus and the Powers: Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror and Dysfunctional Democracies

Regular price: $22.99

Related articles

- What Is the Moral of the Story of the Good Samaritan?

- When Jesus’s Command Seems Impossible: How to Love Wholly

- What Is a Protestant? Its History, Beliefs & Lasting Impact

- What Is Love? 58 Bible Verses about Love and How to Study Them

- The Kingdom of God: The Great Unfolding Drama of Salvation

- In Exodus 20:1–17, the first four of the Ten Commandments reflect how to love and honor God, while the subsequent six reflect how to relate to others.

- Michael William Holmes, The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1999), 251.

- Holmes, Apostolic Fathers, 155.

- Augustine of Hippo, On Christian Doctrine, in St. Augustine’s City of God and Christian Doctrine, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. J. F. Shaw, vol. 2, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1887), 533.

- Agapetos, Heads of Advice, 35, cited in Oliver O’Donovan and Joan Lockwood O’Donovan, A Sourcebook in Christian Political Thought: From Irenaeus to Grotius (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999), 185.

- Reinhold Niebuhr, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (New York: Scribner’s, 1944), ix.

- From George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, 18 August 1790. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05–06–02–0135.