Destination: the Eternal City. I was thrilled to finally spend the New Year in Italy with my husband … and a dozen seminary classmates. My doctoral intensive began in Rome, where we sought to discover how the early church celebrated women.

Must have been a short trip, right? What roles could women fill in the church beyond that of wife and mother—especially in the first 1,000 years or so? If they were noteworthy, why don’t we hear much about them? We wondered what the stories would tell us about our callings as Christ-followers today.

Where are the women?

The Bible mentions women who followed Jesus. The Gospels tell us of Mary (Jesus’s mother), Joanna, Susanna, Mary Magdalene, and other unnamed women disciples who followed Jesus and served him out of their personal resources (Luke 8:1–3). Jesus commissioned Mary Magdalene, the first person to meet him post-resurrection, to go and tell his eleven remaining male apostles the good news that he was alive (John 20).

As the fledgling church grew, the apostles celebrated Lydia (Acts 16:13–15), Priscilla, Phoebe, and Junia (Romans 16), along with lesser-known women mentioned in their letters. Though not invisible, few women held leadership positions. Men overwhelmingly possessed authority and office in both society and church.

As such, the written record was largely produced by men, about men, and for men, smothering women’s contributions behind a veil of silence. A few bright lights peeked through: Gregory related the genius of Macrina, while Augustine sang the praises of his mother, Monica. Francis supported Clare’s ministry, and Jerome credited Paula for her help. But in centuries’ worth of spiritual writings, mention of women’s contribution to the church is scarce.

My seminary class crossed the ocean and tramped over ancient cobblestone paths to set our eyes on proof of women’s faithful witness. So, rather than peer down into files full of ancient documents, we stood in dozens of cathedrals—and looked up.

Women in plain sight

“To save your neck muscles, consider packing a small handheld mirror.” Of all the items on our suggested packing list, this surprised us the most. But professor Dr. Sandra Glahn knew from leading multiple trips that we would be craning our necks to view church walls and ceilings.

In the earliest centuries of the church—think second through ninth—church buildings were adorned with sacred art. The average person did not own a copy of the Bible; those rarities were reserved for clergy. Many were illiterate anyway, so church leaders brought the stories of the faith to the masses through mosaics, frescoes, stained glass, and other visual art. Parents could use the visual cues on the walls and ceilings to teach their children about the patriarchs, the judges, Israel’s rulers, Jesus, the disciples, the saints and the martyrs. Sprinkled throughout the artwork, we found a generous proportion of artifacts dedicated to telling the stories of faithful women.

Glahn and co-professor Dr. Lynn Cohick led us through a multitude of churches, ruins, and museums in at least a dozen cities, focused on images depicting women. We trekked from the southern communities of Pompeii and Naples on the Tyrrhenian Sea to the iconic canals of Venice in the northeast. In between, we spent long days traipsing the hills of Rome, Florence, Milan, and smaller, picturesque towns such as Siena, Orvieto, and Assisi. Between slurps of gelato and cappuccinos, we joked that our phones’ fitness apps probably thought they’d been stolen, given our drastically increased step count.

We had stepped into the past, surrounded by beauty that God created and people fashioned. Surrounded by clues to our quest, hidden in plain sight.

What could the visual record tell us about the ancient and medieval church’s view of women?

First, we can know that the early church celebrated women who lived faithfully.

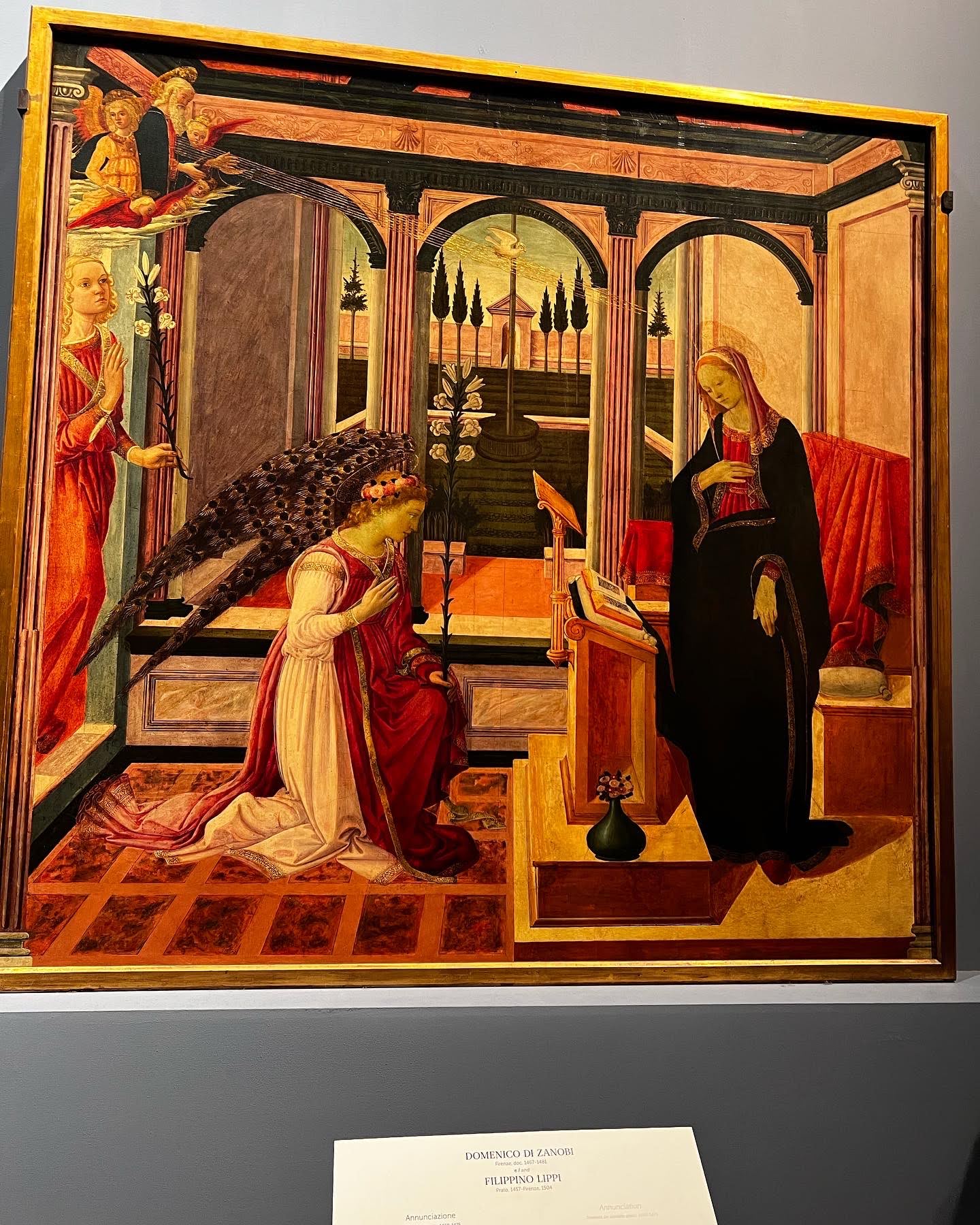

Above all others, Jesus’s mother, Mary, was and remains a favorite. Virtually every Italian town boasts one or more churches dedicated to her, and second only to Jesus himself, she appears in more artwork than any apostle or saint. In the highly favored Annunciation scene (taken from Luke 2 when the angel Gabriel announces to her that God has chosen her to bear the Savior), Mary is most often depicted with a book or scroll, suggesting she was literate. The early church understood that she uttered her Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55) out of a robust understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures. They respected her devoutness, intelligence, and lifelong witness to her son.

In the shadow of Santa Maria Maggiore (St. Mary Major), one of the four massive papal basilicas in Rome, sits the ninth-century Basilica di Santa Prassedes. Tucked among a sea of red-tiled roofs, the comparatively tiny church dedicated to Prassedes (Praxedes) will fool the unsuspecting tourist. The humble façade hides a treasure trove of mosaics, commissioned by Pope Paschal (d. 824), featuring the second-century sisters Praxedes and Pudentiana. These young virgin women served the martyrs of an early persecution, secretly gathering their bodies, cleaning them, and burying them with honor. Pudentiana’s basilica, a five-minute walk down the street, is even older—built in the fourth century. In both basilicas, the apse mosaics present the women as victorious saints, handing their crowns to Jesus, who stands between them. And in the crypt under the high altar of Prassedes lies iconographic evidence from the ninth century affirming that Theodora Episcopa, the pope’s mother, held official church office.

In Ravenna’s Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, we marveled at the long wall of fifth-century mosaics depicting twenty-two female saints, each holding her martyr’s crown. On the opposite wall, male saints are depicted in the same manner.

Among the female martyrs, we saw these:

- Anatolia and Victoria, virgins during the reign of Decius. They refused to recant their faith and died by the sword.

- Daria, a virgin of Athens whose fiancé converted and was baptized. She was arrested with him, and they were imprisoned separately before being tossed in a pit and buried alive.

- Cristina was a young woman whose father had her beaten and imprisoned for refusing to bring offerings to a statue. Her tongue was cut out before she was put in a dungeon with snakes, then bound to a tree and shot with arrows.

- Perpetua, a young mother still nursing her baby, was imprisoned with her slave girl, Felicitas, herself about to give birth (and also depicted in the mosaic). When Felicitas gave birth prematurely, she was allowed to accompany her mistress to the arena, where they died for their faith.

Other women were persecuted for using their financial assets to further the aims of the church rather than the state. Women and their money were supposed to serve their family, but some felt called by God to provide for the poor and outcast. And they suffered for it. A few examples from the Ravenna procession:

- Savina, a third-century martyr and widow of Milan, upon her husband’s death committed herself to helping victims of persecution and was killed for praying at their tombs.

- Anastasia was forced to marry an unbeliever who persecuted her. She disguised herself so she could visit imprisoned Christians and was burned alive for her faith.

- Lucy of Syracuse, rather than marry a pagan nobleman, liquidated her inheritance and gave it away to the poor. She was arrested and commanded to sacrifice to idols but refused and died by a sword through the neck.

Christ gave women agency in an age when society did not. Their witness can give women today courage to step out in faith and obedience in the face of opposition.

Third, the visual record contains evidence of mutuality between men and women in the life and leadership of the church.

The Bible offers us several examples of partnerships between men and women following Jesus.

- In Luke 8:1–3 we learn the names and tasks of the women who accompanied Christ and the apostles.

- In Acts we see Paul join up with Priscilla and Aquila (18:19).

- In his letter to the Romans Paul commends Andronicus and Junia (Rom 16:7), and sends Phoebe, his patron, as his emissary with the letter to the Romans (Rom 16:1).

As we saw in the Ravenna procession of saints, the young church willingly recognized the contributions of women alongside those of men. In a nearby chapel, matching arches featured mosaic portraits of saints’ faces, men on one side and women on the other. We easily recognized the apostles and popes, but the women were less known. Visitors like us found the portraits very helpful for research since they included the names of each person.

In Venice’s National Archaeology Museum, we hunted for a reliquary box, which historically had held saints’ bones. The cover’s ornate ivory panels depict men and women in equal fashion in almost every scene. One panel shows a man and a woman on either side of an altar, under a canopy resembling the one in St. Peter’s Basilica, holding the elements of bread and wine, suggesting to some that both men and women led worship.

In the massive “Last Judgment” mosaic on the western wall of Santa Maria Assunta at Torcello, one plate includes “the chorus of saints”: three groups of men, one group of women. The men wear robes depicting their rank in the church or society, while the women wear a variety of clothing—some in rags, some in jewels and turbans. Their identity has proven a mystery. Deaconesses? Widows? Whoever they are, they all belong to Christ.

What can the faithful women of old teach us about our own faith journeys today?

When we discuss God’s call on his children, men and women, we start with the Bible’s witness. Though outnumbered by their brothers in the text, the women we do know of lived obedient, courageous lives as they pursued God. Some were called to lead and teach and prophesy. They often endured persecution in their own times and, throughout history—including the present—their impact has been minimized. If we close our Bibles and wonder why God doesn’t use women, or believe that he doesn’t, we have not read closely enough.

Likewise, we have not adequately scrutinized our history books or cathedrals. Augustine told Perpetua and Felicitas’s story every year on their feast day—the day of their death. Which of the female saints’ stories have you heard taught in church or catechism? How intentional are our churches to include the testimonies of women in the great cloud of witnesses?

By studying the written and visual record of the early church, we—1,900 to 1,000 years later—can better understand how leaders then understood God’s will for women. God called women. God equipped women. God’s Spirit empowered women. In word and art—but mostly in art—the church retold women’s stories.

To find them, we need only look up.

Related articles

- 11 Christian Women Who Shaped Church History

- Women in Theology: Why the Church Needs Female Theologians

- Bible Truth about Women’s Worth: Live with Elyse Fitzpatrick & Eric Schumacher

- Logos Live: Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson on Women in the Mission of the Church

- Why Did Jesus Appear to the Women Instead of the Disciples?

Related resources

Women in the Mission of the Church: Their Opportunities and Obstacles throughout Christian History

Regular price: $24.99