Nearly a third of high school girls in the US confessed to contemplating suicide,1 a 60 percent rise in the last decade. Young women are experiencing tragic levels of emotional trauma, physical abuse, and sexual violence. One of the primary culprits? Social media—an easy means for constant comparison driving a sense of inadequacy, and by which predators, bullies, and insecure classmates can victimize others.

The pernicious lie of our culture is “you are not good enough.” But God says differently. He fashioned us as the pinnacle of all creation—his image, or icon, representing him on the earth to accomplish his purposes.

Let’s read Genesis 1:26–28:

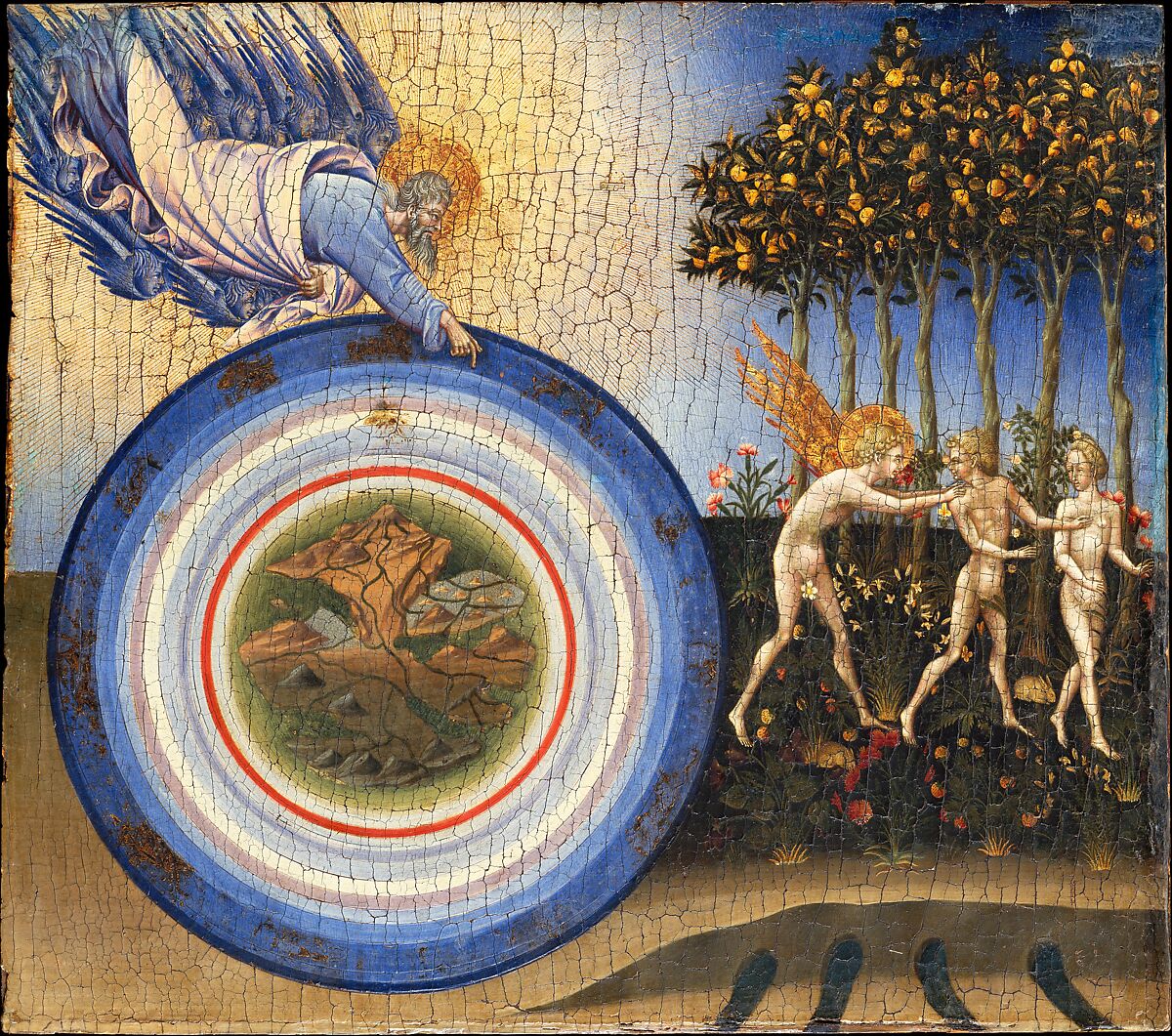

Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.” So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it.

We are family

The image of God is an indelible identity marker of humans. We often refer to ourselves as “image-bearers” or as having been “created in God’s image.” These phrases serve us well enough, but God’s image is not truly something we carry or wear. It’s something we are. In her new work, Being God’s Image, Dr. Carmen Imes writes, “Although our status as God’s image may lead to certain actions, ‘image’ is not something we do, but who we are.”2

Partners

In the Genesis 2 creation story, the man realized he did not have a counterpart in the way the animals did. The man’s aloneness is the only thing that prompted God to describe his creation as “not good” (2:18). When the man awoke from his deep, supernatural sleep and saw the woman, he knew she was like him:

The man said, “This is now bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called ‘woman,’ for she was taken out of man.” (Gen 2:23)

Even in the Hebrew word for man (ish) and woman (isha), we see the wordplay the man was using. She was his counterpart, another human, made from his own essence. Despite her physical differences, he discerned her sameness with himself. His words reflect the narrator’s description of creation in Genesis 1:27,

So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

Only when the woman joins the rest of creation is it “very good” (Gen 1:31). With his icons—his representatives or regents—in place, God launched them into the world to rule and reign on his behalf.

Permanently

Perhaps you’ve heard that sin has defaced or damaged the image of God in humanity. Not destroyed it completely, but so messed it up that we no longer resemble God very closely. Our character has been blackened, darkened, so that his glory no longer shines brightly except possibly from those who are very holy. But such an understanding locates imago dei in our character, not our very identities.

The word “image,” the Hebrew tselem, refers to concrete idols made as icons of the god they represent and placed in a temple. In Genesis, the earth is God’s temple and humans are God’s tselems, his icons. The man and woman are made as God’s image—physical representatives of a spiritual deity. When he placed them in the garden as his representatives, he gave them his authority over every living thing and commissioned them to rule and subdue creation.

We are what we are: icons of our Trinitarian God whose task is to glorify God through our work. The permanence of our identity has repercussions in the way we relate to the world and to one another.

Relating to the world: work as worship

The man and woman were granted dominion over all the other creatures and plants on the earth. They were—and we are—God’s regents tasked with making the earth thrive. Imes again: “Because God rules the world, our representative role includes ruling on God’s behalf.”3 We express our identity as God’s image through what we do. Whether we do it well or poorly, in a holy manner or with selfish motives, does not affect our identity. Rather, our actions affect our witness to God.

God made work to be good, a calling rather than a curse, and a spiritual exercise. Vocation is worship, no matter how mundane. “Ruling responsibly over the creatures God made is the way we exercise our status as God’s image,” writes Imes. “It fulfills our purpose.”4 When we use the talents, gifts, personalities, and contexts in which God puts us to serve the good of the earth and the people on it, God is glorified.

Humanity has not always lived up to its calling, of course. We have abused the earth in micro and macro ways. One of the prophets’ complaints to Israel related to their ignoring the year of rest commanded in Leviticus 25:4, “In the seventh year the land is to have a year of sabbath rest.” Israel did not honor that command, which not only would have indicated faith that God would provide but would also have given the soil appropriate time to recover needed nutrients. Instead, they plundered the ground through unwise and greedy agricultural processes. Hundreds of years later, God sent his people into exile and gave the land its rest: “The land enjoyed its sabbath rests; all the time of its desolation it rested, until the seventy years were completed in fulfillment of the word of the LORD spoken by Jeremiah” (2 Chr 36:21).

Let’s not scoff too quickly at the Israelites. In the centuries since then, societies have sacrificed the earth and its creatures in pursuit of prosperity. In the last century alone, strip mining, overgrazing, overuse of pesticides, inhumane mass poultry and cattle production, excessive deforestation—these and other profitable practices have wreaked long-term harm on our environment. We have forgotten that we are stewards and have acted more like presumptive and short-sighted owners.

We live in a Genesis 3 world in which the earth resists easy cultivation. We feel the consequences of sin with every rock-filled field, devastating hurricane, and viral disease. Nature works against us. But our call remains—to fill the earth, subdue it, and rule over every creature. And so we do, using our intellect, creativity, strength, technology, and cooperation to discover and improve our stewardship of creation.

Community gardens. Technological inventions that improve efficiency. Recycling. Planting trees. Harvesting natural resources for medicinal help. Civil engineering. Medical advances that promote healing and cures for diseases.

Good stewardship isn’t just farming. The late Old Testament scholar Michael Heiser described the cultural mandate this way: “Any task performed to steward creation, to harness its power for God’s glory and the benefit of fellow imagers, and to foster in the harmonious productivity of fellow imagers, is imaging God.”5

When we choose good and pursue God’s ways of ruling, the world thrives and so do we. Living into our identity leads to life for us and all we connect to. God was pleased when he made the world; it reflects his glory. Psalm 65:8 says, “The whole earth is filled with awe at your wonders; where morning dawns, where evening fades, you call forth songs of joy.”

And though creation struggles, God has not abandoned it. Nor has our mandate to care for it been nullified. One day, God will return to restore it to its full and perfect state. In the meantime, we are tasked to steward it in wisdom and grace.

Theology leads to behavior: bad theology results in abuse and neglect, while right theology leads to thriving and care. What we believe about our purpose as imago deis impacts the way we treat the creation that testifies to God’s glory.

Relating to one another as fellow icons

The same principle holds true in our relationships: what we believe about imago dei impacts the way we treat one another. From the beginning, God encouraged humans to partner up—“It’s not good for man to be alone” applies to humans in general, not just husbands and wives. He made the world such that we would need each other in order to accomplish our mission.

As we noted earlier, in Genesis 1:26 God commissioned man and woman to fill the earth, to rule and subdue it. It’s a big place, a challenging job, a great adventure. The first man and woman knew they could not accomplish it alone. Even after they sinned, Adam recognized Eve as the mother of all the living (Gen 3:20), a sign of hope that they would have children and that life would continue.

About that first sin. When God came looking for them (Gen 3:9), they confessed their wrongdoing. Oh, wait—never mind. With the first deflection in history, Adam pointed his finger at the woman, “The woman you put here with me, she gave me some fruit and I ate it” (3:12). Let the blame games begin. Eve blamed the serpent for deceiving her, and God explained the consequences for their actions. One of them we see in Genesis 3:16, “Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you.”

Some Christian scholars recognize this scene as the beginning of the kind of authoritarian domineering of women by men that is all too common throughout human history. The fall damaged the relationship between men and women in such a way that the physically larger and stronger commonly dominate the smaller and weaker.

Power differentials affect more than male/female relationships. Throughout history, entire people groups have lorded it over less privileged groups—the wealthy over the poor, the citizen over the immigrant. The struggles of marginalized people in all their contexts are universal. But the biblical concept of imago dei speaks to all of them.

God’s desire for marginalized people

God loves the marginalized. In his covenant with Israel, he instructed them to accept outsiders who wanted to join his people. He gave specific guidelines on how to provide for the poor and care for widows, orphans, and others without financial recourse. He described himself as “a compassionate and gracious God” (Exod 34:6). Israel, as his chosen people, was to demonstrate God’s character to the nations. They were supposed to treat the imago dei in every person with dignity.

In the following passages, I’ve italicized the significant phrase that reflects God’s heart for the lowly:

- “If an alien resides among you and wants to observe the Lord’s Passover, every male in his household must be circumcised, and then he may participate; he will become like a native of the land.” (Exod 12:48)

- “You must not oppress a resident alien; you yourselves know how it feels to be a resident alien because you were resident aliens in the land of Egypt.” (Exod 23:9–12)

- “You will regard the alien who resides with you as the native-born among you. You are to love him as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” (Lev 19:34)

- “When you gather the grapes of your vineyard, do not glean what is left. What remains will be for the resident alien, the fatherless, and the widow.” (Deut 24:21)

- “If a man encounters a young woman, a virgin who is not engaged, takes hold of her and rapes her, and they are discovered, the man who raped her is to give the young woman’s father fifty silver shekels, and she will become his wife because he violated her. He cannot divorce her as long as he lives.” (Deut 22:28–29)

Notice how God lifts up each person of lowly status. This sampling of verses reveals God’s total acceptance of outsiders who wished to join his covenant people and his desire that the needy have the means to live. Those with much were called to be generous. If pagan neighbors wanted to convert to Yahweh worship, they were welcome. If a young woman was violated, the man was compelled to provide for her for life. The powerful were to make a way for the powerless.

The imago dei was to be dignified in each person regardless of social status or life circumstance.

Jesus’ upside-down kingdom

Jesus had no time for status-seekers, power brokers, or arrogant insiders. He preached a kingdom of God populated by those who approached him like little children—humble and faithful, knowing they weren’t strong, free to love others, willing to lean on their strong Father. His ministry of preaching and healing offered hope, joy, and dignity to all he encountered. And he encountered women, Romans, the mentally and physically sick, and the immoral.

In John 4:1–42, Jesus revealed his deity for the very first time to a woman of Samaria (a despised people), engaged her in a respectful conversation that touched on her personal story, his identity, and theological truths. She and his disciples alike were shocked that he would speak with her at all. But he was only treating her how he created her, as imago dei.

In Luke 5:12–14, Jesus encountered a man with leprosy. He touched him as he healed his disease—offering dignity to a man who was considered untouchable.

In Luke 8:26–39, we read of Jesus’ mercy on the Gerasene man who had been possessed by a legion of demons. He had lived naked and fearful, in chains both literal and spiritual. At the end, he sat at Jesus’ feet, calm, in his right mind, and fully clothed—his dignity restored by the one in whose image he was made.

A short time later, Jesus encountered a woman who had been bleeding for twelve years. Beggared by ineffective doctors, exhausted and losing hope, she reached out to Jesus in faith, trusting that just a touch would heal her. It did, and he called her “daughter” (Luke 8:43–48).

When the religious leaders complained that he ate with tax collectors and sinners, Jesus responded, “It is not those who are healthy who need a doctor, but those who are sick” (Luke 5:31). Jesus’ priorities seemed upside-down to those around him, but he was showing them—and us—what right-side-up values look like. People matter because they are people.

Not because they belong to the right ethnic group or gender.

Not because they are intelligent enough, good-looking enough, or funny enough.

Not because they make all the right choices or have all the best things.

People matter because they are imago dei. Our creator declares us valuable, and his values ought to govern ours if we say we follow him.

The current kingdom outpost

If Jesus came to launch his kingdom, then he established his church to carry it forward until he returns in glory. The early church reflected his values as it became known for its humane treatment of the poor, the sick, and the unwanted. They rescued discarded babies whom Romans left out in the elements to die,6, and they refused to abandon their own sick, deformed, and imperfect children (cf. Letter to Diognetus x.i.ii).

The church became known as a religion of women and slaves—social status was laid aside as they all worshiped alongside fellow brothers and sisters in Christ. Church leadership included women deacons, abbesses, martyrs, and leaders.7

Over the centuries, organizations dedicated to mercy—such as hospitals, orphanages, humanitarian outreach—inevitably trace their roots to the church that took to heart James’s admonition:

Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world. (Jas 1:27)

But would it surprise you to know that, across generations and cultures, some who claim Christ have denied that certain people possess full status as God’s image? The evidence of this faulty understanding of imago dei ricochets through history. Anytime a Christian group or individual judges a human’s value by changeable criteria, mistreatment occurs. Women are sidelined as less valuable. A person’s race means he or she is more liable to be oppressed or rejected. Mental acuity, or the lack thereof, influences how one is accepted and promoted. Physical deformity is mocked, ignored, or feared. The wrong nationality elicits insults and hatred.

If God’s image in a person can somehow be defaced or minimized, we excuse ourselves for treating that person poorly. When we equate “true” image-bearers as those who embody particular criteria, such as high intellect and morality, or a certain gender or race, God’s definition of personhood no longer controls the narrative. We are witnesses, and sometimes culprits or victims, of such ungodly behavior today.

What makes humans valuable? We ask ourselves that question in some form every time we interact with others. Will I ignore the hurting, or make eye contact and offer to help? Will I pound the keyboard in retaliation for hurtful words on social media, or will I remember the human behind the avatar? Will I defer my “rights” so another can benefit? Will I treat people who look different than me in a way that says, “You are enough”?

Conclusion

In Matthew 25:31–40, Jesus talked of his future coming, describing a scene in which he will separate the sheep from the goats, the faithful from the unfaithful. Who enters his kingdom? Those who visited him in prison, fed him when he was hungry, gave him drink when he was thirsty, clothed his nakedness, and cared for him when he was sick. But those he invites in will protest, not remembering doing any of that for Christ. His response: “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (v. 40).

Let’s stand by our friends. Serve our neighbors. Encourage the disheartened. Support the weak, rescue the downtrodden, give to those in need.

How we treat people created as God’s image is how we treat God himself.

Related resources

- Created in God’s Image

- Being God’s Image: Why Creation Still Matters

- Identity and Idolatry: The Image of God and Its Inversion

- Donna St. George, Katherine Reynolds Lewis, and Lindsey Bever, “The Crisis in American Girlhood,” Washington Post, February 17, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/02/17/teen-girls-mental-health-crisis/.

- Carmen Imes, Being God’s Image: Why Creation Still Matters (Downer’s Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2023), 6.

- Imes, Being God’s Image, 31.

- Imes, Being God’s Image, 31.

- Michael S. Heiser, “Image of God,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, eds. John D. Barry et al. (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

- Stephanie Pappas, “Ancient Roman Infanticide Didn’t Spare Either Sex, DNA Suggests,” Live Science, January 24, 2014, https://www.livescience.com/42834-ancient-roman-infanticide.html.

- Harry O. Maier, “The Entrepreneurial Widows of 1 Timothy,” in Patterns of Women’s Leadership in Early Christianity, eds. Joan Taylor and Ilaria Ramelli (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 59–73.