As a child, I loved the Choose Your Own Adventure book series. These books allowed me to shape the story to my desires. No other book allowed that. If I did not like an outcome, I simply “rewound” my decision and chose another. The book provided the options; I determined the outcome. I fear we often wield our Hebrew and Greek lexicons as though they were like the Choose Your Own Adventure series: We open the lexicon to a word’s entry, choose from among the options on that page, and insert our choice into our translation and interpretation. But when we choose based on our desires and not the rules of the language, we make lexical mistakes and may end up with an inaccurate reading.

With access to resources comes responsibilities—responsibilities grounded in how languages work. Omitting these can lead to teachings that sound good and get passed down from one person to another, but do not observe the rules of translation.

Lexical mistakes

Responsibly wielding lexical resources requires understanding how languages work. For lexical issues, this means understanding the difference between glosses and definitions, as well as understanding the limitations of lexicons and glosses.

1. Glosses are not definitions

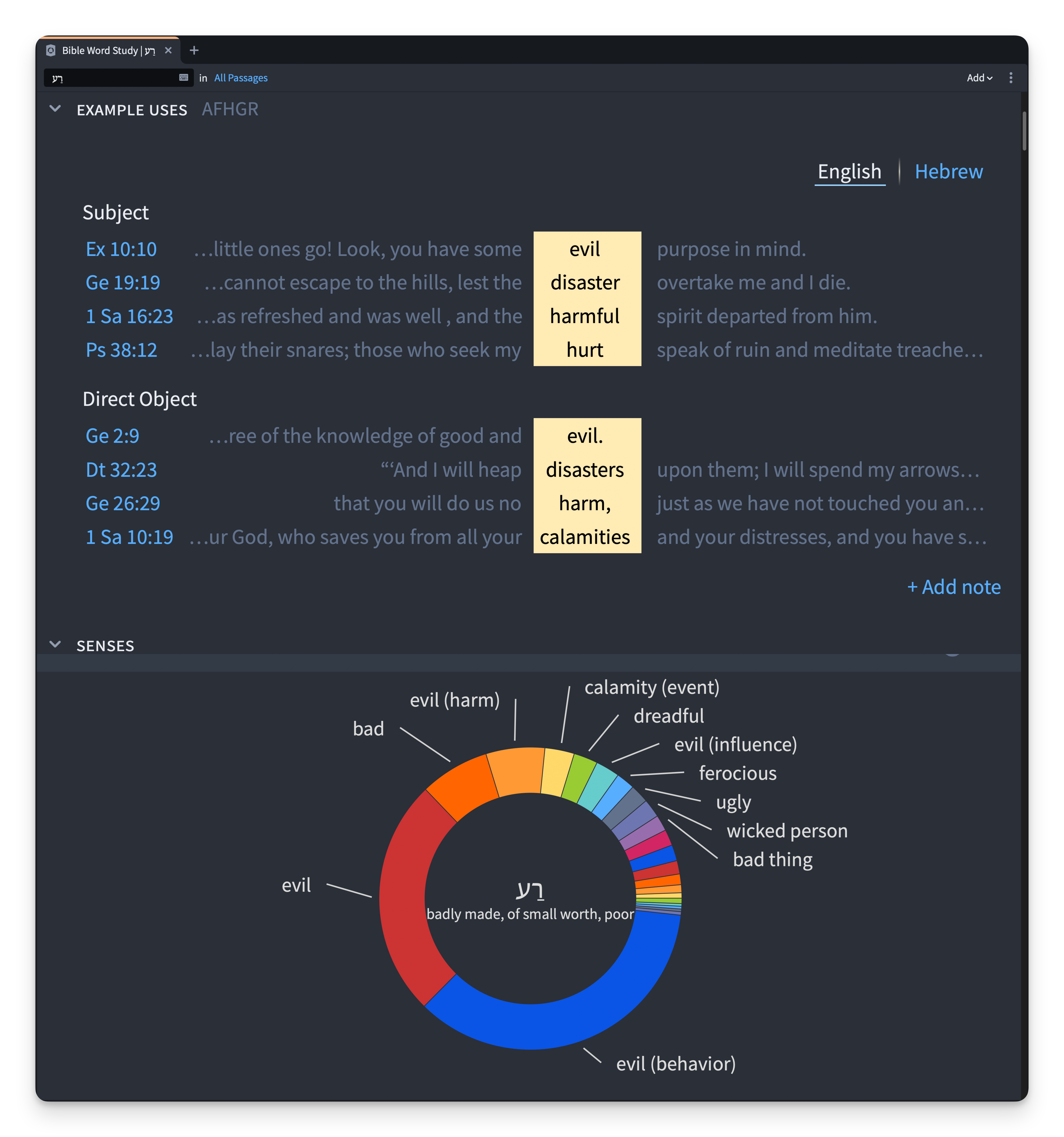

Typically when learning Hebrew and Greek you learn glosses—not definitions. A “gloss” is a fancy way of saying, This is an English word that can sometimes be used in a translation when you see this Hebrew or Greek word. For example, if you see the Hebrew word רַע (ra’) and think “evil,” you’ve just thought of a gloss—not a definition. “Evil” is not the definition of רַע, but it is a gloss for it.

Lexicons are repositories for these glosses. Sometimes lexicons provide additional explanations with the glosses, but not always.

In languages, words in isolation communicate a general broad concept (a semantic range); some words have more than one.1

But when that word is placed in a context—voila!—that broad concept suddenly has been narrowed down by the context into a specific meaning that can be translated with a gloss.

Use Logos’s Bible Word Study to explore the different senses of רַע (ra’).

Returning to our example, the semantic range of רַע is simply “unpleasant” or “bad.” When used in some contexts, the “unpleasant” thing is a moral behavior that English would call “evil.” Thus a contextual gloss for רַע can be “evil.” But in other contexts, רַע describes non-evil things such as “troubling” news (Exod 33:4), “unhealthy” cows (Gen 41:20), and a “sullen” countenance (Gen 40:7). Defining רַע as “evil” can even create an unnecessary theological dilemma in verses where God does רַע (Isa 45:7). God does not do evil, but he does judge and discipline, which is unpleasant for the people.

In other words, context must determine the appropriate gloss.

2. Glosses are not interchangeable

Since glosses must be chosen based on context, glosses are not interchangeable.

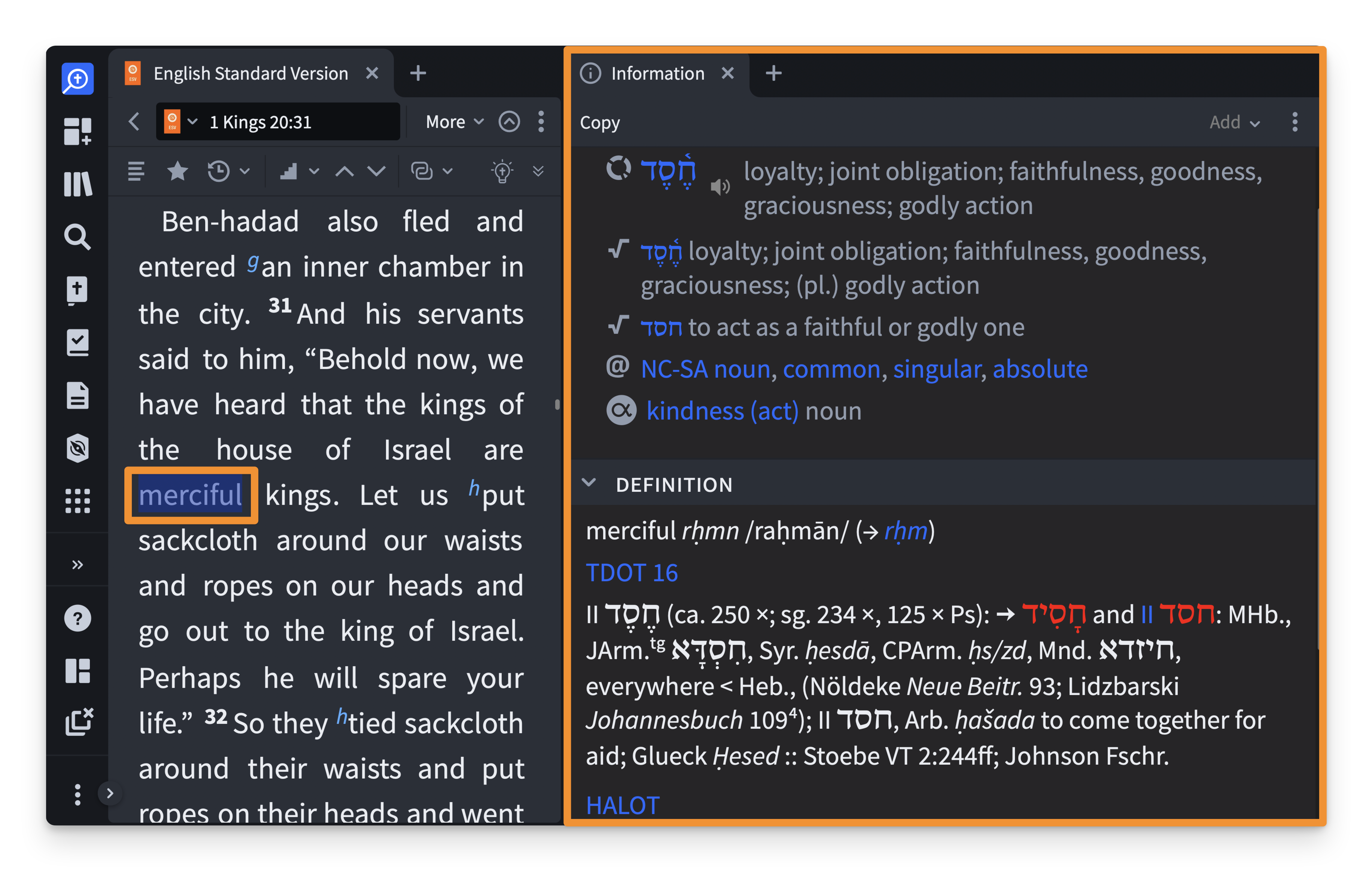

Say I’m reading 1 Kings 20:31 where Ben-Hadad is trapped by Ahab. His advisors recommend wearing sackcloth and begging for mercy because they had heard the Israelite kings were “kings of mercy” (20:31). Perhaps I’m confused about this phrase because the Northern Kingdom was not exactly a great kingdom, so why would the kings be known as merciful? I look up the Hebrew word in an effort to find an answer to my question.

Easily pull up lexical information straight from your Bible using Logos’s powerful Information tool.

The word “mercy” is the infamous חֶסֶד (ḥesed), which I look up in Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (BDB). As I skim the entry, my eyes fall upon entry I.4 that lists “lovely appearance.”2

My verse isn’t listed in that entry, but I also know that lexicons don’t always mention every instance of a word. So, I theorize that maybe what is actually happening here is that the advisors are noting that the Israelite kings were known for being lovely in appearance. So if they wear sackcloth to visually lower themselves in contrast to the “lovely” appearance of Ahab, Ahab might not feel threatened by them, and thus allow them to live. This interpretation relies on a gloss in the lexicon and it resolves my confusion with the Israelite kings being known as merciful.

I hope this example sounds ludicrous. The lesson here is that glosses are not interchangeable. In this example, I found a gloss I could use to solve my dilemma, but in doing so I chose a gloss that fit my desire, not the context. There is nothing in Ahab’s stories to suggest he was “lovely in appearance,” or that any of the kings were. Further, I failed to notice that the “lovely appearance” entry specifies flowers, not humans. I failed to notice that the lexicon actually classifies my verse under the “kindness” to “lowly, needy, and miserable” people. This fits the context, where Ben-Hadad, through sackcloth, is representing himself as lowly, and thus in need of kindness.3

The additional note that BDB provides with the contextual gloss for my verse clarifies the type of kindness, but it does not solve my dilemma about the reputation of the Israelite kings. I can’t solve that dilemma by choosing a different gloss.

A key part of avoiding lexical mistakes requires understanding the limitations of a lexicon’s usefulness.

3. Lexicons do not answer all questions

As the previous example shows, a question that leads me to a lexicon cannot always be answered by the lexicon. I must ask my question elsewhere. Wielding a lexicon will not always answer the questions you want answered.

But sometimes it does.

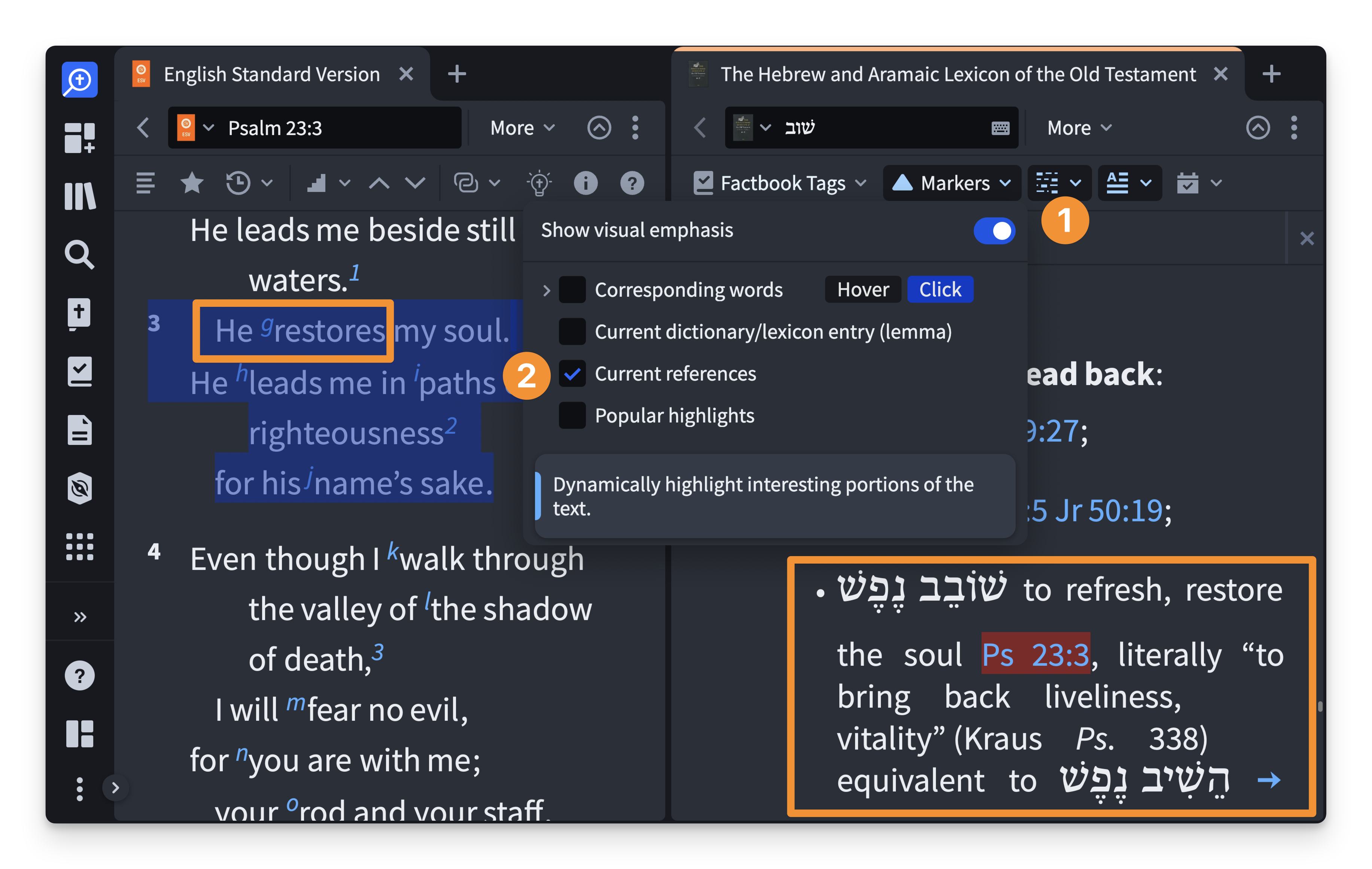

Perhaps I’m studying Psalm 23:3, and I am struck by the statement that God “restores my soul” (NASB). There are several possible ways I could understand that theologically. So I look up the Hebrew verb (שׁוב) in The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT), careful to look under the section on the corresponding verbal stem. And I see Psalm 23:3 listed with the specific gloss of “to refresh, restore the soul,” which is a subcategory under the broader contextual category “bring back, lead back.”4

In Logos, you can customize your lexicon’s formatting settings so you can find what you need in a breeze.

With this information and the context of the psalm, I am able to deepen my understanding of the psalmist’s declaration. God brings back or restores the psalmist’s life.5 Reading this affirms the translation of “restore” while also helping me ponder further the precise type of restoration.

Lexicons can help hone our understanding of why certain English translations were chosen. This can be especially helpful when an English gloss cannot fully communicate what the Hebrew word does.

4. Glosses are limited by English

When English has no perfect word or phrase for glossing a Hebrew word, the lexicons still give us English glosses—glosses that are as close as we can get in our language.

Let’s take the infamous חֶסֶד (ḥesed) again. In Micah 6:8, חֶסֶד describes what God requires of his people: “to do justice and to love חֶסֶד and to walk humbly with your God.” Many translations use “to love kindness” here (e.g., NASB, ESV, NRSV). “Kindness” comes close to the Hebrew meaning, but “kindness” is a description of a person’s disposition. חֶסֶד is that, but is also more than that.

BDB’s category for this verse provides the gloss “kindness,” but also provides an additional note saying that it is “kindness (especially as extended to the lowly, needy and miserable), mercy.”6 This additional note helps a little, but a newer resource can provide better information.

The newer HALOT glosses חֶסֶד between people as “joint obligation” and further notes that it occurs “between relatives, friends, hosts, and guest, master, and servant; closeness, solidarity, loyalty.”7 And it also allows for a gloss of “faithfulness” in these contexts.

This information changes how we understand the “kindness” of Micah 6:8. חֶסֶד is more than a disposition; it also includes the ideas of obligation and faithfulness. Read in context, God is calling them back to faithfulness to the covenant where he teaches them what justice is, their obligations to each other, and how to walk humbly with God.

Using lexicons in a manner that observes the rule of language means understanding that translation requires difficult choices, even more so when there is no perfect gloss. But there are good glosses. This is another key to avoiding lexical mistakes.

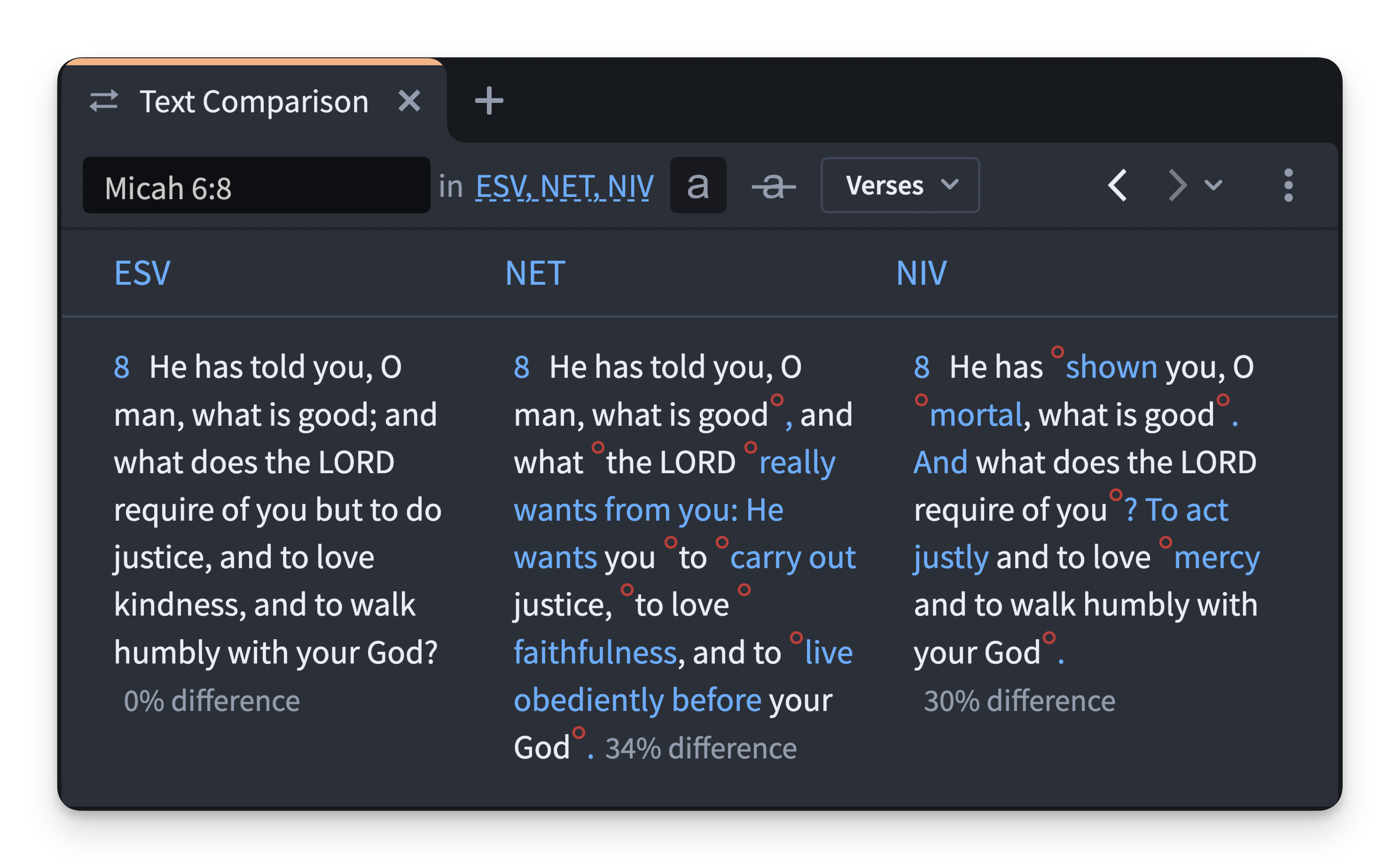

Use Logos’s Text Comparison tool to easily compare texts, like different Bible translations.

Comparing translations can help surface these issues. While most translations use “kindness” in this verse, the NET uses “be faithful.” Both glosses together provide a clearer picture of the underlying word’s meaning.

Consulting a lexicon can clarify the issue further.

Lexical resources

Responsibly wielding lexical resources also requires choosing them intentionally and thoughtfully, as well as investing in learning how to use them well.

1. Choosing resources

Wielding lexical resources responsibly begins when you choose your lexicon. When doing so, consider the age, publisher, and the author.

Age

While the biblical languages do not change, our understanding of them is constantly growing because of new linguistic research.

As a general rule, I recommend the average user of biblical lexicons should only use those published after 1990. The standard Hebrew academic lexicon is HALOT, though the Dictionary of Classical Hebrew would be the standard if it were not for the price.

Older resources, such as BDB, are easily available because they are in the public domain; but public domain language resources are outdated. In the century since BDB’s publication, we have learned that some information in BDB is not accurate. Wielding older resources requires a higher level of responsibility that many users have not been equipped for. It is better to wield English resources well than to wield Greek or Hebrew resources poorly.

Publisher

Not all resources are reliable resources. One way to ensure your resource is reliable is to consider the publisher. Reputable academic publishers will only publish language resources from well-trained scholars. This includes publishers such as Lexham, Zondervan Academic, Baker Academic, InterVarsity Press Academic, Kregel, Eerdmans, and Brill. If a resource is not published by such a publisher, you will want to carefully research the author(s).

Author

Not all authors are equipped to handle Hebrew and Greek well. There are many faithful teachers who interact with the languages. But if they are not well-trained in the languages or do not cite recent reliable sources, I would recommend holding their statements about the language loosely until you can cross-check what they said with a reliable resource. A person well-trained in the languages will typically have a relevant doctorate and they will interact fairly with recent research and resources in the field.

2. Using resources

Wielding the resources and responsibilities well might require strengthening your language skills. For an overview on how the biblical languages work I recommend Lexham’s Linguistics & Biblical Exegesis. And if you want further explanation, Zondervan’s Advances in the Study of Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic and Advances in the Study of Greek provide a more in-depth introduction to features of the languages, including chapters on lexical issues and resources.

Wielding resources well also requires training in using those resources. If you use a Bible program such as Logos, invest in increasing your skills with the software. Set aside time to read tutorials, watch training videos, and explore and test your skills. Learn to wield the software well while also evaluating which resources within it are ones you are equipped to use responsibly.

For some, wielding the languages well may require taking or auditing a class. It may involve intentionally setting aside time and money to invest in one of the many training programs crafted by scholars who exist outside the standard academic structure.

Finally, wielding the resources well requires knowing when to reconsider your conclusion. If your use of the resources leads you to a conclusion that cannot be supported by a major English translation, this signals a need to reevaluate. If scholars from the major translation committees do not agree with your conclusion, set that conclusion outside of your preaching and teaching until you can verify it by well-trained scholars.

5 encouragements for preachers and teachers

I love seeing preachers and teachers adeptly use biblical languages and avoid lexical mistakes. It is a beautiful thing. So allow me to encourage you to remember five important things about the languages and your ministry.

1. Spiritual formation is not a result of using Hebrew and Greek

Spiritual formation comes through our relationship with God and the work of the Holy Spirit within us and through the church. God can use Hebrew and Greek as a means to encourage spiritual formation, but neither you nor your people need the languages to have a healthy growing relationship with God.

2. Don’t add responsibilities beyond those God has given you

Sometimes preachers feel internal or external pressure to take on additional responsibilities, including pressure to use Hebrew and Greek in sermons. If that is true for you, please remember that God’s call is not subject to that internal or external pressure. If things have been added to your calling, those very things (yes, even the biblical languages) can hinder your faithfulness to what God has called you to. Do not obligate yourself to do something that God has not called you to do.

3. Don’t fear the languages

Sometimes a felt pressure to interact with the languages is a part of God’s calling. He may be calling you to become equipped to wield the languages responsibly. If he is, then the languages are now a matter of faithfulness in your walk. So walk in faithfulness.

4. Don’t distrust what you have

Do not fear relying on the tools God has equipped you to use. You can trust the translations while also acknowledging that they are translations. The Hebrew and Greek do not hide secret spiritual meanings left out of the translations. They are simply languages. Interacting well with them can help clarify our understanding in some areas, but there are no secrets. The God of the Hebrew and Greek texts is the same God of the English translations.

5. Don’t undermine trust in translations

And finally, in some contexts, the use of biblical languages can cause real harm. Audiences that lack discipleship on Bible translations, or are ignorant about how we got the Bible, will likely conclude that they cannot trust their English Bibles after being taught about the “real” or “actual” meaning of a Hebrew or Greek word. In such contexts, using Hebrew or Greek in your teachings requires ensuring, first, that your audience has a solid foundation of trust in their translations and then, second, that you do not undermine that trust. When you use Hebrew and Greek, make sure your people leave trusting their English translations.

JoAnna Hoyt’s recommended lexical resources

Advances in the Study of Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic: New Insights for Reading the Old Testament

Regular price: $38.99

Advances in the Study of Greek: New Insights for Reading the New Testament

Regular price: $34.99

Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament | HALOT (5 vols.)

Regular price: $159.99

Related articles

- Top Preaching Tools & Resources That Belong in a Pastor’s Library

- Was the New Testament Written in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek?

- How to Use Greek Lexicons

- There are several competing theories on how lexical meaning is created. For an overview of the theories, see Michael Aubrey, “Linguistic Issues in Biblical Greek,” in Linguistics & Biblical Exegesis, ed. Douglas Mangum and Josh Westbury, Lexham Methods Series 2 (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016), 174–83.

- Francis Brown et al., Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 338–39.

- BDB, 338.

- Ludwig Koehler et al., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994–2000), 1431.

- The word often translated “soul” here (נֶפֶשׁ) refers, not to the spiritual soul (as opposed to the body and spirit), but to the broader unseen parts of a person required for them (and their body) to be alive. See CEB translations.

- BDB, 338.

- HALOT, 336–37.