Chekhov’s gun is a rule of stage drama named after the Russian author and playwright Anton Chekhov. The rule states that if a gun appears in the first act, it must be fired by the end of the final act. “One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.”1 A skilled and conscientious dramatist does not litter his play with inconsequential details that add nothing to the story.

Chekhov’s rule applies to any narrative medium. When you pick up a novel for the first time, it’s common sense that, if you want to understand the story, you should begin reading on page 1. If you open to some point in the middle of the book and begin from there, you will miss much of the setup, plot, and character development that the author intended you to have gained by that point. Although it may be possible to understand the conclusion, you will not fully appreciate the payoff.

The Bible is also a story. It is more complex than a novel because, although it is one book, it is made up of sixty-six individual books, containing diverse literary styles and penned by various authors over many centuries. Yet it forms one unified and cohesive whole told by one divine author. All of Scripture is God-breathed by the Holy Spirit (2 Tim 3:16–17; Heb 1:1–2; 2 Pet 1:21).2

Like a master playwright, God has seeded Scripture with hints and clues about the overarching plot of his great story. These foreshadowing details, called “types,” nudge us along the story as it unfolds. They are his narrative promises to humanity about how history will proceed.

The Holy Spirit is not a sloppy storyteller; he does not make narrative promises that he doesn’t intend to keep. The weird and puzzling rituals of Leviticus or Numbers; the head-scratchingly odd details we find in many of the biblical narratives—these are not meaningless embellishments. They are not mere vestiges of dead ancient Near East cultures that Hebrew writers appropriated.3 They are there to help us understand God’s story more deeply and to magnify of the glory of Christ, who is the fulfillment of all the Law and the Prophets.

In this article we will explore the inner workings of biblical typology. How is typology different from allegory and literary allusion? What makes it work? Typology shows us that God’s revelation in history and Scripture is bound up in Christ, who from the beginning was the Word. Thus, reading Scripture with the eyes of faith reveals to us the majesty of God’s epic story.

Table of contents

Typology, allegory, and allusion in biblical hermeneutics

The word “typology”4 indicates an essential connection between two or more things. The connection between type and antitype is stronger than mere analogy. While “analogy” denotes a similarity between two things, biblical types unfold and develop through history, sometimes over several iterations. By design, they anticipate and point us toward their fulfillment in the antitype.

A clear biblical example of a type can be found in Romans 5:14.

Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come. (Rom 5:14 ESV, emphasis added)

This teaches us that the historical person of Adam was intended to point to and prefigure “the one who was to come,” Jesus Christ. As we read the passage (Rom 5:12–21), we see that while Adam was the first covenant head of the human race who brought death into the world, Christ is our new head in which we have justification and life.

The Scripture sets forward many types of Christ in the Old Testament. Among those most plainly presented in the New Testament we find:

| Type | Antitype | References |

| Adam | Christ as second Adam | Rom 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:21–22 |

| Husband and wife | Christ and the church | Eph 5:22–32 |

| Melchizedek, the priest-king | Christ as great high priest-king | Heb 7:1–17 |

| Earthly tabernacle | Heavenly sanctuary | Acts 7:44; Heb 8:5; 9:24 |

| Moses the prophet | Christ, the greater prophet | Deut 18:15–19; Acts 3:22–26 |

| Joshua (name means “YHWH saves”) | Jesus (Yeshua/Joshua) the victorious | Deut 34:9; Matt 1:21 |

| Israel in the wilderness | The New Testament church | 1 Cor 10:6, 11 |

| Noahic flood | Christian baptism | 1 Pet 3:8 |

Typology

A typological interpretation of Scripture recognizes earlier events, persons, themes, and objects (i.e., types) which God has orchestrated in history to foreshadow and point to something later (i.e., their antitype). Typology is forward-looking. Early revelation points to what will, in the future, be shown more fully. Types may do this through a more direct correspondence (e.g., Joshua led Israel in conquest of the promised land, and Jesus likewise leads his people in triumph over Satan, sin, and death), or they may correspond inversely (by way of contrast)—whereas Adam failed and sinned, Jesus is victorious; while Adam brought death, Jesus brings life.

In their recognition of typology, the authors of Scripture in both Old and New Testaments teach us how we also ought to interpret Scripture.

The types that Scripture explicitly provides us serve as a starting point. They become a guiding framework for us, as examples for how we should understand all of God’s story. In their recognition of typology, the authors of Scripture in both Old and New Testaments teach us how we also ought to interpret Scripture.

Allegory

Biblical typology is related to but distinct from allegory. Allegory simply means to use one thing to speak about something else. As conceived by early church interpreters, allegorical interpretation searches for the underlying theological sense of Scripture. That is, it deals with the doctrinal import that flows from the literal sense, often called the “grammatical–historical” reading. Allegory teaches us what we are to believe about God, and especially about Christ, in every text.5 Therefore it encompasses typology, but is broader in scope.

Many Protestant interpreters of the Reformation, beginning with Luther, were concerned with how allegorical interpretation had become disconnected from the literal meaning of Scripture. These Reformers tended to emphasize the literal–grammatical meaning of the text over more fanciful allegorical readings which had become popular.6

The Reformers did not reject theological and typological meaning in Scripture, but recategorized it under a single “one true sense.”7 In doing so, they sought to root theological and typological reading more securely in the literal meaning of the text.

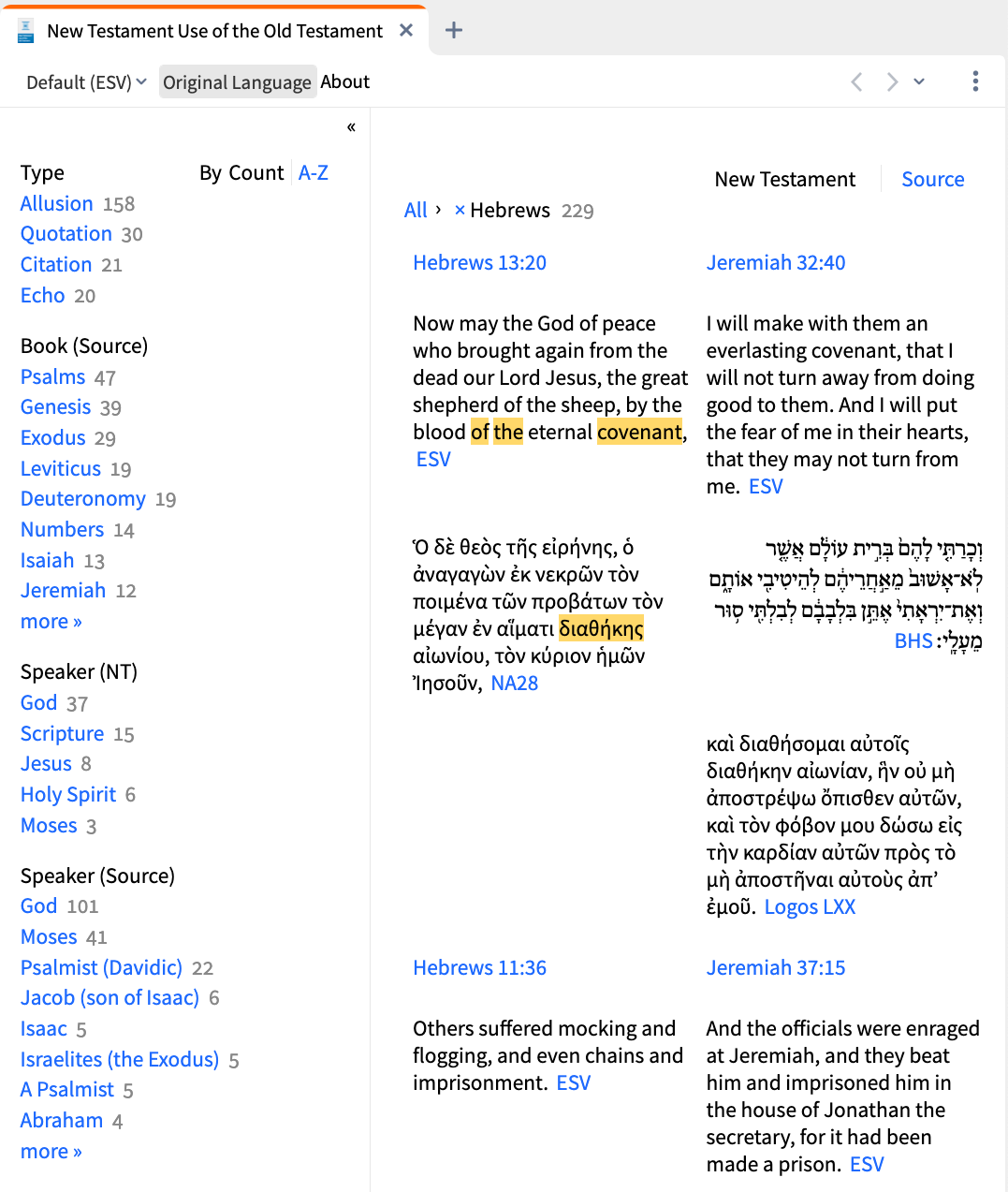

To examine intertextual references in more depth, use Logos’s New Testament Use of the Old Testament interactive media. Learn more about this feature in Logos, if you don’t already have it.

Allusion

Allusion is the inverse of typology. It is a literary feature that involves looking backward. Literary allusions in the text of Scripture show us how writers of both the Old and New Testament have reflected upon earlier Scripture. A biblical writer may recognize how God has embedded a type in the story, and he may therefore allude to it in his presentation of an antitype.

It is possible to recognize allusion while rejecting typology. Those who do not have faith in Christ but who are sensitive to literary patterns will frequently notice allusions. Secular academics may offer genuine insight into the text. However, they may see allusions where none exist, as they mistake God’s actions in history (typology) for a later author’s mere retrospective, thematic borrowing.

Divine authorship

As God’s revelation to us, typology presupposes two basic things:

- God is the author of history.

- God is the author of Scripture.

Types are first historical, and only then literary, as the biblical text recounts actual events. King David of Israel is a type of Christ, not because later authors alluded to him as such, but because God has orchestrated history so that David’s life would foreshadow and anticipate the life of Israel’s Messiah.

Because biblical types are historical persons, events, and things that point forward, typology assumes an intent and purpose to history itself.

Only those who presuppose divine authorship of history and Scripture can read typologically. Because biblical types are historical persons, events, and things that point forward, typology assumes an intent and purpose to history itself. History is not a random sequence of events, but is the handiwork of a master dramatist and storyteller who lovingly weaves hints, clues, and foreshadowing throughout his grand narrative, all of which will pay off in the final act.

Typology as the fabric of God’s creation and providence

Typological approaches to Scripture often focus on Scripture’s Christological dimension, how Scripture points to the person and work of Jesus Christ in his incarnation. The end and fulfillment of all typology is found in God’s eschatological plan, which is summed up in Christ. Even types that are not directly Christological (e.g., bridal types of the church; hovering doves as types of the Holy Spirit; etc.), find their yes and amen in Jesus Christ, as do all the promises of God.

However, we need to be careful. Passing over typological development can make typology appear arbitrary. We don’t want to simply “jump to Jesus.”8 In a stage play, a gun may be highlighted, brandished, hidden, and rediscovered before ever being fired. Along the way, its meaning within the story may develop and deepen. Similarly, biblical types take on life and develop over the course of God’s great story. When we connect types to Christ, we don’t want to skip to the conclusion and miss the richness of meaning in their historical development and progression.

Thus, we should think of typology more broadly as the patterns God has placed in Scripture to teach us about who he is and how he providentially acts, as history marches along to its denouement. These patterns exist even before the entrance of sin and death and the commencement of redemptive history proper.

The typological pattern of the “third day” as exemplar

For instance, in Milestones to Emmaus, Warren Gage traces the theme of God’s intervening actions on “third days” throughout Scripture, with all of them pointing to and culminating in the third-day resurrection of Jesus. Among these many third-day types:

- Abraham received back his only son Isaac as if from the dead on the third day, because Abraham believed God would bring the dead to life (Gen 22:4).

- Jonah goes into the image of death in the belly of the fish, and is spit out onto the land on the third day (Jon 1:17).

- After a three-day fast in dust and ashes, which is a figure of death, Esther and the Jews begin to be delivered from Haman, their adversary and accuser (Esth 4:15–5:1).

God enters into the midst of history—into the very middle of the seven-day week—to bring life from death on third days. In fact, he has always done this since the creation of the world.

The very first third-day type appears even before sin enters the world. When the earth was a lifeless barren rock, God called the greenery of life to rise up from the dust of the earth on the third day. Out of the ground sprang grains and fruits bearing seed (Gen 1:11–13)—seed which returns to the dust in the image of death, to be fruitful and multiply in new life (John 12:24).

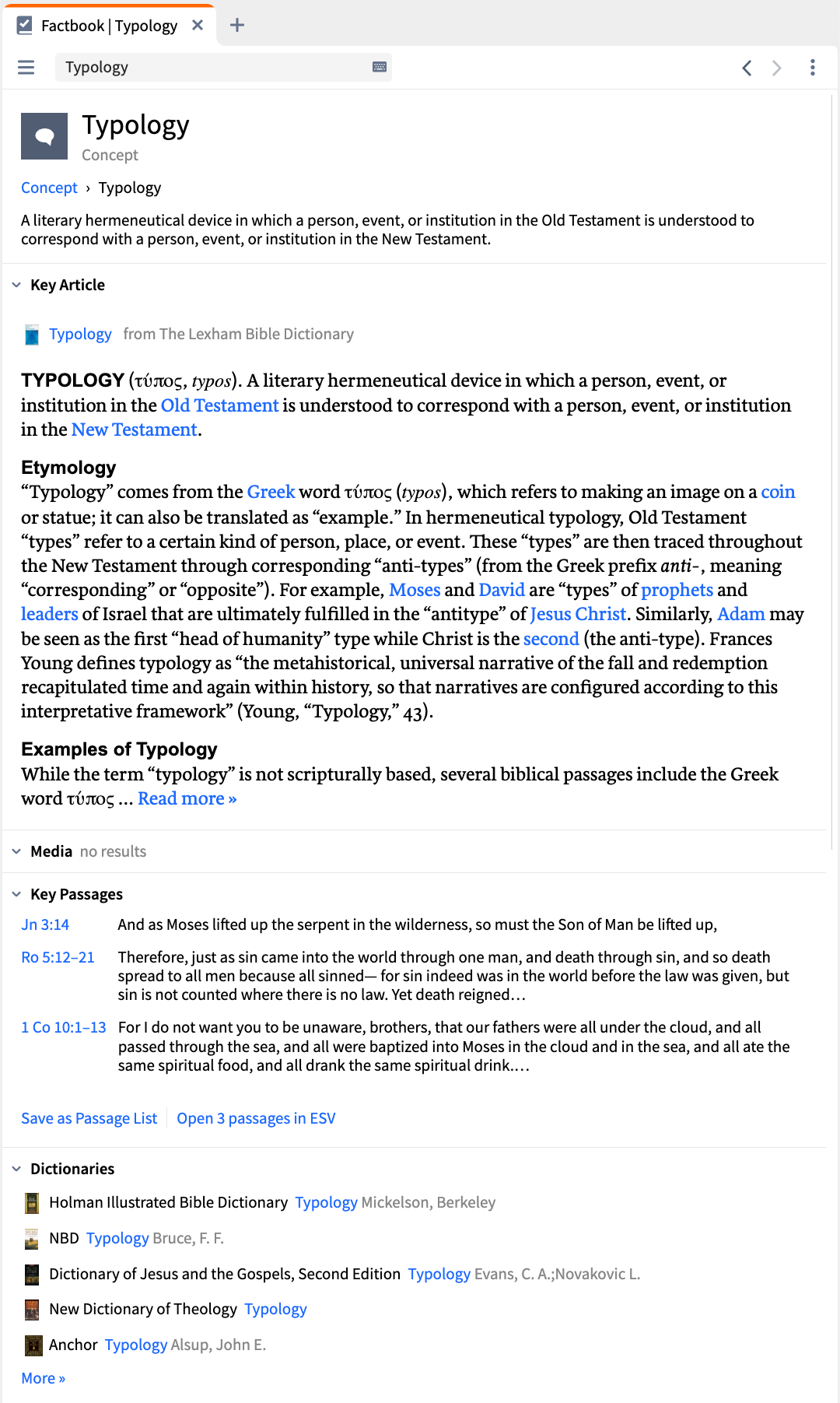

Jump start your own study of typology using Logos’s Factbook tool. Get it free, if you don’t already have it.

Broadening typology as part of creation’s design

While many readers of the Bible recognize typology, particularly when it is explicitly stated in the New Testament, the way it is sometimes applied can feel haphazard or arbitrary. How do lambs prefigure Christ (John 1:29)? In what way does Israel’s temple prefigure Christ’s body (John 2:21)? How does Israel’s crossing of the Red Sea and eating manna prefigure New Testament baptism and the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor 10:1–6)? What are the mechanics of these connections?

Such connections are not arbitrary, but are rooted in the pattern of God’s creation. The whole world is typological because it is God’s cosmic temple (Ps 78:69).9 All types and symbols are derived from the construction of God’s dwelling, where he has created things to represent symbolically other things. Rocks were made to be stable so that they would communicate to us God’s unchangingness (Deut 32:30–31). Gems are not only stable and unchanging rocks, but bright and glorious, in order to show us something more of God’s character. This is why God’s people are to be like gemstones, because they reflect God’s glory (Exod 28:15–21). These become the foundations of the eschatological heavenly city, fulfilling the types (Rev 21:19–20).

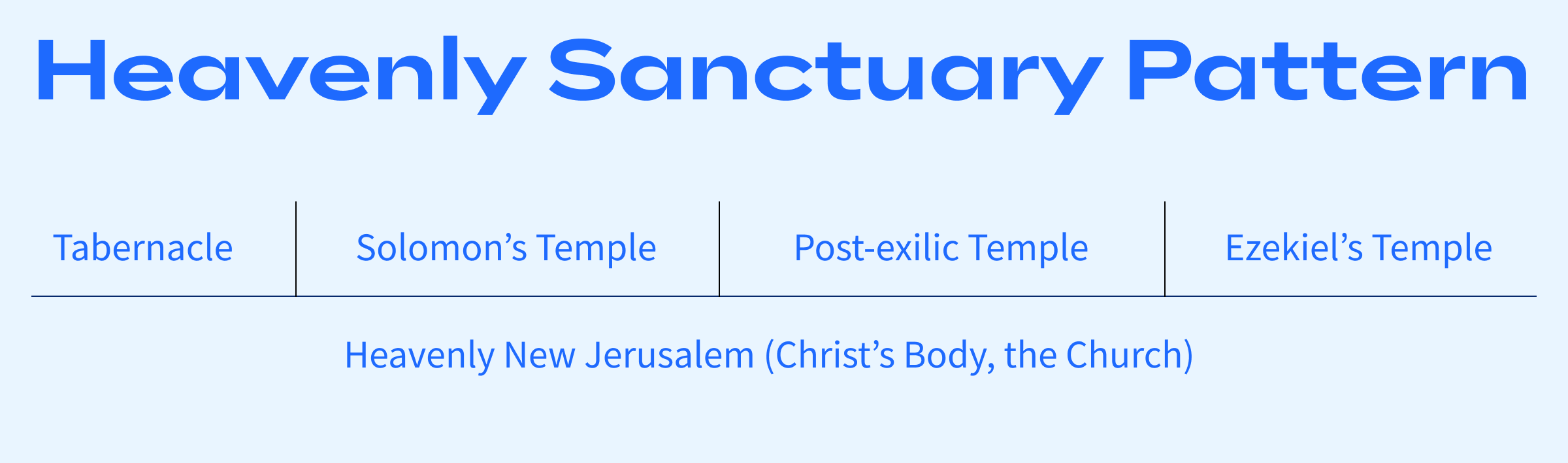

If typology is embedded in the very fabric of the universe, we shouldn’t expect types to function arbitrarily, making random jumps to Christ. God’s patterns are traceable, moving history from one degree of glory to another. The heavenly pattern that Moses saw on the mountain serves as the typological model, not only of the tabernacle, but of each subsequent sanctuary, each more glorious, until the earthly sanctuary is subsumed into the pattern of the heavenly Jerusalem.

When we begin to see the world as a type, we find that everything in God’s revelation points us to Christ and his kingdom. Rocks, fruits and trees, birds and beasts, sun, moon, and stars—all are made to reveal him.10

Jesus, the Word of the Old Testament

John the Evangelist tells us that Jesus is the Word—the logos (John 1:1–18). I don’t believe John is thinking in terms of an abstract Greek philosophical principle of rationality or logic. The concept of logos is drawn from the pages of the Old Testament. It is a New Testament allusion to an Old Testament type.

Jesus is the Word from the beginning. As God works upon his creation of heaven and earth, his first act is to speak. Our God is the God who speaks worlds into being. Yet even before this, the Logos was with God, or more literally “toward” God (John 1:1). In eternity past, the Son faced the Father and was in community and communication with him.

The Word residing among his people

The community of the Trinity provides the basis for God’s communication to us. Thus, we also find the theme of the “Word” in the sanctuary of Israel. The Greek word λόγος (logos) may be related to a name for the holy of holies in the temple (Hebrew דְּבִיר),11 where the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments, literally the Ten Words, resided in the ark of the covenant (1 Kgs 6:16–31; 8:6–8; Ps 28:2).

This indicates to us that the eternal Son, the Word, is the true holy of holies, the manifestation of God’s glory, and the only place we may find covering for sin and communion with God. It fits with John’s declaration that the Word took up residence and “tabernacled” with his people.

This occurred typologically at the giving of the Law at Sinai and through all of their wanderings (Exod 29:46; 1 Kgs 18:31; John 10:35). He went before them in their conquest of the land, defeated Dagon the god of the Philistines in the days of the judges, was enthroned in the temple in the days of Solomon, accompanied his people in their exile to Babylon and their restoration—until he finally came to tabernacle with us fully in his humanity (John 1:14).

From “Urim and Thummim” to “alpha and omega”

If the Word is holy of holies, then he is also Urim and Thummim. When the king or a judge in Israel wanted to know the will of Yahweh in some specific matter, he could go to the tabernacle or temple and inquire of the high priest (1 Sam 14:41; 30:7–8). The priest would reach into the ephod (the high priestly breastpiece) and draw out the sacred lots: the Urim and Thummim. It’s impossible to know exactly what these looked like or how they worked. They may have been something like matched dice, but some texts suggest a more complex system (e.g., Judg 20:18; 1 Sam 10:22).12 Whatever the method, when consulted, the oracle would reveal the will of Yahweh to his people. When we read that Israel, or a king or judge “inquired of Yahweh,” it often means they went to consult Urim and Thummim.

Meredith Kline shows that the garment of the high priest corresponded to the architecture of the sanctuary, with the high priest’s ephod in the position of the ark in the holy of holies (1 Sam 14:18–19; the identification of this “ark” as the “ephod” in LXX is probably correct). With this pattern overlaid, the Urim and Thummim contained therein corresponded to the two tablets of the Ten Words, God’s covenant word to Israel.13

What does this have to do with Logos? The first letter of “Urim” is an aleph, and the first letter of “Thummim” is a tav, which are the first and the last letters of the Hebrew alphabet. In the New Testament Greek this becomes Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last (Rev 1:8; 21:6; 22:13). Urim means “lights,” and Thummim means “perfections,” taking us from the light of the first day of creation to the completion of all things at the end of time.14 The beginning and end of language thus signifies the beginning and end of history.

All of history begins and ends with God’s revealed will, and Jesus Christ is the beginning and end of God’s revelation to us (Heb 1:1–2). The designation aleph and tav, or Alpha and Omega, means that he originates and holds together not only all of eternity and creation, but also, as it were, the entire alphabet—every possible word by which the Father may be revealed. Christ the incarnate Word is God’s self-disclosure, the only way we can know him (John 1:18).15

Typological reading as an exercise in knowing God

And so, typological reading of Scripture is simply this: knowing God through his Son, the Word. Typology works because the Scripture and history have a divine author, whose Holy Spirit inspired its many human authors and guides the course of history. Typology is God’s speech to us, spoken to those who know him, who have witnessed his works of creation and providence.

A faithful reading reads with faith

Typological reading, rightly considered, doesn’t undermine a “plain meaning” of the text, because God does not contradict himself. The types we find in Scripture and the things they teach us don’t contradict the grammatical–historical meaning of a passage, but rather fill it out and deepen our understanding of it.

The doctrine of the “perspicuity of Scripture” teaches us that God’s revelation to us is clear. We don’t need to get access to some hidden knowledge to know God’s will for us or to understand the message of salvation through Jesus Christ. The things of the Lord are hidden from the wise of the world but revealed to little children, not because the message itself is obscure, but because those who see it have been given the eyes of faith (Matt 11:25–27).

Typology presupposes this very relationship of faith in God—it assumes we believe God and are seeking him in his word. When we believe God, he teaches us how to listen. Because the source and goal of typology is Jesus Christ, those who do not believe in him will fail to understand the message.

So we must read Scripture in faith. Only then will the patterns we discover lead us to yet deeper faith and a closer relationship to Jesus Christ. Only then can we understand typology.

Knowing the end, start at the beginning

Audience members who do not notice the brandishing of a weapon in Act 1 can still understand what happens when the gun is fired in Act 3. However, they will have missed some of the richness of the story.

As those who have received and believed in the gospel of Jesus Christ, we have entered the story in the final act. We have taken a peek at the end of God’s book to see if it all works out in the end. Spoiler alert—it does. Jesus wins, and so do you, if you are in him.

But having learned the ending, let us flip the pages back to the beginning, and now read the whole story for everything it’s worth.

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters. And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. (Gen 1:1–3 ESV)

The light has been shining into the darkness since the dawn of creation, and the darkness has not overcome it (John 1:5). That light was the Word of God, the eternal Son from the Father, without whom there is nothing made that was made (1:3). Through him light and life are spoken into being (1:4).

So, let us listen to him speak. Listen for every word, every detail, from the beginning to the end, so that, having already come to know him, we might know him ever more fully.

Recommended reading for further study

Through New Eyes by James B. Jordan

Handbook on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament: Exegesis and Interpretation

Regular price: $24.99

Typology: Understanding the Bible’s Promise-Shaped Patterns; How Old Testament Expectations are Fulfilled in Christ

Regular price: $39.99

Biblical Typology: How the Old Testament Points to Christ, His Church, and the Consummation

Regular price: $19.99

Mobile Ed: BI202 Reading the Bible as a Complete Story (4 hour course)

Regular price: $149.99

Related articles

- What’s Typology? Patterns of Creation in Redemptive History

- The Christological Character of Typological Reading

- Finding Jesus Where He Isn’t: 2 Rules for Typology

- How to Instantly Spot NT Allusions to the OT

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chekhovs-gun.

- The characterization of Scripture’s generation as spiration itself implies a work of the Spirit.

- Though cultural contextual interaction is often present.

- from the Greek τύπος (typos), which suggests the physical transfer of an image or shape from one thing to another (BDAG, s.v. “τύπος”).

- Don C. Collett, Figural Reading and the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2020), 31–32.

- The “literal” and “allegorical” are two of the four classical senses of Scripture recognized in the Quadriga, the other two of which are “tropological” (ethical application) and “anagogical” (eschatological hope). For a concise discussion of this, see Mitchell L. Chase, 40 Questions about Typology and Allegory (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic, 2020), 88–94.

- Collett, Figural Reading, 37.

- This phrase is used by Peter J. Leithart to characterize certain simplistic approaches to typology. “When Gentile Meets Jew: A Christian Reading of Ruth & the Hebrew Scriptures,” Touchstone 20.4 (May 2009): 20–24.

- G. K. Beale and Mitchell Kim, God Dwells Among Us (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2021), 6–17, 47–49.

- In this section I’ve tried to give a brief glimpse of the biblical worldview of creation that James B. Jordan explores at length in Through New Eyes.

- Although the etymology is contested, I believe דְּבִיר has a shared root with the Hebrew דָּבָר, which means “word.” For support, see Matityahu Clark, Etymological Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew (Jerusalem: Feldheim, 1999), s.v. “דבר”; Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Siddur, (Jerusalem: Feldheim, [1969] 1997), 688–89. Although the Septuagint typically transliterates דְּבִיר as δαβιρ, דָּבָר is frequently rendered in the Greek as λόγος (e.g., Deut 32:44–47; Ps 33:4–6; 56–7; 119:105–107; Hos 1:1). This shared etymology also lies behind Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation of דְּבִיר as oraculum.

- C. Van Dam, “Urim and Thummim,” ISBE, Revised (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1979–1988).

- Meredith Kline, Images of the Spirit (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1999), 45.

- R. Alan Cole, Exodus: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries 2 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 1973), 209.

- Philosopher Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy contends that Christ as Word, the Alpha and Omega, suggests that the imperative verb is the primary form of speech from which all other forms must be derived. God must command us to “live” before we can respond, “I live.” God is the one who speaks all things into being and human speech is no different. We must have the Word of God to give us speech. Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, The Origin of Speech (Norwich, VT: Argo Books, 1981), 51–53, 90–95.