How many times have you heard this in a sermon?

How many times have you preached this in a sermon?

Faith in Greek is pistis, which means fidelity or trust. In Hebrew, the word usually translated as faith is emunah, which means steadfastness or fidelity.

Or:

The Greek word here, ploion, can be translated “ship” or, perhaps more accurately, “boat.”

I’d like to make a case that these kinds of comments are unnecessary at best, counterproductive at worst. I’m here to urge you to remember not to say “the-Greek-word-here-is” in your next sermon. And the next one.

Because I am a writer who refuses to use hackneyed rhetorical strategies, here are three breezily titled reasons for refusing to mention Greek in your next sermon or Bible lesson. Then, begrudgingly, a few reasons why you might want to do so.

Remember before you read, pastors: faithful are the wounds of a friend!

1. Don’t mention Greek in your sermon because it’s frequently redundant.

I’d say 80 percent of the mentions of Greek I hear in Bible teaching are banal observations. In my position as an editor for a Bible study blog, Word by Word, I have articles submitted to me all the time which do the same thing: leave me with no choice but to press my delete key.

I received an article a few years ago that argued that the Greek word for believe, πιστεύω (pisteuo), has a deeper meaning than the English one. So said the writer (the rest of whose piece was just fine!), the Greek word was richer and more precise than the English word “trust.” It meant “to consider something to be true and therefore worthy of one’s trust” (BDAG).

But there are several problems with this utterly standard line of argument. The main one is that this line often just doesn’t bear out when you look up the relevant English word. The contemporary English dictionary I use most often defines trust as “firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of someone or something” (NOAD). If anything, that sounds richer and stronger than the Greek word—it has the word “firm” in it.

But, of course, it isn’t richer or stronger. Believing and disbelieving are things all humans do. The direct objects of the verb “believe” in the New Testament are most frequently Christian objects, because the NT talks about believing Christ (John 3:16) and God (Jas 2:23) and the truth (2 Thess 2:12) far more than it talks about believing a mere human’s words (Luke 24:11). It is also true that “believed,” by itself with no object, comes to be used in the NT as a shorthand for “believed the gospel.” The context of the NT, in other words, fills in the missing direct object of “believe.”

And the hand of the Lord was with them, and a great number who believed turned to the Lord. (Acts 11:21 ESV)

And “believers” comes to be a word for the early Christians, without having to specify “believers in the gospel”:

Also many of those who were now believers came, confessing and divulging their practices. (Acts 19:18 ESV)

But none of this means that the Greek word pisteuo somehow means Christian belief, or belief in the gospel, or belief in God. It takes specific contexts for the word to communicate that particular (“pragmatic,” linguists call it) meaning. English is precisely the same way, or the two translations above would not work. Nobody would say that “believe” in English is a specifically Christian word. But nonetheless, people make perfect sense of Acts 11:21 and 19:18—“believed” and “believers”—without the object of belief needing to be specifically named.

So—if you point out that the Greek word for “believe” means [fill in any Greek lexicon’s definition here], you’ll only be saying, “‘Believe’ in Greek means exactly the same thing that the English word in the translation in your lap means.” You’ll be wasting 8.4 seconds of your sermon or Bible lesson on a distracting and counterproductive tautology. What could be the point of telling people who read the Bible in English something they already know, that “believe” means “believe”? People love to speculate here: maybe the preacher just likes to show off? I won’t say that. I’ll leave that between the preacher and his God.

Define the word, sure. Even use a definition from a Greek-English lexicon. But don’t tell Christ’s sheep you have access to a hidden and deeper meaning when you simply don’t. They already know that “believe” means “believe.” Don’t cock your head sagely and point it out to them again.

2. Don’t mention Greek in your sermons because there’s a good chance you’re just wrong.

About 20 percent of the time I hear mentions of Greek or Hebrew in sermons—I’m sorry to say—the preachers doing so are simply wrong somehow in their assertions. A few years back, I heard a preacher make particular mention of the fact that a given Greek word occurs only twice in the New Testament—as if that fact should lend its use more significance somehow? I wasn’t sure. Maybe he thought this was some nifty biblical–lexical trivia, or he thought he needed to justify his check of a particular cross reference (which could have been okay; he just didn’t say this).

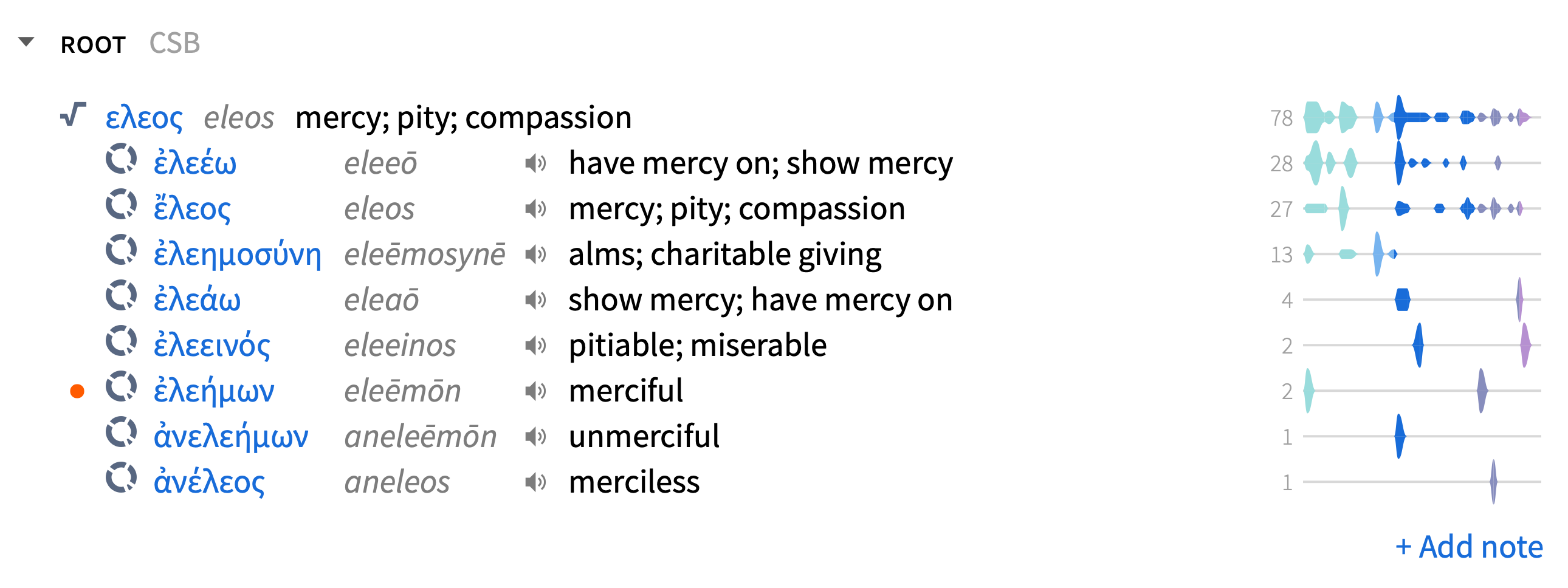

But what he said about the Greek word under discussion just wasn’t true. Yes, that particular form of the root occurred only twice. But the word was ἐλεεινός (eleeinos), and anyone who knows basic NT Greek vocabulary will see immediately that the word stems from the ελεος (eleos) root, commonly translated “mercy.” And that root shows up seventy-eight times in the NT and eighteen in the LXX.

Claiming that the word is uncommon is both meaningless in this case (it added nothing to his argument) and misleading (it’s a common root).

These are modest examples. I’ve seen preachers and Bible teachers go much further than this down the path of linguistic silliness. I’m keepin’ it vague rather than real, because I don’t want to embarrass anyone, but if preachers and Bible teachers took their too-creative linguistic energies and applied them to producing better illustrations or transitions or introductions or something, they’d hit homiletical home runs.

In fact, the preacher who made the minor, erroneous aside about ἐλεεινός (eleeinos) did so in an otherwise excellent sermon on 1 Corinthians 15. It was an unforced error—forced, I suppose, only by a set of social expectations among certain tribes of Christians that real preaching will genuflect to “the-Greek-word-here-is” in every serious message.

I’ll stop here with examples. D. A. Carson has written the classic text on the kinds of linguistic errors well-meaning preachers commit. Consider this your semi-annual PSA: please Read Exegetical Fallacies.

3. Don’t mention Greek in your sermon because it doesn’t help people read their Bibles better.

Good Bible teaching, before it is anything else, is first good Bible reading. Good Bible teaching therefore models good Bible reading. It teaches listeners implicitly, and often explicitly, how to read God’s Word on their own. I think most mentions of Hebrew and Greek do not help most Christians read their Bibles better.

May I talk for a moment about lay Bible reading?

I don’t deny that traditions outside of my own evangelical Protestantism have their strengths; I don’t deny that my own evangelical Protestantism has massive weaknesses and troubles. One of these is what Christian Smith has called “pervasive interpretive pluralism.” I acknowledge this. And I account for it: we are all fallen and finite Bible interpreters; and in these last days, even after God has spoken to us by his Son, there are plenty of self-described “evangelicals” who will not endure sound doctrine (2 Tim 4:3).

I just figure that the group that emphasizes personal Bible reading and study at least has a chance to ameliorate their weaknesses and repent of their troubles—to be reformed by the Word.

So I want my pastor to preach the Bible using reading methods that are basically replicable by my twelve-year-old. And I’ve seen this work—in myself. I should get an ironic nineties throwback hipster T-shirt that says, “Hookt on Xpository Preaching Werkt 4 Me.”

Long before I had a call to ministry and became an inveterate theological scribbler, I was a teenage graphic design major thrilled to hear careful scriptural exposition through the book of Ephesians. That same preacher said more than once that expository preaching is “caught as much as taught.” And I caught it: I read the Bible with more skill, knowledge, and confidence (and, I hope, also humility) because I was hearing careful preaching.

I do think that hearers need to be reminded that they are reading the Bible in translation. I of all people know the damage that accrues when people start to treat the translation in their hands as itself perfect and inspired. But this can be done without explicitly mentioning a Hebrew or Greek word. It can be done in a replicable way. You can say, “The Greek word that is translated ‘exult’ here (Rom 5:11 NASB) is also used repeatedly in the NT to mean something more like ‘boast.’”

Exceptions to the general rule

And that brings me to two exceptions to the general rule I’m trying to defend in this piece. These are instances when it is useful to make digressions into lexical particularities from the biblical languages:

1. When a literary device needs to be clarified.

There are, occasionally, times when a literary device in the Hebrew or Greek, one that doesn’t carry well into English, is worth mentioning in a sermon. A literary device is the kind of thing that careful lay Bible readers will encounter in the footnotes in their study Bibles, and even in non-technical commentaries. So equipping them to expect and process such things isn’t so bad.

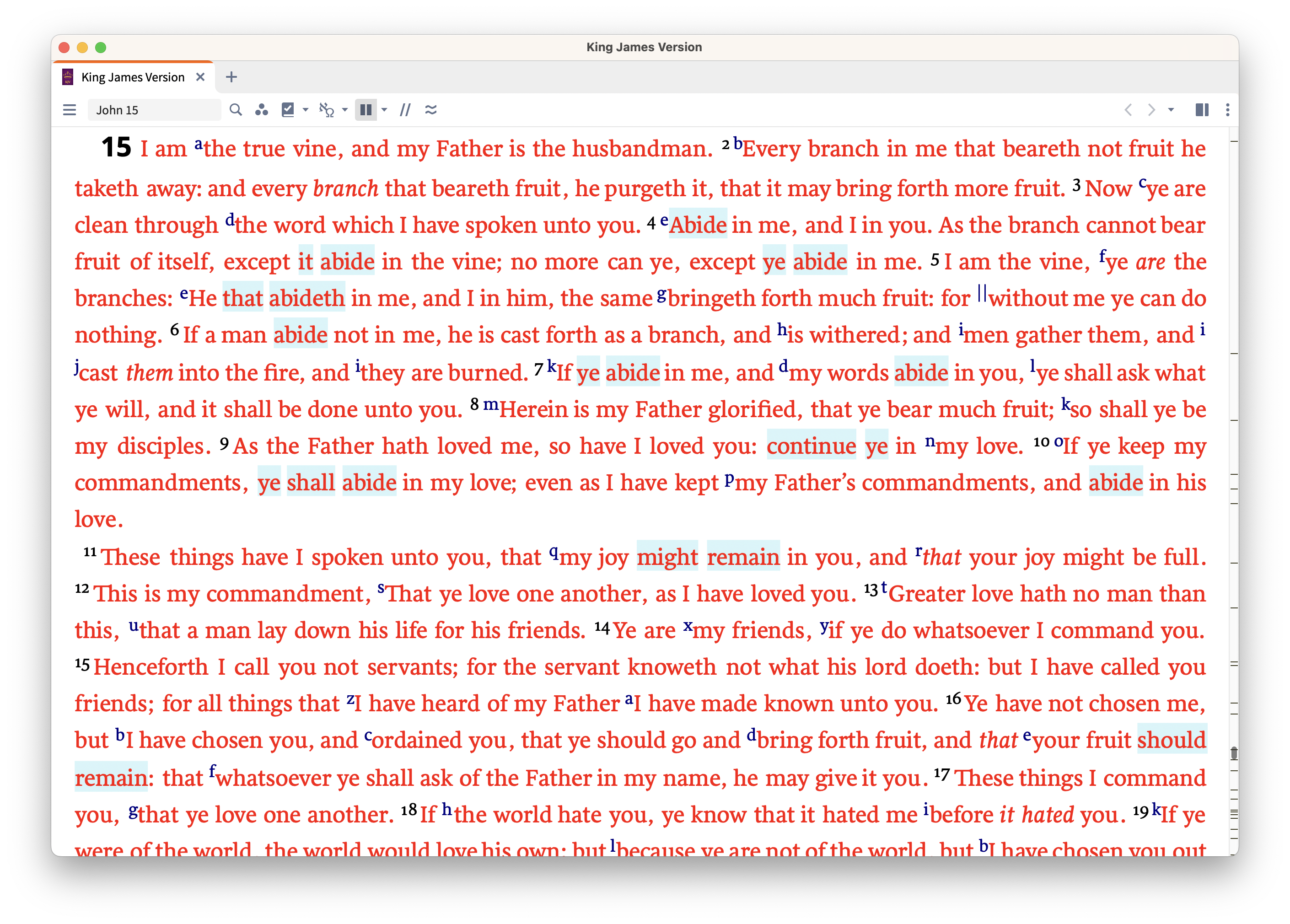

For example, the KJV translators rendered every instance of the μένω (meno) root in John 15 with the same English word, “abide”—except for three of the references. Can you spot them in the image below?

(I have “corresponding words” turned on in my visual filters in Logos; I found all these by clicking on just one of them. A nice feature I use regularly!)

I could imagine a preacher wanting to make clear that Jesus is, in the second paragraph (verses 11 and following) picking up on the theme of the first. You could preach, “Jesus spoke these things ‘that his joy might remain in’ his disciples; and that word ‘remain’ is, in Greek, the same as the word ‘abide’ in verses 1–10.” I can see some value in doing this.

But read your audience: What if for everyone in your church who cements the contextual connection in his or her mind because you mentioned Greek, there will be nine lepers who will not come and thank you after the sermon because they just got confused?

And, for what it’s worth, pointing out what’s going on in the Greek here runs somewhat counter to the advice of the KJV translators themselves—who said in their preface quite clearly that they refused to be “tied … to a uniformity of phrasing.” They thought that this kind of insistence on consistency “savour[ed] more of curiosity than wisdom.”1

What they said about translation I say about preaching. If you can’t demonstrate a given point through appeal to the (English) translations in your hearers’ laps, you probably don’t want to appeal to the Greek. But I’ve opened the door just a crack for you.

2. When a Greek or Hebrew word has become an English one.

Another circumstance in which I might willingly name a Hebrew or Greek word in a sermon is when that word has effectively become an English one already.

Here are some such words I can think of off the top of my head, some of which actually appear in English Bible translations.

- Agape

- Hallelujah

- Hosanna

- Sheol

- Tartarus

- Hades

- Arabah?

- Negev?

- Maher-shalal-hash-baz

If the translation you’re preaching from uses any of these transliterations, you almost certainly need to explain them. I can’t think of anything wrong with doing so. You’re helping people read their English Bibles. (Though I tend to think it is punting for translators to transliterate most words other than proper names. Why should you have to explain them? Why couldn’t they put them into English?)

I happen to believe that agape should not be an English word; I wish it weren’t. Most of the ideas I hear out there about agape are wrong. But it’s impossible for me to explain all that without using the word, so I do.

I might add the names of God and Christ. These feel to me like special cases in which it is truly beneficial to understand the interplay between Hebrew and Greek, Old Testament and New. So:

- Messiah

- Christ

- Jesus

- Elohim

- Yahweh

A well-rounded Christian probably ought to know these proper names and their meaning (or, in the case of Yahweh, our best guesses as to that meaning).

Conclusion

I am far from devaluing the original languages of Scripture. I use them practically every day. But I think their use needs to be more subtle—more structural and skeletal, less on the surface—for it to be effective rather than counterproductive in a pastoring context.

You’d be surprised how often I use Greek without mentioning it. It helps me spot contextual connections that I can then point out in the English.

And it gives me word pictures. For example: my last name, “Ward,” is a borrowing from the same French root that gave us “guard” (different regions of France, I am told by the History of English Podcast, pronounced the initial consonant differently, hence the difference in English to this day!). So my ears perked up recently when a preacher friend of mine said that “guard the good deposit entrusted to you” was (and I’ll quote him to the best of my recollection) from φυλάσσω [phulasso], a military word meaning to guard.

When he asked for my feedback later (he asked!), I told him that he could have made the same point more safely without appeal to the Greek. He could have said, “Paul wanted Timothy to be like a soldier vigilantly protecting precious valuables.”

No mention of Greek was necessary, no implication that what the word guard “really means” is something military. It isn’t. No more than the English word guard is always something military. Instead, he could have used the metaphor that was baked into the Greek word to provide an idea for a brief illustration, anecdote, or word picture.

Bible teachers: resist, in general, the temptation to mention Hebrew or Greek words explicitly.

Related resources

Small Preaching: 25 Little Things You Can Do Now to Make You a Better Preacher

Regular price: $12.99

Hebrew for Life: Strategies for Learning, Retaining, and Reviving Biblical Hebrew

Regular price: $22.99

Greek for Life: Strategies for Learning, Retaining, and Reviving New Testament Greek

Regular price: $19.99

- David Norton, ed., The New Cambridge Paragraph Bible with the Apocrypha: King James Version, rev. ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), I:xxxiv.