A friend of mine recently polled his church—both members and pastors—to see which Bible study resources they used. Independently, every single one of them named Strong’s Concordance. Many mentioned nothing else. Strong’s was their only Bible study tool.

I’m here to help you understand two things:

- How to use Strong’s Concordance

- Why you should probably reach for better tools instead

I’ll tell you what those tools are, and I’ll mention both free and paid resources. And I want you to know: I will work in good faith in both parts of this article. If you choose to use Strong’s in your Bible study, I’ll show you what to do and what not to do. But I hope you will consider my recommended alternatives.

1. How to use Strong’s Concordance

Here’s how the original 1890 title page describes Strong’s Concordance—gotta love those massive, explanatory, nineteenth-century titles:

Let me explain the elements:

- A concordance is just a list of all the words in a book in alphabetical order.

- Strong’s is a concordance of the words in the common English version, in other words, the translation then used by effectively all English speakers; namely, the King James (or Authorized) Version.

- It’s a concordance, however, of just the canonical books—the canon as understood by Protestants, so no Apocrypha or deuterocanon.

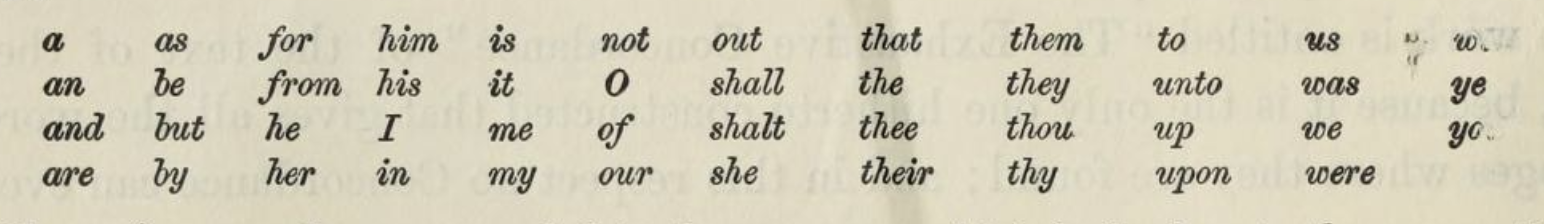

- It’s exhaustive: all the words are there, except for forty-seven words that are so common that they wouldn’t be helpful for the purposes of a concordance—which is (typically) finding passages of the Bible by searching for key words. Here are those forty-seven exceptions:

- Strong’s puts the KJV words it lists in regular order; that means alphabetical order—from Aaron, Abaddon, and Abagtha to Zain, Zechariah, and Zephaniah.

What to do with Strong’s Concordance

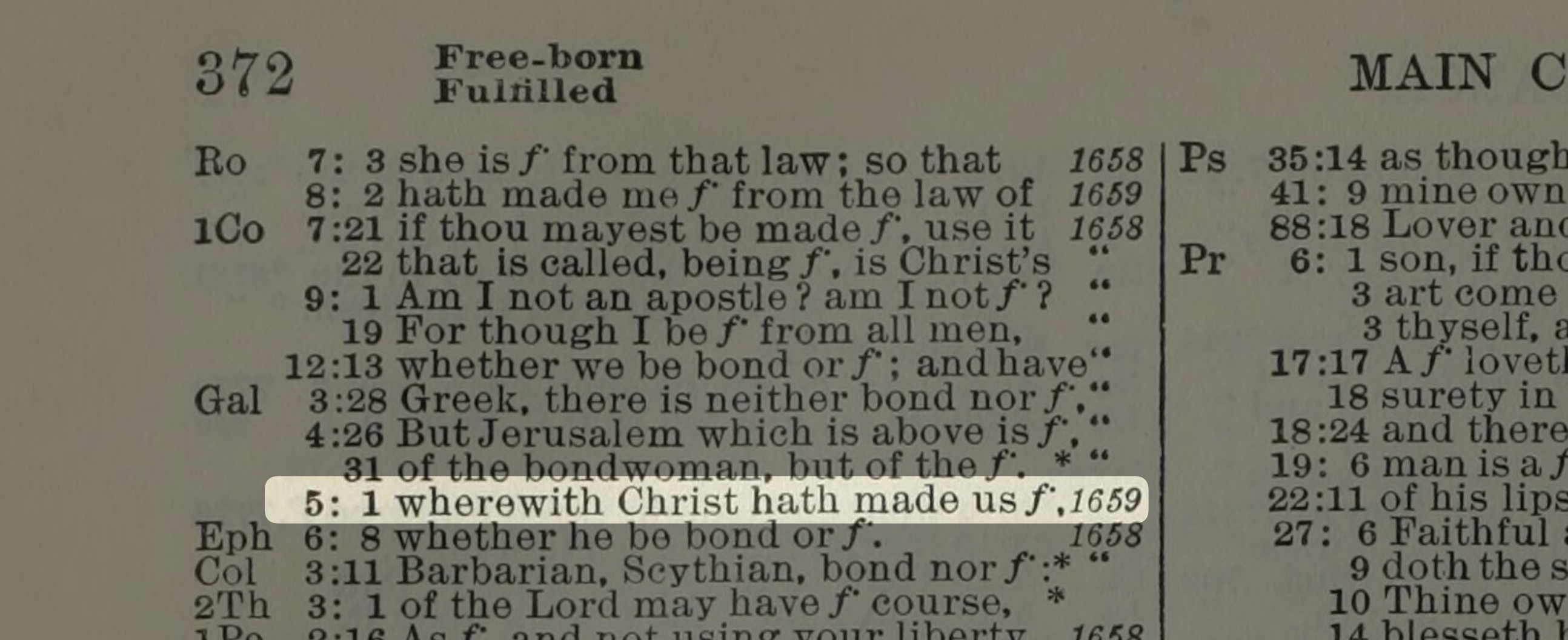

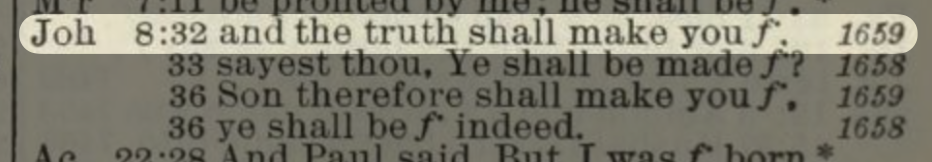

Before tools like the concordance, if you were studying your King James and just couldn’t remember where the phrase “wherewith Christ hath made us free” occurred, you were out of luck. But look up “free” in Strong’s, and soon enough you’ll see this:

Bam: Galatians 5:1. That’s helpful to the paper-oriented Bible student!

And at the end of the line, you’ll see one the other major values of Strong’s Concordance. It’s a number: 1659. That number actually tells you the Hebrew or Greek word (Greek, in this case) that was translated “free” in Galatians 5:1. The Greek word here happens to be 1,659th in the (also alphabetical) list of Greek words in the New Testament.

And that brings us to the next major portion of Strong’s title page:

What you’re supposed to do with Strong’s is find out what Hebrew or Greek word the KJV translators were looking at: the one they chose to translate as “free” in Galatians 5:1. Then you’re supposed to go look it up in the dictionaries in the back of the volume. This is what most people, most of the time, are doing with Strong’s—especially now that Google can help you find whatever passage you remember only a snippet of. Usually, today, when people say they “use Strong’s Concordance” for their Bible study, I think they mean they use the dictionary in it to look up the meaning of Hebrew and Greek words. In many circles of English-speaking Christianity, it is the go-to resource.

And Strong’s is indeed a potentially powerful tool for Bible study. Without even knowing Hebrew or Greek, you can go look up the Hebrew and Greek words of Scripture. You can even see where else a given Greek word you’re studying in one passage gets used (and translated) in other passages. This lexically focused approach is characteristically Protestant—and often fruitful. It’s powerful for Bible study if you know what you’re doing.

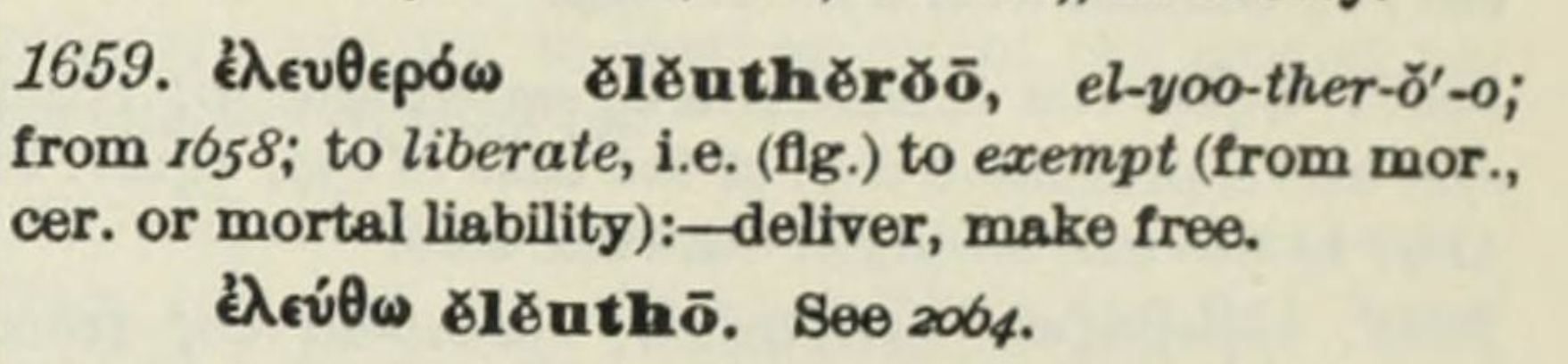

So let’s do it. Let’s look up G1659 and see what we find in Strong’s “brief” dictionary in the back of the massive volume. This is what we find:

Let me break down the elements of this entry.

- 1659 is the “Strong’s number” assigned to the Greek word we’ve just looked up.

- Then comes the Greek word itself, ἐλευθερόω, in Greek letters. This is likely to be little help to most users of Strong’s—because it wasn’t designed as a tool for those who know Greek or Hebrew. So what follows is a transliteration with pronunciation helps: ĕlĕuthĕrŏō, and then another transliteration with even more pronunciation helps: el-yoo-ther-ŏ´-o. (The acute accent mark [´] shows which syllable to stress.)

- What comes next is less helpful, in my opinion. Strong’s tells you the etymology of the word we’ve just looked up. It’s “from 1658,” which is easy enough to look up, because it’s the previous entry. It’s just the noun form of this verb. That word, in turn, says it’s from Strong’s 2064, which is the word “come.” I don’t see how this helps anyone. My honest advice in this how-to—and I’ll explain myself a little more later—is that you skip the etymologies in Strong’s. They will rarely tell you anything useful to actual Bible interpretation, and when they seem to tell you something useful, that something will very likely be wrong. A word’s history is no sure guide to its present meaning, or “December” (from the Latin decem, meaning “ten”) would be the tenth month, not the twelfth; and the “true meaning” of my name, Mark, would be “The Roman god of war.”1

- Now we get to the meat on the dry lexicographical bones: a definition! “To liberate,” Strong’s says. “i.e., (figuratively) to exempt (from moral ceremony or mortal liability).” This is what Strong’s calls “applied significations of the word, justly but tersely analyzed and expressed.” This is what the Greek word means when used in the New Testament, as expressed in a few synonyms and (incredibly brief) explanations. This is what most people are after when they look up a Greek or Hebrew word, and this is what Strong’s delivers.

- Finally, we get two more words that may mildly confuse anyone who didn’t read the fine print at the beginning of the dictionary: “deliver, make free.” These are not definitions or synonyms; they are what are called “glosses.” These are the words actually used by the KJV translators to translate this word. They chose “deliver” in Romans 8:21 and “make free” in the six other places this word occurs in the New Testament.

So now what are you supposed to do? What are you supposed to make of all this? Three suggestions:

- Strong’s gives you quick-and-dirty “glosses”—translated equivalents in English—of Hebrew and Greek words, and that’s useful in a pinch for Hebrew and Greek students who don’t have better resources at hand.

- Those glosses should, in almost every case, simply confirm, strengthen, and establish what you already know from English. (More on this in the section below.)

- If you don’t know any Hebrew or Greek, but you do have a sense for what counts as a literal/formal translation and what counts as a dynamic/functional one—like “they shake their heads at us” (NLT, formal) vs. “a laughingstock among the people” (NASB, functional)—Strong’s can give you some sense for what’s going on with idioms and figures of speech. Now, the NASB already has a footnote at that passage saying, “Literally, ‘shaking of the head.’” But you can come closer to seeing it for yourself by using Strong’s.

This summarizes the benefits of Strong’s dictionary of Hebrew and Greek. More advanced students of Scripture or of language may possibly use it to survey the usage of a given Hebrew or Greek word and then come up with their own ideas as to what it means. But there are much better tools for this work, as we’ll soon discuss.

What not to do with Strong’s Concordance

I must offer a few warnings here on how not to use Strong’s. These tips will end up being reasons for using different tools.

First, avoid thinking that you’ve discovered “the true meaning” of the word “free” in the Bible. Don’t assume that every time Strong’s word 1659 occurs, what it “really means” is “to liberate from moral ceremony or mortal liability.”

Because, again, what did Strong’s tell you that you didn’t already know from reading Galatians 5:1 in English? Let’s read the verse in the KJV:

Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage. (Gal 5:1)

In context, to which every Bible reader should always stay hyper-alert, Paul is talking about New Covenant freedom from certain Old Covenant expectations.2

So, yes, the word translated “made free” is being used to speak of the freedom Christ has given to Christians to live apart from dietary and circumcision laws. We are free from “moral ceremony.”

But that’s not what the Greek word really means. And let me give two big reasons why I think that’s important enough to tell you:

- You don’t want to develop the idea that only people who understand Hebrew and Greek can know what the Bible “really means,” as if there is a hidden mine of rich meaning that English (or Spanish or Russian or Urdu) Bible readers don’t have access to. Remember: Strong’s didn’t say anything about Galatians 5:1 that you couldn’t know from context in the KJV—or ESV or NASB or NIV or any of a number of the other excellent English Bible translations we have.

- You don’t want to import meaning improperly from one context into another. The next move Bible readers are often tempted to make is to take the “real meaning” of a given Greek word and read it into other passages in which that word gets used. Look back at the entry for “free” in the Concordance, and you’ll see that Strong’s number 1659 pop up again in places like John 8:32, in a famous phrase:

When Jesus said, “the truth shall make you free,” what did he mean? The temptation is to say, “Aha! He meant to make you free from moral ceremony!” An excited preacher or small group leader might immediately scribble down some “insights from the Greek” to share with his or her group. And that preacher or leader might say, “Jesus was promising to make his Jewish hearers free from moral ceremonies!”

But in every instance in which that Greek word occurs, including John 8:32, the context specifies what it is that people are being freed from. And John 8 is no exception. Jesus soon clarifies that he means his hearers are “slaves of sin.” That, in context, is what the truth will free them from.

This may seem minor, but I’ve seen well-meaning Bible interpreters fall off the proverbial wagon this way. They get all jumbled up. Instead of focusing on what their very carefully constructed English translations are already clearly telling them in their own language—putting gold right on the surface of the ground, as it were—they get fascinated with this supposedly hidden layer of meaning in the Greek. But what they come out with is that other kind of gold, the one it would be offensive to name. You know—iron pyrite.

This is hard to say and, I’ve come to find, even harder to hear: most of the insights I see people derive from Strong’s are wrong. Not horribly wrong, not heretically wrong, just linguistically and hermeneutically wrong—which is wrong enough.

2. What to use instead of Strong’s

So what resources should you use instead of Strong’s Concordance? I’ll talk through several categories.

English

Honestly, my first replacement is that you stick with English. There are so many great Bible dictionaries and commentaries that use only the language you already know. Use multiple good English Bible translations, gain some sense for why they differ, and you may actually do better than someone who likes to ride the sacred cow of original language usage through the slaughterhouse of linguistic fallacies.

- Pick up the Lexham Bible Dictionary, which comes free in the free version of Logos. Any concept you want to study in Scripture is probably better studied through dictionary entries than through use of languages one does not truly understand.

- Grab the famous InterVarsity Press “black dictionaries,” a set of detailed Bible dictionaries that focus on individual portions of God’s Word and are written from an evangelical perspective.

I know it seems odd for an employee of Logos to point even a single person away from Hebrew and Greek and toward English. I love these languages—would that all the Lord’s people were Greek and Hebrew scholars! The more the makaroi! But we should not underestimate the capacity of English to express what is in the original languages. By all means, learn to read your Bible in Greek or Hebrew. But learn also to read it in English.

Logos Bible Word Study tool

If you do wish to push ahead into using Hebrew and Greek, my next suggestion is that you start with Greek, and that you set clear goals for yourself by picking up this free guide I wrote.

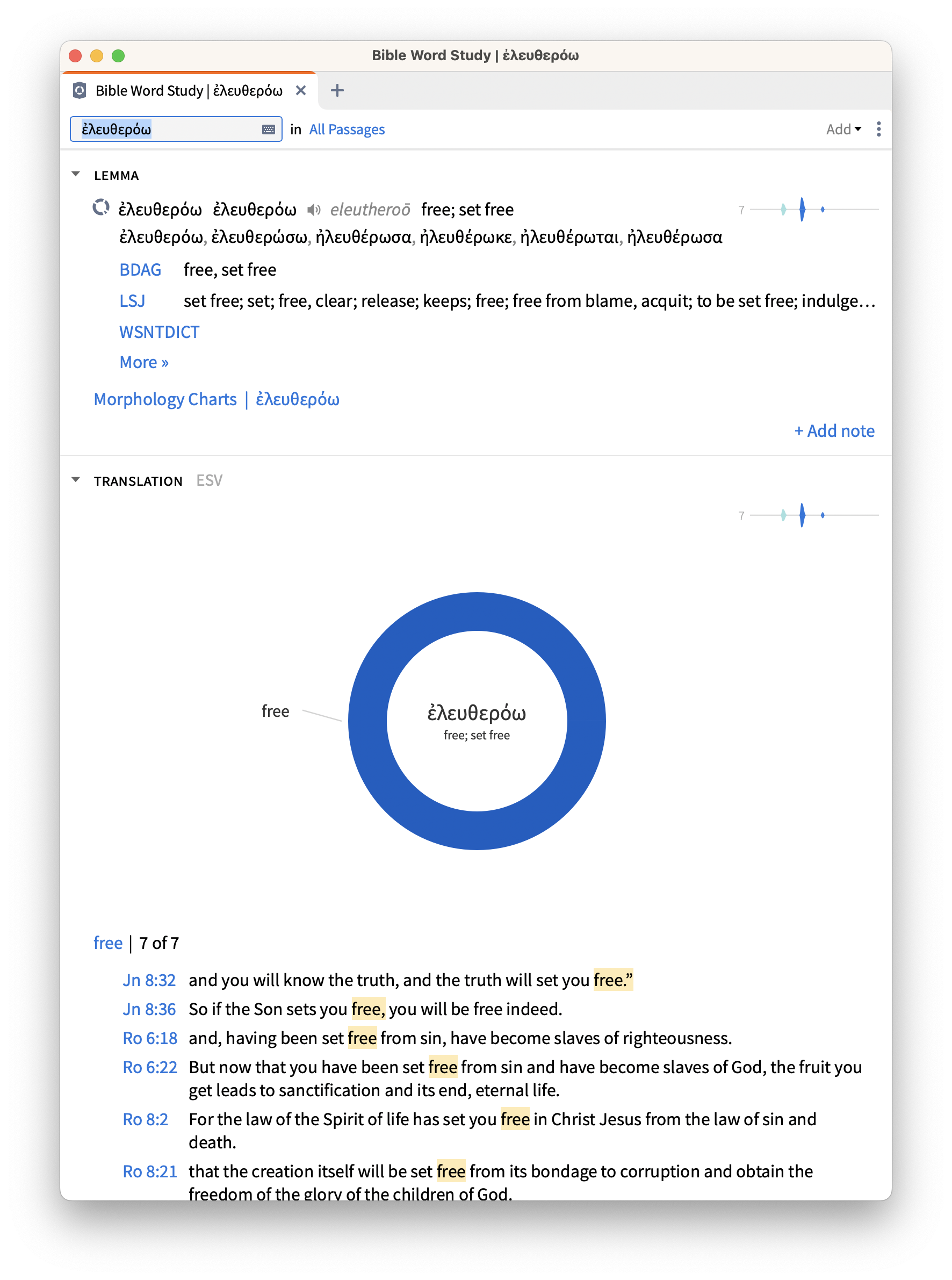

Then I encourage you to use the same tool I use all the time, the Bible Word Study tool in Logos. If you take a little time to go through D.A. Carson’s excellent little book, Exegetical Fallacies, for example3, it truly is possible to gain insight from Hebrew and Greek without knowing them. All you have to do to replicate—and massively exceed—Strong’s Concordance is right click on any English word in any major English Bible translation, and Logos will give you access to tools for studying the underlying Hebrew or Greek word(s) at that place.

What you get is not only a concordance more powerful—and rapid—than Strong’s, but you get multiple tools for looking at how a given word is used. And they’re beautifully designed and arranged. I have used this tool literally thousands of times. I use it to do the kind of study that lexicons do.

And if you get stumped, the Bible Word Study gives you access to whatever original language dictionaries you own. Let me talk through a few of those.

BDAG and BrillDAG

BDAG—Bauder, Danker, Arndt, and Gingrich—is the top Greek-English dictionary. Its definitions are sentence-length descriptions, not merely one-word glosses. For example, for the first sense of that same Greek word for “trust,” it offers this definition: “to consider something to be true and therefore worthy of one’s trust.” That’s a restrained, careful description that actually fits the contexts in which the word gets used. And BDAG gives four other senses that are equally careful, along with various example passages in which they appear. Reliable resources don’t dunk you into a meaning soup; they give you some guidance on which sense of a word might be present in a given biblical context.

BrillDAG, the Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek, is a more recent competitor—or, I’d say, supplement—to BDAG. Its purpose is a bit different, and its definitions and citations are not as extensive. But it’s reliable and careful.

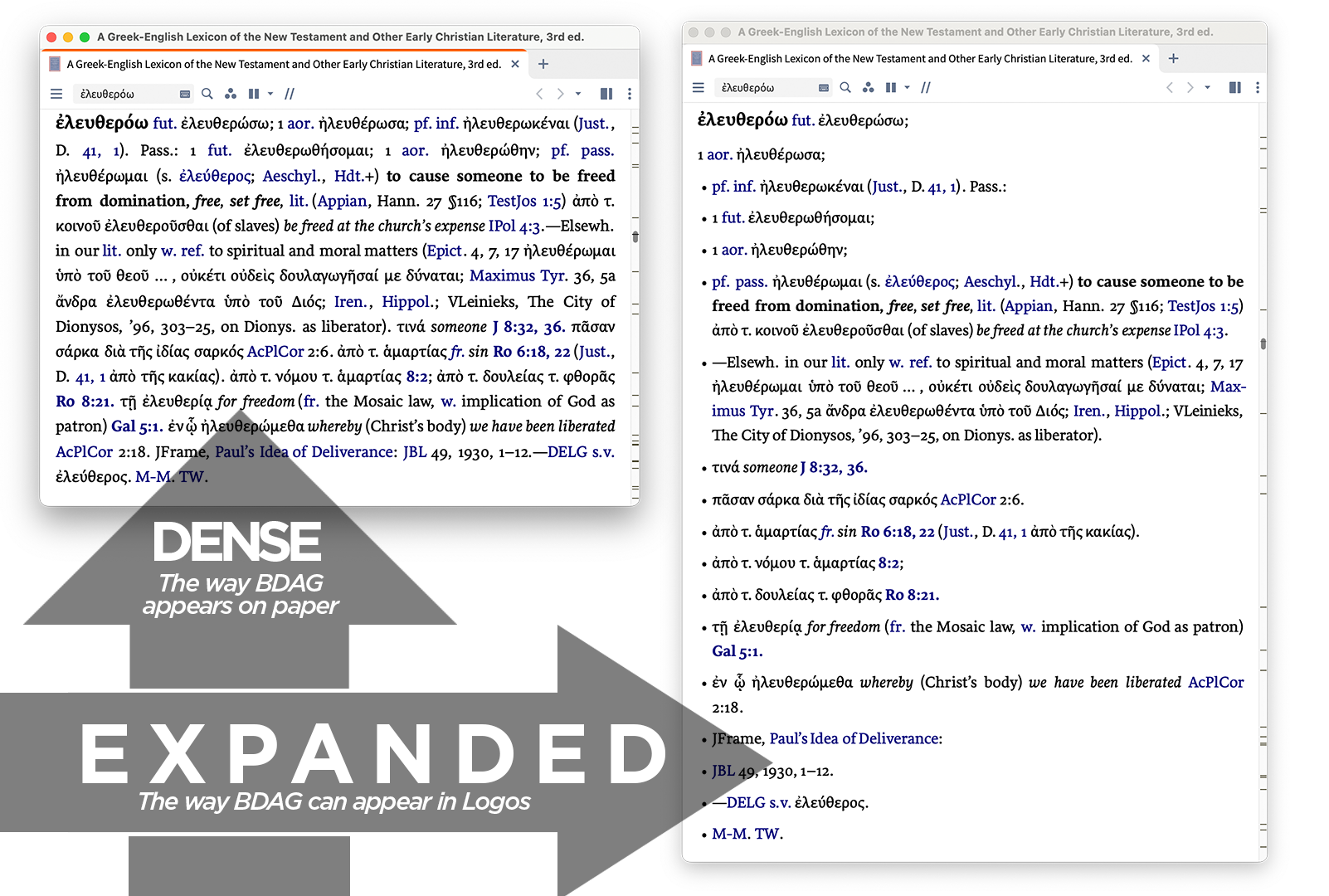

Both of these “lexicons” (the academic word for dictionaries) are much easier to use in Logos than in print. Not only can you look up words instantly with a click, using only an English Bible, but you can—and absolutely should—set them up to display their entries automatically “expanded,” so that you’re not wading through a dense thicket like you would on paper. I find the dense entry below difficult to wade through; I love the expanded, outline format:

Both of these lexicons would be difficult to use without the ability to read Greek, so, at the very least, learn the alphabet and some basic vocabulary so you can follow the argument.

Dictionaries of “semantic domains”

I also use Louw-Nida and Swanson in Logos; both use “semantic domains” to arrange meaning into categories in a way that helps you play synonyms off each other. The Lexham Theological Wordbook is also worth a look. It carefully distinguishes the different kinds of contexts in which important words get used.4

BDB and CHALOT

For Old Testament Hebrew, the standards are the following:

- HALOT, which is very complex and demanding

- CHALOT, a concise and therefore easier-to-use version of HALOT

- BDB, an older but still useful work

Commentaries

And that actually brings me back to English. Because I think the tools I’ve just recommended will cause some Bible students to rise to the challenge contained within them—but that those tools will bring most Bible students, ultimately, back to English.

There’s no way around the difficulty here, only through it:

On the one hand, I believe wholeheartedly in the value and importance of Bible study for all Christians, and I want to put as many useful tools in their hands as I can.

On the other hand, some of the finer details of Hebrew and Greek are not directly accessible to all Christians. It is not elitism to say this; it is simply true.

The best way for most Christians to access Hebrew and Greek details is usually through the mediation of gifted, trained teachers (à la Eph 4:11). And their work is available mostly in commentaries. Part of me hates sending those who want to do their own original language study to commentaries instead. And, I repeat, I would love to see more people studying Hebrew and Greek! But I do think that the healthy impulse that leads people to pick up Strong’s Concordance will ultimately lead the humble, faithful Christian to the kinds of resources that use Hebrew and Greek humbly and faithfully on their behalf.

Here are the tools I recommend to those Bible students:

- The NET Bible is an excellent study Bible for the word-nerdy, for those who want to peek behind the curtain and see biblical scholars at work on the translation of the Bible.

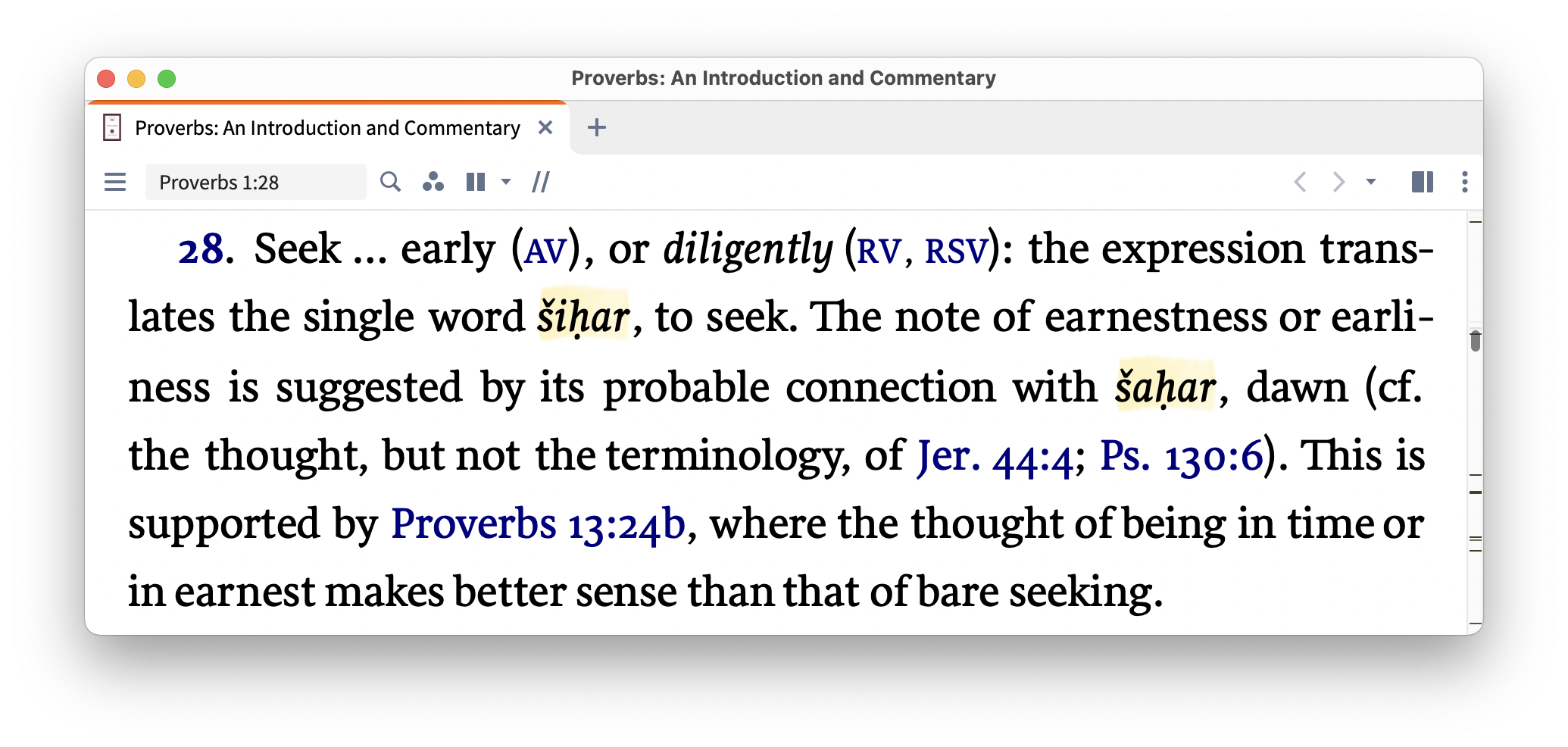

- The Tyndale Commentaries do an excellent job of using the original languages in an accessible way. They’re transliterated into English letters, and used sparingly. Here, for example, one of my favorite commentators, Derek Kidner, cites Hebrew words in a way that even those who don’t know Hebrew can follow:

- The Bible Speaks Today commentary series is similar to Tyndale. One of its major contributors, John Stott, has written some especially beloved volumes in the series.

- The Pillar New Testament Commentary is somewhat more demanding than the previous two, making it a good stretch goal. This series also transliterates Greek and Hebrew words for easier accessibility.

I really could go on and on about commentaries. But one of my best friends—the person I turn to for commentary advice—has written “The Definitive Guide to Bible Commentaries,” and that would be a good place to follow up on this article.

I honor—I love—the impulse that sends Bible students to Strong’s. I offer my advice here with the prayer that the Lord would bless your Bible study, that “our God will make you worthy of his calling, and by his power fulfill your every desire to do good” (2 Thess 1:11 CSB).

Related articles

- The Definitive Guide to Bible Commentaries: Types, Perspectives, and Use

- 7 of the Best Exegetical Bible Commentaries

- 29 Bible Study Tools for Reading the Bible More Effectively

- The Books of the Bible: Your Startup Guide

- A live example: just after I sent this article to my editor, a viewer of my YouTube channel mentioned to me that the Greek word proskuneo, commonly translated “worship,” originally meant something about dogs licking people’s hands. This felt bizarre to me, and I inquired as to his reasoning. He’d gotten this from Strong’s dictionary, which says that “from 4314 [pros, meaning “to the”] and a probable derivative of 2965 [kuon, meaning “dog”] (meaning to kiss, like a dog licking his master’s hand).” This etymology is both (1) almost certainly false (etymologists aren’t sure where kuneo comes from), and, if true, (2) almost certainly irrelevant to the use of proskuneo in the New Testament. I am willing to call this a clear error in Strong’s dictionary.

- A great resource to help you check the context is the Lexham Context Commentary, which says here, Paul’s Hagar-Sarah allegory (4:21–31) has just reminded the Galatians of their identity as gentile Christians: they are the free children of Sarah, the free woman. Now he spells out for them the implications of this freedom: (1) They should fiercely protect this freedom, refusing to submit to the circumcision teachers’ instructions to become circumcised (5:1–12). If the Galatians are circumcised, they will cut themselves off from Christ and his freedom (5:2, 4)! (2) “Freedom” doesn’t mean “selfishness.” The Galatians still need to obey the law’s command to love one another, to the point that they are like one another’s slaves (5:13–15). Douglas Mangum, ed., Lexham Context Commentary: New Testament, Lexham Context Commentary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020), Ga 5:1–15.

- I list a few other recommended books in this Word by Word post.

- Other Greek-English lexicons worth having if you read up on them include TDNT, EDNT, and TLNT.