What is the definition of logos? The Lexham Bible Dictionary defines logos (λόγος) as “a concept word in the Bible symbolic of the nature and function of Jesus Christ. It is also used to refer to the revelation of God in the world.” Logos is a noun that occurs 330 times in the Greek New Testament. Of course, the word doesn’t always—in fact, it usually doesn’t—carry symbolic meaning. Its most basic and common meaning is simply “word,” “speech,” “utterance,” or “message.”

The most famous way the Bible uses logos is in reference to Jesus as the Word, such as in John 1:1:

In the beginning was the Word (Logos), and the Word (Logos) was with God, and the Word (Logos) was God.

Logos can also be used to refer to the Bible or some portion of the Bible as the Word of God (e.g., Matt 15:6; Luke 5:1; 8:21; 11:28; John 10:35–36; Acts 6:2, 7; Heb 13:7). It often has the preeminent word or message from God in view—namely, the gospel, as in 1 Thessalonians 1:4–6:

For we know, brothers loved by God, that he has chosen you, because our gospel came to you not only in word (logos), but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction. You know what kind of men we proved to be among you for your sake.

And you became imitators of us and of the Lord, for you received the word (logos) in much affliction, with the joy of the Holy Spirit.

Interestingly, the word logos is “arguably the most debated and most discussed word in the Greek New Testament,” writes Douglas Estes in his entry on this word in the Lexham Bible Dictionary (a free resource from Lexham Press).

Learn why it’s so debated, more details about the meaning of logos, and everything else you’ve ever wondered about the word—or skip to the topics that interest you.

- An in-depth look at the meaning of logos

- Where is logos used in the Bible?

- The significance of Jesus as the Logos

- The historical background of the concept of logos

- Resources to help you study Jesus as the Logos

- The Greek background of Logos: etymology and origins

- The reception of the concept of logos in early church history

- Logos in culture

- 15 New Testament passages that use the word logos

- How to search for Old Testament verses that use logos in the Bible

An in-depth look at the meaning of logos

(This section is adapted from Douglas Estes’s entry on logos in Lexham Bible Dictionary .)

The Greek word logos simply means “word.” However, along with this most basic definition comes a host of quasi-technical and technical uses of the word logos in the Bible, as well as in ancient Greek literature. Its most famous usage is John 1:1:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

The standard rendering of logos in English is “word.” This holds true in English regardless of whether logos is used in a mundane or technical sense. Over the centuries, and in various languages, other suggestions have been made—such as the recent idea of rendering logos as “message” in English—but none have stuck with any permanency.

There are three primary uses for the word logos in the New Testament:

- Logos in its standard meaning designates a word, speech, or the act of speaking (Acts 7:22).

- Logos in its special meaning refers to the special revelation of God to people (Mark 7:13).

- Logos in its unique meaning personifies the revelation of God as Jesus the Messiah (John 1:14).

Since the writers of the New Testament used logos more than three hundred times, (mostly with the standard meaning), even this range of meaning is quite large. For example, its standard usage can mean:

- An accounting (Matt 12:36)

- A reason (Acts 10:29)

- An appearance or aural display (Col 2:23)

- A preaching (1 Tim 5:17)

- A word (1 Cor 1:5)

The wide semantic range of logos lends itself well to theological and philosophical discourse.1

Where is logos used in the Bible?

Logos in the Gospel of John

The leading use of logos in its unique sense occurs in the opening chapter of John’s Gospel. This chapter introduces the idea that Jesus is the Word: the Word that existed prior to creation, the Word that exists in connection to God, the Word that is God, and the Word that became human, cohabited with people, and possessed a glory that can only be described as the glory of God (John 1:1, 14).

As the Gospel of John never uses logos in this unique, technical manner again after the first chapter, and never explicitly says that the logos is Jesus, many have speculated that the Word-prologue predates the Gospel in the form of an earlier hymn or liturgy.2 However, there is little evidence for this, and attempts to recreate the hymn are highly speculative.3 While there is a multitude of theories for why the Gospel writer selected the logos concept-word, the clear emphasis of the opening of the Gospel and entrance of the Word into the world is cosmological, reflecting the opening of Genesis 1.4

Logos in the remainder of the New Testament

There are two other unique, personified uses of logos in the New Testament, both of which are found in the Johannine literature.

- In 1 John 1:1, Jesus is referred to as the “Word of life”; both “word” and “life” are significant to John, as this opening to the first letter is related in some way to the opening of the Gospel.

- In Revelation 19:13, the returning Messiah is called the “Word of God,” as a reference to his person and work as both the revealed and the revealer.

All of the remaining uses of logos in the New Testament are mostly standard uses, with a small number of special uses mixed in—for example, Acts 4:31, where logos refers to the gospel message:

When they had prayed, the place in which they were gathered together was shaken, and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and continued to speak the word (logos) of God with boldness.

Logos in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (LXX, or Septuagint, the translation of the Old Testament into Greek) use of logos closely matches both standard and special New Testament uses. As with the New Testament, most uses of logos in the Old Testament fit within the standard semantic range of “word” as speech, utterance, or word. The LXX does make regular use of logos to specify the “word of the Lord” (e.g., Isa 1:10, where the LXX translates דְבַר־יְהוָ֖ה, davar yahweh), relating to the special proclamation of God in the world.

When used this way, logos does not mean the literal words or speech or message of God; instead, it refers to the “dynamic, active communication” of God’s purpose and plan to his people in light of his creative activity.5 The key difference between the Testaments is that there is no personification of logos in the Old Testament indicative of the Messiah. In Proverbs 8, the Old Testament personifies Wisdom (more on this below), leading some to believe this is a precursor to the unique, technical use of logos occurring in the Johannine sections of the New Testament.

The significance of Jesus as the Logos

Much of what John says about the Logos can be found in Jewish literature about “divine Wisdom.” This means texts where Wisdom is “personified” probably circulated well before John wrote,6 so readers would have had some understanding of the idea behind Jesus as the Logos.

Hear from Ben Witherington III in his course, “The Wisdom of John,” on the role of the prologue in John’s Gospel (John 1:1), the profound truth that Jesus is the Logos who is both divine and human, and what it means that Jesus is the “Wisdom of God” personified:

This is why John uses logos to describe God’s revelation of himself. D. A. Carson writes in his commentary on John that God’s “Word” in the Old Testament “is his powerful self-expression in creation, revelation, and salvation, and the personification of that ‘Word’ makes it suitable for [him] to apply it as a title to God’s ultimate self-disclosure, the person of his own Son.”7

Jesus is Wisdom personified.

John intends for the whole of his Gospel to be read through the lens of John 1:1, writes C. K. Barrett: “The deeds and words of Jesus are the deeds and words of God; if this be not true, the book is blasphemous.”8

Resources to help you study Jesus as the Logos

The Gospel According to John (Pillar New Testament Commentary | PNTC)

Regular price: $33.99

The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction With Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text

Regular price: $27.99

The Greek background of logos: etymology and origins

According to Brian K. Gamel in his entry in Lexham Bible Dictionary on the Greek background of logos, the word acquired “special significance for ancient Greek philosophical concepts of language and the faculty of human thinking.” He says:

The word λόγος (logos) evolved from a primarily mathematical term to one identified with speech and rationality. At a basic level, logos means “to pick up, collect, count up, give account [in a bookkeeping sense]”—the act of bringing concrete items into relation with one another. Mathematicians used it to describe ratios, mathematical descriptions of two measurements in relationship to each other.9

Logos eventually came to communicate the idea of “giving an account,” in the sense of explaining a story. Having been identified with language, logos came to mean all that language involves—both the act of sharing information and the thought that produces language. By the time Latin gained prominence, the Greek term logos was translated with the term oratio, referring to speech or the way inward thoughts are expressed, and ratio, referring to inward thinking itself.10

This wide range of meanings for logos made it a difficult term to translate and comprehend. In the sixth to fourth centuries BC, Greek philosophers made efforts to limit its meaning to rationality and speech. Modern translators must consider the context in which logos appears since its meaning varies widely depending on the author and the time of writing.11

Historical background of the concept of logos

(This section on the historical background of the concept of logos is from Douglas Estes’s entry on logos in the Lexham Bible Dictionary.)

Many theories have been proposed attempting to explain why the Gospel of John introduces Jesus as the Word.

Old Testament “word”

This theory proposes that the logos in John simply referred to the Old Testament word for word (דָּבָר, davar) as it related to the revelatory activity of God (the “word of the Lord,” 2 Sam 7:4), and then personified over time from the “word of God” (revelation) to the “Word of God.”12

This theory is the closest literary parallel and thought milieu to the New Testament. As a result, it has gained a wide range of general acceptance. The lack of evidence showing such a substantial shift in meaning is this theory’s major weakness.

Old Testament “wisdom”

In the centuries before the writing of the New Testament, the Jewish concept of wisdom, or sophia (σοφία), was personified as a literary motif in several texts (e.g., Proverbs, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch), prompting arguments that Sophia is the root idea for Logos.13

Paul appears to make a weak allusion to these two ideas also (1 Cor 1:24). This theory may be supported by the presence of a divine, personified hypostasis for God in Jewish contexts. The concept of Sophia shares some similarities with “Word.” However, Sophia may simply be a literary motif. Furthermore, it is unclear why the writer of the Gospel of John wouldn’t have simply used sophia instead of logos.

Jewish-Hellenistic popular philosophy

Philo (20 BC–AD 50), a Hellenistic Jew from Alexandria, wrote many books combining Hebrew and Greek theology and philosophy; he used logos in many different ways to refer to diverse aspects of God and his activity in the world.14

This theory is supported by the fact that Philo is a near-contemporary of John. Furthermore, the use of the language has several striking similarities.

However, this theory has three major weaknesses:

- Philo never appears to personify logos in the same way John does (perhaps due to his strict monotheism).

- Philo’s philosophical system is complex and frequently at odds with the Bible’s worldview.

- Philo was not influential in his lifetime.

John’s theology

One theory for the origin of the logos concept in the Gospel of John comes through the evolution of Christological thought apparent in Johannine context: after working through the creation of the letters and the text of the Fourth Gospel, wherein the focus is repeatedly on the Christ as the revelation of God, the fourth evangelist may have written the prologue as the fruition and capstone of all of his thoughts on the person and work of Jesus.15

As this theory takes the thought process of the evangelist seriously, it is elegant and plausible. However, it does not actually answer the question regarding the origin of the concept, as the evangelist must have had some original semantic range for logos.

Greek philosophy

For Heraclitus and later Stoic philosophers, logos was a symbol of divine reason. It is possible that John borrowed this concept from the Hellenistic milieu in which he wrote.16

While few individuals support this theory today, early church fathers such as Irenaeus and Augustine indirectly favored it. This theory may be plausible, as Greek philosophy did have a pervasive influence on many Christian writers in the early church. However, there is no direct evidence that the writer of the Fourth Gospel knew or cared about Greek philosophy.

The Torah

In order to place the Gospel of John squarely in a Jewish context, this theory proposes that logos is best understood as the incarnated Torah.17

The theory is based on some parallels between “word” and “law” (νόμος, nomos) in the LXX (Ps 119:15); thus, one could translate John 1:1 as Jacobus Schoneveld did: “In the beginning was the Torah, and the Torah was toward God, and Godlike was the Torah.” This theory’s major strength is that it encourages a Jewish context for reading John. Furthermore, some parallels between “word” and “law” are possible. However, as there is very limited evidence for such a personified reading, this theory has received only limited acceptance.

No accepted consensus regarding the origin of the logos concept-word exists. This much appears probable: the writer of the Gospel of John knew Greek, and thus must have encountered, to some degree, at least a rudimentary Hellenistic philosophical understanding of the use of logos; however, being first a Jew, not a Greek, the author was more concerned about Old Testament thought patterns and contemporary Jewish language customs. Thus, it seems likely that, in the proclamation of the Gospel over time, these strains bore Christological fruit for the evangelist, culminating in the unique “Word” concept presented in John 1.

The reception of the concept of logos in early church history

The logos concept was a foundational idea for theological development from the start of the early church. Perhaps the earliest Christian document after the New Testament is 1 Clement (c. AD 95–97), in which the author inserts logos in its special usage of God’s revelation (1 Clement 13:3). First Clement may also contain the first existing unique, technical usage of logos as Jesus outside of the New Testament (if 1 Clement 27:4 is read as an allusion to Colossians 1:16; if not, it is still a very close parallel to John 1:1 and Genesis 1:1). A similar allusion to the logos as God’s revelation/Bible (New Testament) occurs in the Letter of Barnabas 6:1718 (c. AD 100) and Polycarp 7.219 (c. AD 120).

The first and clearest reference of logos to Christ comes in the letters of Ignatius, a bishop of Antioch, who was martyred c. AD 110 (To the Magnesians 8.2).20. By the middle of the second century, the logos concept began to appear in conventional (Letter to Diognetus 12.9),21 apologetic (Justin Martyr, Irenaeus) and theological (Irenaeus) uses. At the start of the third century, Origen’s22 focus on the logos as to the nature of Christ signaled the intense interest that Christian theology would put on the word in the future.

Logos in culture

The logos concept continues to influence Western culture. It is foundational to Christian belief. The Greek idea of logos (with variant connotations) was also a major influence in Heraclitus (c. 540–480 BC), Isocrates (436–338 BC), Aristotle (384–322 BC), and the Stoics, even becoming part of ancient popular culture (Philo). The concept has continued to influence Western culture since that time, partly due to the philosophical tradition of the logos that resumed post-Fourth Gospel with Neoplatonism and with various strains of Gnosticism. Propelled through the centuries in its comparison/contrast to Christian theology, the logos continued into modern philosophical discussion with diverse thinkers including Hegel (1770–1831), Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), Carl Jung (1875–1961), and Jacques Derrida (1930–2004).

Without the theology of the Gospel of John, it seems unlikely that logos would have remained popular into late-medieval or modern thought. Logos is one of the very few Greek words of the New Testament to be transliterated into English and put into everyday Christian usage.

15 New Testament passages that use the word logos

Mark 13:31

Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words (logos) will not pass away.

Luke 6:47–48

Everyone who comes to me and hears my words (logos) and does them, I will show you what he is like: he is like a man building a house, who dug deep and laid the foundation on the rock. And when a flood arose, the stream broke against that house and could not shake it, because it had been well built.

John 1:1

In the beginning was the Word (logos), and the Word (logos) was with God, and the Word (logos) was God.

John 1:14

And the Word (logos) became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.

Galatians 6:6

Let the one who is taught the word (logos) share all good things with the one who teaches.

Acts 4:4

But many of those who had heard the word (logos) believed, and the number of the men came to about five thousand.

Romans 9:9 (NASB)

For this is the word (logos) of promise: “AT THIS TIME I WILL COME, AND SARAH SHALL HAVE A SON.”

1 Corinthians 1:18

For the word (logos) of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.

Philippians 2:14–16

Do all things without grumbling or disputing, that you may be blameless and innocent, children of God without blemish in the midst of a crooked and twisted generation, among whom you shine as lights in the world, holding fast to the word (logos) of life, so that in the day of Christ I may be proud that I did not run in vain or labor in vain.

Colossians 1:24–25

Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church, of which I became a minister according to the stewardship from God that was given to me for you, to make the word (logos) of God fully known.

2 Timothy 2:15

Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word (logos) of truth.

Hebrews 4:12

For the word (logos) of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart.

James 1:18

Of his own will he brought us forth by the word (logos) of truth, that we should be a kind of firstfruits of his creatures.

1 John 1:1

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word (logos) of life . . .

Revelation 1:1–2

The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants the things that must soon take place. He made it known by sending his angel to his servant John, who bore witness to the word (logos) of God and to the testimony of Jesus Christ, even to all that he saw.

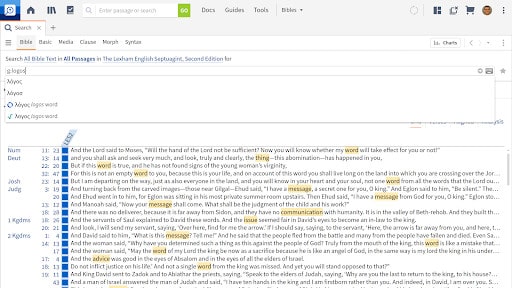

How to search for Old Testament passages that use logos in the Bible

There are more than three hundred uses of logos in the New Testament alone, but the Septuagint (LXX)—the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures—uses logos hundreds of times too. Bible software like the Logos Bible app makes it easy to find every other use of logos in the Bible.23

Here’s how. The three easy steps below show how to find verses in the Old Testament that use logos with the Logos Bible app:

- Open a new Bible Search by clicking the magnifying glass search tool icon in the top left-hand corner of the application.

- Select your preferred version of the Septuagint (the Lexham English Septuagint was revised in 2020 and is a great choice, included in Logos Starter packages and above). See how.

- In the search box, enter g:logos (this lets you search using the Greek transliteration) and choose from the options that appear (the top option is the one we’re looking for).

You’ll find over 200 results in this search, each of which offers additional insight into the biblical usage of logos.

- Peter M. Phillips, The Prologue of the Fourth Gospel: A Sequential Reading, Library of New Testament Studies (London: T&T Clark, 2006), 106.

- Rudolf Schnackenburg, The Gospel according to St John, 3 vols., Herder’s Theological Commentary on the New Testament (New York: Herder and Herder, 1968–82), 1.224–32; Joachim Jeremias, Jesus and the Message of the New Testament (Minneapolis, MI: Fortress Press, 2002), 100.

- Craig S. Keener, Gospel of John: A Commentary, 2 vols. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2003), 1:333–37.

- Douglas Estes, The Temporal Mechanics of the Fourth Gospel (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2008), 107–13.

- Stephen W. Need, “Re-Reading the Prologue: Incarnation and Creation in John 1:1–18,” Theology 106 (2003): 399.

- Keener, Gospel of John, 353.

- D. A. Carson, The Gospel According to John, Pillar New Testament Commentary (London: SPCK, 1978), 112–19.

- C. K. Barrett, The Gospel according to St John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text (London: SPCK, 1978).

- Eva Brann, The Logos of Heraclitus (Philadelphia, PA: Paul Dry, 2011), 10–11.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (London: George Bell, 1891); Stephen Ullmann, Semantics (Oxford: Blackwell, 1962), 173.

- Edward Schiappa, Protagoras and Logos: A Study in Greek Philosophy and Rhetoric, 2nd ed. (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2003), 91–92, 110.

- See Carson, Gospel According to John, 112–19.

- Martin Scott, Sophia and the Johannine Jesus, Journal for the Study of the New Testament: Supplement Series 71 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press), 1992.

- Thomas H. Tobin, “The Prologue of John and Hellenistic Jewish Speculation,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52 (1990): 252–69.

- Ed. L. Miller, “The Johannine Origins of the Johannine Logos,” Journal of Biblical Literature 112:3 (1993): 445–57.

- Norman Hook, “A Spirit Christology,” Theology 75 (1972): 227.

- David A. Reed, “How Semitic was John?: Rethinking the Hellenistic Background to John 1:1,” Anglican Theological Review 85:4 (2003): 709–26.

- So why, then, does he mention the “milk and honey”? Because the infant is first nourished with honey, and then with milk. So in a similar manner we too, being nourished by faith in the promise and by the word, will live and rule over the earth.

- Therefore let us leave behind the worthless speculation of the crowd and their false teachings, and let us return to the word delivered to us from the beginning; let us be self-controlled with respect to prayer and persevere in fasting, earnestly asking the all-seeing God “to lead us not into temptation,” because, as the Lord said, “the spirit is indeed willing, but the flesh is weak.”

- “The most godly prophets lived in accordance with Christ Jesus. This is why they were persecuted, being inspired as they were by his grace in order that those who are disobedient.”

- “Furthermore, salvation is made known, and apostles are instructed, and the Passover of the Lord goes forward, and the congregations are gathered together, and all things are arranged in order, and the Word rejoices as he teaches the saints, the Word through whom the Father is glorified. To him be glory forever. Amen.”

- Origen (Ὠριγένης, Ōrigenēs). Also known as Origen of Alexandria. A prolific and influential church father who lived c. AD 185–254. Known for his allegorical approach to interpreting Scripture.

- Though the Old Testament was written in Hebrew, seventy-two Jewish scholars translated it into Greek in the third century BC. Therefore, we can learn a lot about logos by examining this work.