One of the greatest threats to our study of the Bible is our familiarity with God’s Word. When we believe we already know something, we tend to stop laboring to understand it.

Familiarity thereby breeds presumption. And when presumption reaches full term, it births unfounded dogma. Then with enough repetition, such dogma takes unassailable shelter in a generation’s consciousness.

For example, did the resurrected Jesus walk through a wall? And did that follow a public ministry that had gone on for three years? Was the person who first ate the forbidden fruit named Eve at the time? Did she do so in a garden named Eden?

If you answered “yes” to any of those questions, you have affirmed something that could be true but is not stated in the Bible. Could your familiarity have blinded you from perceiving what the Bible actually says?

Even when we think we know what the Bible says—as with the commonly studied “one another” commands that we’ll study together in this article, we need to be careful that our familiarity doesn’t prevent us from truly grasping them.

The one another commands

The one-another commands, or more simply, the one-anothers, are the many commands of the New Testament telling people what they ought to do to, for, or with each other. Commands such as:

- “Through love, serve one another” (Gal 5:13).

- “Confess your sins to one another” (Jas 5:16).

- “Encourage one another and build one another up” (1 Thess 5:11).

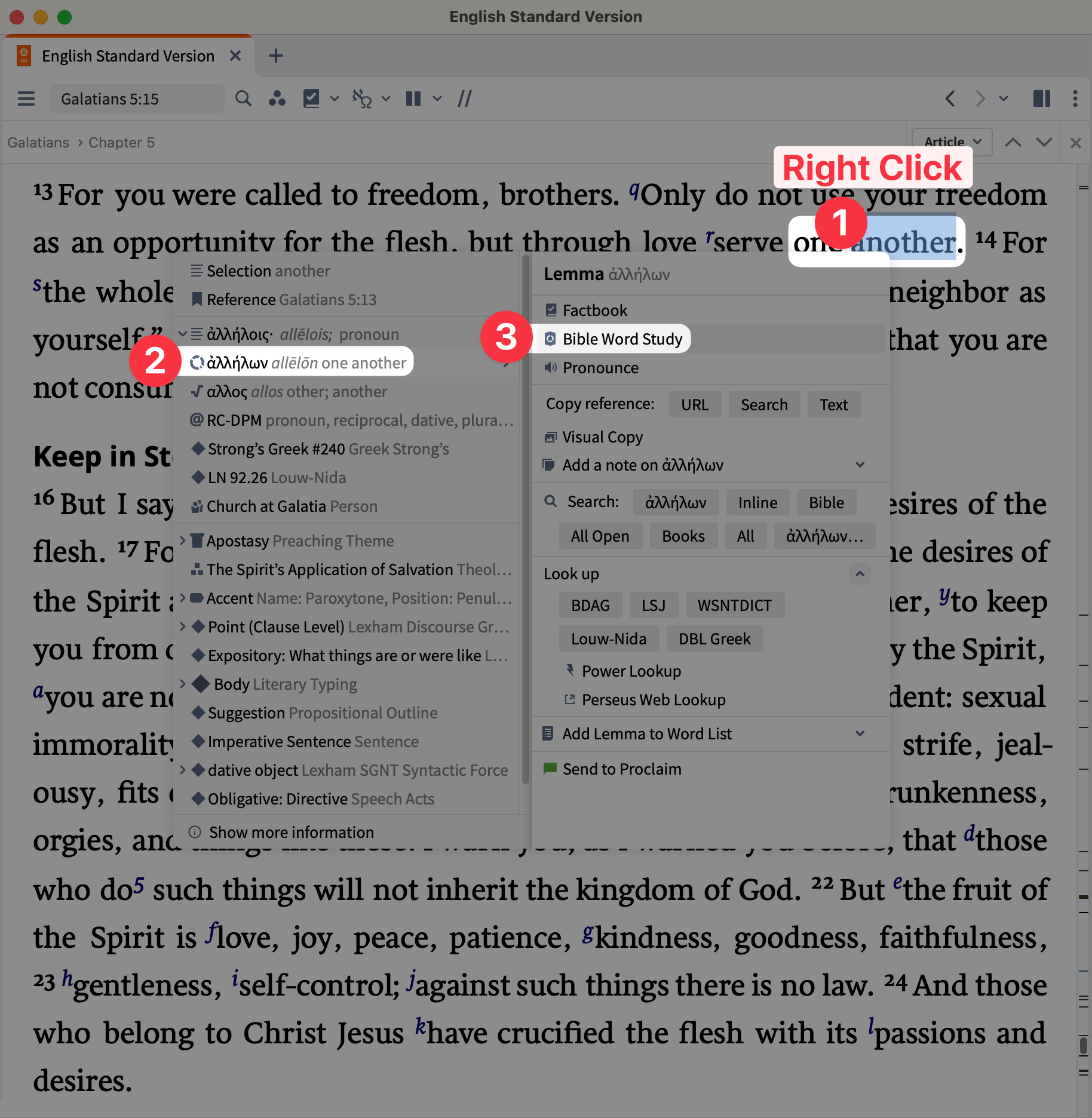

That which is consistent among these commands is the Greek word ἀλλήλων (allelon), commonly translated “one another.” Do a quick Bible Word Study in Logos on this word, following the steps in the image below.

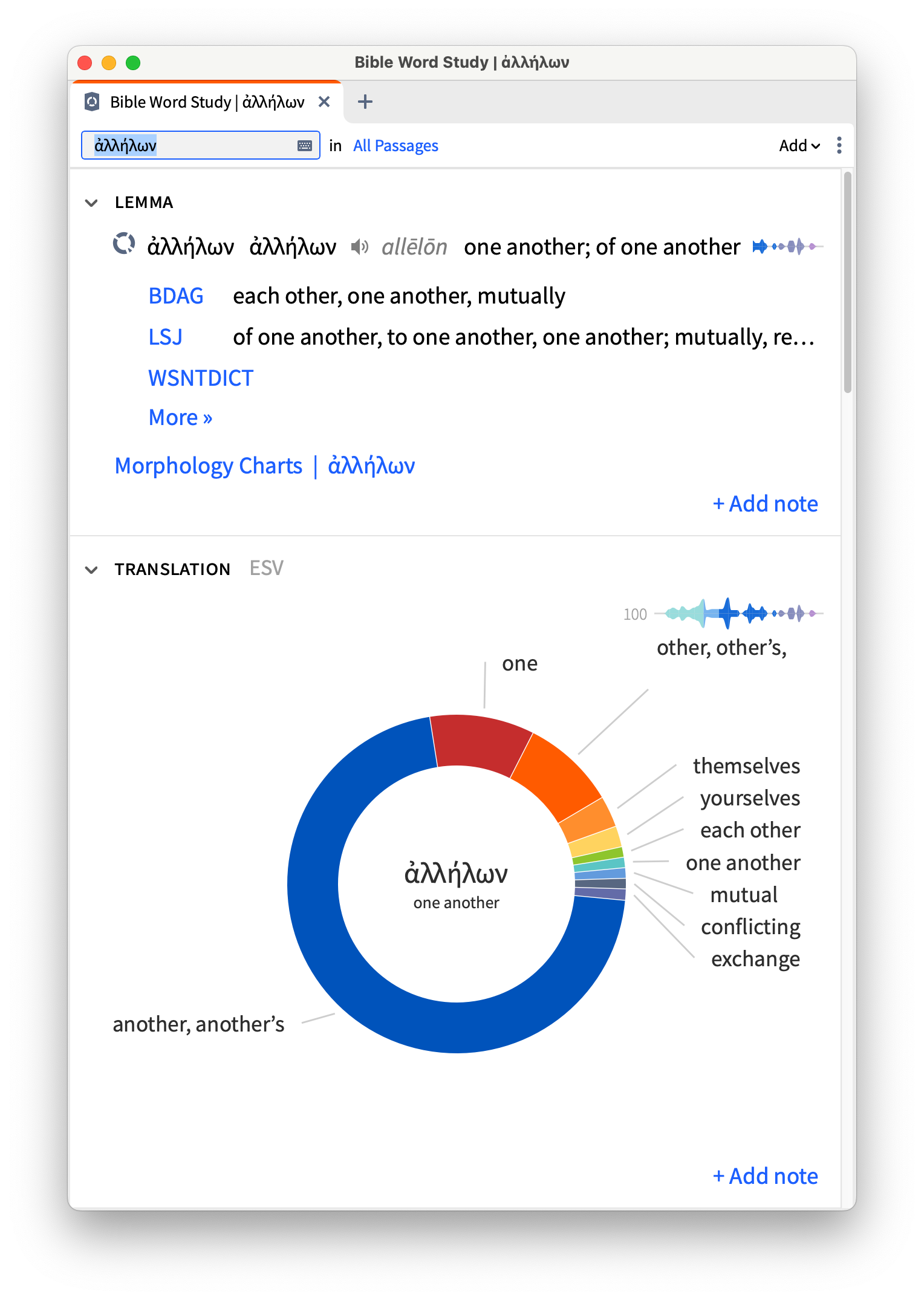

You’ll end up with a list of the exactly one hundred times that the Greek word allelon occurs:

If you read through the list, you’ll see that just under half of those uses involve a direct command. For a helpful visual that covers all the data, see Jeffrey Kranz’s infographic.

The word also occurs twenty-two times in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament—but generally little fuss is made about it there because it never occurs in a direct command. It’s always part of a description or narration, such as:

- kings meeting one another in battle (2 Chron 25:21),

- clouds preventing armies from approaching one another (Exod 14:20),

- or the wings of cherubim touching one another (Ezek 1:11).

The New Testament one-anothers, by contrast, characterize a community reflecting the image of the Lord Jesus Christ: “Outdo one another in showing honor” (Rom 12:10).

They illuminate the wishes of the apostles for the people of God: “Let each one of you speak the truth with his neighbor, for we are members of one another” (Eph 4:25).

In many cases they embody the moral will of God: “Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ” (Gal 6:2).

So how could our familiarity with such commands be any sort of detriment?

The one-anothers and the problem of familiarity

The danger is that our frequent use of the one-anothers causes us to forget what they were for. What each of them was for.

For example: Why did Paul command the Galatians to bear one another’s burdens (Gal 6:2)? Was it because that was part of the abstract body of Christian ethics that he chose to communicate to all people everywhere? Or was there something going on in the Galatian churches that warranted that particular instruction?

Or again: Why did the Hebrews need to stir one another up to love and good works (Heb 10:24)? What sort of good works were in mind, and might there be a time not to stir others up to such things?

Or again: If all Christians everywhere are commanded to be kind and forgive one another (Eph 4:32), what’s to stop an abusive person from manipulating their spouse with an expectation of perpetual forgiveness for unspeakable behavior?

Such commands, in a vacuum and without any context, could be used to support nearly any behaviors one prefers. The command to bear with one another could easily be set in opposition to the command to speak the truth to one another. And each person is left without guidance as to what warrants true peace (Mark 9:50), acceptance (Rom 15:7), or subjection (Eph 5:21).

The problem arises when we put all the one-anothers on a list and treat them as isolated statements, then turn them into a systematic framework for Christian social ethics. We have become familiar enough with the commands themselves that we fail to investigate what the apostles meant by each one.

One last question: Whose concern ought to trump our interpretation of any specific command? For example, John 13:34 presents a command that seems like it should be simple: “Just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another.”

But whose concern determines the proper interpretation or application of that command? Is it Jesus’s concern for his disciples during the Last Supper? Is it the Gospel author’s concern for the people reading his book? Or is it the Holy Spirit’s concern for all Christians in all times and places?

Those three concerns might not be the same.

Overcoming your familiarity with the one-anothers

When we study—and especially when we teach—the one-anothers of Scripture, we must be careful not to collate them as contextless nuggets on a to-do list. The most important question is not, “How can we do the one-anothers?” but instead, “How is the author using any particular one-another to instruct his audience?”

This requires us to treat the one-anothers with care and nuance. Here are four things to keep in mind.

1. Remember that you are reading someone else’s mail

When we read any passage of the Bible, one-another commands included, we are reading something that was written for us but not to us.

The same apostle who commanded, “Do not lie to one another” (Col 3:9), also commanded, “When this letter has been read among you, have it also read in the church of the Laodiceans” (Col 4:16). We know intuitively that the latter command was not written to twenty-first century readers of the Logos blog. It’s difficult, however, to remember that fact for the former command as well.

2. Consider the historical context

What was going on in the lives of both author and audience that led this person to write to these people at this time? How does the one-another command speak into that particular situation?

For example, 1 Corinthians 11:33 issues the following command: “When you come together to eat, wait for one another.” Verse 20 of that chapter clarifies that the “eating” under consideration is the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. The “waiting” has to do with factions in the church exercising superiority over other factions (vv. 18–19, 21). Those factions were identified in the letter’s first chapter as cults of personality (1:11–12). And the “waiting” is something they claim to do for Jesus (1:7) but refuse to do for one another.

Our application of this verse must take this context into account, lest someone think it merely a matter of proper etiquette or social deference.

3. Consider the train of thought

The one-another commands fall within larger passages where the apostles seek to persuade their audience to think, value, or do something. The one-another command itself might not even be the main or most important idea!

For example, the command to “submit to one another out of reverence for Christ” (Eph 5:21) is easy to abuse apart from its context.

That command to submit is the fifth participle—after (1) “addressing,” (2) “singing,” (3) “making melody,” and (4) “giving thanks”—that Paul employs to define what it means to “be filled with the Spirit” (Eph 5:18). The command to be filled with the Spirit is itself a fleshing out of the command to walk in wisdom (Eph 5:15).

And following the command to “submit to one another” is a series of instructions for relationships that involve such submission:

- wives to husbands (Eph 5:22–33)

- children to parents (Eph 6:1–4)

- servants to masters (Eph 6:5–9)

Each of those pairings instructs subordinates to submit and superiors to serve. Therefore “submission” will look different for different people depending on their station with respect to the relationship involved. For example, a man could be in a position of both service to his child and submission to his employer.

According to Paul’s train of thought:

- Walking in wisdom means, in part, being filled with the Spirit.

- Being filled with the Spirit means, in part, submitting to others.

- Submitting to others means, in part, relating to others in a manner befitting your station with respect to them.

Therefore, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ,” is not a general command that applies in the same way to all believers in all their relationships. If you want to be wise and Spirit-filled, you’ll act in a manner befitting the nature of each of your many relationships with others.

Attempting to apply Ephesians 5:21 without grasping the letter’s train of thought would be like trying to conduct a steam locomotive through a trackless pasture.

4. Focus on the main point

Many times, the one-another command is presented as only one possible application of a larger main point.

For example, 1 Thessalonians 4:18 commands, “Encourage one another with these words.” “These words” involve the truth about the coming descent of Christ from heaven and the resurrection of the dead in Christ to be with him. Paul recounts those truths because some people sorely miss their loved ones who have passed (v. 13).

So, “Encourage one another with these words” is a particular application for that community to help their bereaved brothers and sisters. But the main idea is that death, for the believer, is not the end. Our hope in Christ for the future shapes our grief in the present. Maybe you need to encourage others with these words. Maybe you need to be encouraged yourself. Or maybe you’re not currently in a situation where such encouragement is warranted.

Regardless of your situation or that of your community, it’s crucial to have a proper view of death and the future to inform our present.

Conclusion

The one-anothers of Scripture were never intended to serve as a collection of quotable quotes. Nor do they present a one-hundred-step plan to vibrant church life. But that’s often what we’re left with if our familiarity prevents us from wrestling with what the apostles meant by them.

How can you overcome your familiarity with these commands? Remember that you are reading someone else’s mail. Consider the historical context of each author and audience. Consider the author’s train of thought through the full text before and after the one-another. And focus on the main point.

These practices may bring you back to direct application of some one-anothers. But it may also deliver valuable insight into the proper application of many others.