The parables of Jesus are far less direct than doctrinal statements. Yet, they’re far more disruptive than simple illustrations. Parables held primacy in Jesus’s public ministry (Mark 4:2, 33–34), and they still inflame the imagination like firecrackers.

Jesus expects his parables to be understood—at least by his disciples, who have been given the secret of the kingdom of God (Mark 4:11). Parables therefore are not universal human stories. No, those who wish to be disciples of Jesus are expected to understand the parables of Jesus the way Jesus and his biographers meant them to be understood.

- What is a parable?

- What are the parables of Jesus?

- Why did Jesus speak in parables?

- Overcoming four mistakes when reading the parables of Jesus

What is a parable?

A parable, generally speaking, is a short story employed as an object lesson. (Though we’ll soon see they are also much more than that.) Parables are commonly described as “earthly stories with heavenly meanings.” Such stories are told not only for the sake of art or entertainment but always with intent to persuade.

Believe it or not, Jesus did not invent the genre of parable.

Nathan speaks a parable to David in 2 Samuel 12:1–4, Ezekiel tells a parable in Ezekiel 17:2–10, and a few more are scattered across the Old Testament. We have records of three Rabbinic parables dating from before the time of Jesus and more than fifteen hundred after him.1

A commonality between the parables of Scripture and those of the rabbis is that these stories were not mere illustrations for the sake of instructional color. While they did make teaching points more vivid, they did so by telling and retelling the story of God’s people.

In other words, Jesus and the rabbis weren’t merely grabbing serendipitous illustrations to adorn general moral or ethical teachings—the way I might search the news for sermon illustrations. Instead, they used Old Testament categories common to Israel’s shared national identity (vineyard, laborers, king and subjects, father and sons, sowing and reaping, planting and uprooting, etc.) to reshape how people perceived God’s relationship with the nation.

I have more to say on the reasons why Jesus, in particular, used parables in this way. But first, let’s clarify which teachings of Jesus qualify as parables.

What are the parables of Jesus?

While some parables are clearly labeled as “parables” (e.g., Matt 13:3), many are not. Therefore, there is some dispute as to what counts as a parable.

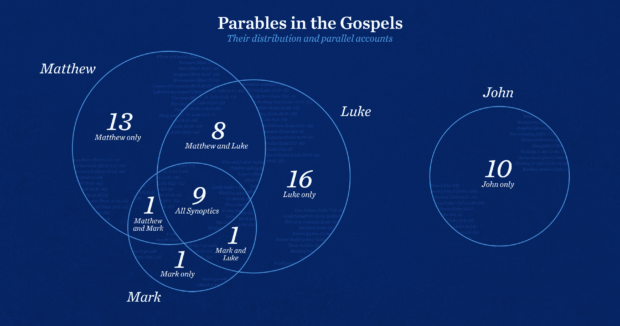

For example, the ESV Study Bible lists twenty-five parables of Jesus, while the Faithlife Study Bible lists thirty-nine and the Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels lists forty-six. All of those lists claim there are no parables in the Gospel of John, but C. H. Dodd and A. M. Hunter claim that, though the word “parable” never occurs, ten parables may still be identified in that Gospel.2

In the interest of maximum inclusion, then, here is a complete list of fifty-nine potential parables, combining data from the resources just mentioned.

Parables in all three synoptic Gospels

- Lamp under a bowl (Matt 5:15, Mark 4:21–22, Luke 8:16, 11:33)

- Wedding guests (Matt 9:15, Mark 2:19–20, Luke 5:34–35)

- Unshrunk cloth (Matt 9:16, Mark 2:21, Luke 5:36)

- New wine (Matt 9:17, Mark 2:22, Luke 5:37–39)

- Strong man bound (Matt 12:29–30, Mark 3:27, Luke 11:21–22)

- Soils (Matt 13:3–9, Mark 4:3–9, Luke 8:5–8)

- Mustard seed (Matt 13:31–32, Mark 4:30–32, Luke 13:18–19)

- Wicked tenants (Matt 21:33–39, Mark 12:1–9, Luke 20:9–16)

- Budding fig tree (Matt 24:32, Mark 13:28, Luke 21:29–30)

Parable in Matthew and Mark

- Food into the mouth (Matt 15:11, Mark 7:15)

Parables in Matthew and Luke

- Wise and foolish builders (Matt 7:24–27, Luke 6:47–49)

- Children asking father (Matt 7:9–11, Luke 11:11–13)

- Leaven (Matt 13:33, Luke 13:20–21)

- Blind leading blind (Matt 15:14, Luke 6:39)

- Lost sheep (Matt 18:12–13, Luke 15:3–7)

- Wedding feast (Matt 22:1–14, Luke 14:16–24)

- Thief in the night (Matt 24:42–44, Luke 12:39–40)

- Stewards (Matt 24:45–51, Luke 12:42–46)

Parable in Mark and Luke

- Watchful servants (Mark 13:34–36, Luke 12:35–38)

Parables in Matthew alone

- Two ways/doors (Matt 7:13–14)

- Good and bad trees (Matt 7:16–20)

- Wheat and weeds (Matt 13:24–30)

- Treasure (Matt 13:44)

- Pearl (Matt 13:45–46)

- Dragnet (Matt 13:47–48)

- Homeowner (Matt 13:52)

- Unmerciful servant (Matt 18:23–35)

- Laborers in vineyard (Matt 20:1–16)

- Two sons (Matt 21:28–32)

- Ten virgins (Matt 25:1–13)

- Talents (Matt 25:14–30)

- Sheep and goats (Matt 25:31–46)

Parable in Mark alone

- Secret growth (Mark 4:26–29)

Parables in Luke alone

- Two debtors (Luke 7:41–42)

- Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30–35)

- Friend at midnight (Luke 11:5–8)

- Rich fool (Luke 12:16–21)

- Barren fig tree (Luke 13:6–9)

- Master shutting door (Luke 13:24–27)

- Tower builder (Luke 14:28–30)

- Battling king (Luke 14:31–33)

- Lost coin (Luke 15:8–10)

- Prodigal and older son (Luke 15:11–32)

- Dishonest manager (Luke 16:1–8)

- Rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31)

- Unworthy servants (Luke 17:7–10)

- Unjust judge (Luke 18:2–5)

- Pharisee and tax collector (Luke 18:10–14)

- Minas (Luke 19:12–27)

Parables in John

- Wind blows (John 3:8)

- Bridegroom’s friend (John 3:29)

- Reaping harvest (John 4:35–36)

- Son imitating father (John 5:19–20)

- Slave not in house (John 8:35)

- Sheepfold (John 10:1–5)

- Walking in day (John 11:9–10)

- Dying wheat grain (John 12:24)

- Walking in light (John 12:35–36)

- Birthing mother (John 16:21)

Why did Jesus speak in parables?

As I mentioned above, the chief purpose of parables—whether in the Old Testament, the Rabbinic writings, or the mouth of Jesus—is persuasion. Jesus, in particular, seeks to persuade people to enter the kingdom of which he speaks.

But that doesn’t really answer the question, does it? Why parables?

In the act of persuasion, why not focus exclusively on logical argumentation, miracles, or Old Testament prophecy? Jesus uses all of those means, but what do parables contribute to the other forms of persuasion?

Jesus’s disciples ask this very question: “Why do you speak to them in parables?” (Matt 13:10). Jesus answers their question, but in a way that is sometimes wildly misunderstood. To grasp his two answers, we must grapple with the two Old Testament texts quoted by Matthew (13:10ff) and echoed by Mark (4:10ff).

Reason 1: To expose idolatry

Jesus first responds by informing the disciples that they have been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven (Matt 13:11), while those who don’t have functioning ears or eyes (Matt 13:13) have not. Such failure of the senses fulfills what Isaiah spoke about in chapter 6 of his book of prophecy (Matt 13:14–15).

This begs a serious question: Why do the senses of some (the disciples) function as they ought, while the senses of others (many in the crowds) do not?

Some might answer that Jesus himself caused this state of affairs. He spoke in parables in order to confuse people or to make them blind. Mark’s version of the dialogue might appear to support this idea, since Jesus says straight out that “for those outside everything is in parables, so that ‘they may indeed see but not perceive’” (Mark 4:11–12).

But to draw this conclusion is to misunderstand Isaiah. The book of Isaiah, including the call to ministry in chapter 6, uses sensory-malfunction language not to describe divine reprobation or foreordination to judgment but to describe the consequences of idolatry. (See Isa 42:17–20; 43:8–10; 44:9, 18–20, for some of the clearest examples.)

That terminology of seeing but not perceiving in Isaiah 6 reaches even further back into the Psalms, where those who have unseeing eyes and unhearing ears are the blind and deaf idols (Pss 115:4–8, 135:15–18). And “those who make them become like them, so do all who trust in them” (cf. Pss 115:8, 135:18).

So when God commissions Isaiah to go and preach to the people of Israel, he is not sending Isaiah to preach in order to confuse them. God sends Isaiah to preach in order to clear things up! To expose the people’s becoming as senseless as the idols they worship, so they might in fact come to their senses and begin to see and hear the truth of God.

God wants to heal and restore his people; this is why he sends them prophets (Hos 11:1–9). The problem with Israel is neither intentional hardening on God’s part nor confusing ministry on Isaiah’s part, but the people’s unwillingness to see and hear God’s compassion spoken through the prophet. (Jesus models similar compassion in Luke 13:34.)

For further study on this topic, I commend G. K. Beale’s masterpiece of biblical theology, We Become What We Worship. Regarding the passage Jesus quotes to explain his use of parables, Beale concludes:

Isaiah 6:9–10 is a just judgment from God, not a capricious happening out of the divine blue. He is punishing them by means of their own sin. It is just as in eternity, when God says to those who have rejected him and his people throughout their lives, “You did not want to spend your life in fellowship with me and my people on this earth. All right, I will give you what you wanted on this earth for eternity: separation from God and his people.” … The idols have physical eyes and ears, but they could not see or hear … And so God commands Israel through Isaiah to become like the idols, and that is their judgment … Israel will be judged by being made spiritually insensitive like the idols they worship.3

Matthew 13 and Mark 4 both quote Isaiah 6 to spotlight the fulfillment of this prophetic task in Jesus’s ministry. The context of Isaiah, with the backdrop of the Psalms, explains the “so that” in Mark 4:11–12. To paraphrase: “You have been given the secret of the kingdom, but those outside get parables, so that I may complete Isaiah’s ministry of exposing their spiritual insensitivity by handing them over to their blind and deaf idols.”

Through the parables, then, Jesus exposes the idolatry of God’s people even more fully and effectively than did the prophets of old. And that leads us to the second reason for the parables.

Reason 2: To clarify the story

The narrator of Matthew claims that Jesus’s parables fulfilled not only the ministry of Isaiah, but also the prophecy of Psalm 78.

Jesus said nothing to the crowds without a parable “to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet: ‘I will open my mouth in parables; I will utter what has been hidden since the foundation of the world’” (Matt 13:34–35, quoting Ps 78:2).

Psalm 78 recounts at length the story of the Jewish people, which the prophet wishes to be told to coming generations (Ps 78:1–4).

- According to this true story, God established the law to help them be less stubborn than their ancestors (Ps 78:5–8).

- But they constantly turned back and sinned still more (Ps 78:9-20). Though angry, God continued to show compassion (Ps 78:21–31).

- Yet they continued to sin again and again (Ps 78:32–58), to the point where God had to devastate them (Ps 78:59–66).

- Despite their sin and his judgment, he chose one tribe—one man—to shepherd them forever (Ps 78:67–72).

Just as Psalm 78 did long ago, Jesus’s parables now also clarify the story of God’s people.

It is not a story of the greatness and glory of Israel, possessors of the Law and temple, antagonists to Rome and inheritors of eternal life. It is a story of God’s compassion for a severely wayward people. A people who won’t listen. A people who won’t obey. A people who want to be like their idols. A people who need a righteous king.

While Mark doesn’t invoke Psalm 78, he makes the same point through another parable: “Is a lamp brought in to be put under a basket, or under a bed and not on a stand? For nothing is hidden except to be made manifest” (Mark 4:21–22).

According to both Matthew and Mark, Jesus spoke in parables not to confuse people but to illuminate and clarify the story of God’s covenant with Israel.

We ought not be surprised, then, that some parables provoked not confusion but unambiguous outrage (Mark 12:12).

N. T. Wright clarifies how this works:

the parables followed well-known Jewish lines. … They seem designed, within the worldview of the Jewish village population of the time, as tools to break open the prevailing worldview and replace it with one that was closely related but significantly adjusted at every point. … Jesus was articulating a new way of understanding the fulfillment of Israel’s hope.4

For this reason, claims Wright:

The parables are not simply information about the kingdom, but are part of the means of bringing it to birth. … They do not merely give people something to think about. They invite people into the new world that is being created, and warn of dire consequences if the invitation is refused. Jesus’ telling of these stories is one of the key ways in which the kingdom breaks in upon Israel, redefining itself as it does so.5

In this way, the parables are part of the very means through which Jesus brings God’s kingdom. The parables demand that hearers confess their sin, discard their idols, and pledge allegiance to the true king standing before them. Those with functioning eyes and ears will do so.

Can you see why he expected his disciples to understand the parables? Failure to understand these stories about God’s kingdom is tantamount to a failure to participate in that kingdom.

Now that we understand why Jesus spoke in parables, how do we go about understanding the parables ourselves?

4 mistakes when reading the parables of Jesus

Remembering Jesus’s two purposes for teaching in parables will help us to overcome four common mistakes.

Mistake 1: Read them as abstract, universal stories for humanity

Too often, we read the parables in a vacuum, apart from their literary context.

We read the parable of the soils, debating which and how many of the soils can be considered “true believers.” Yet the remaining parables (in Mark’s account, at least) clarify that those in the kingdom are only those who bear fruit (Mark 4:26–32).

We read the parable of the Good Samaritan and conclude that we should be kind to people. Yet this middle section of Luke speaks far more deliberately to how Jesus wants his people to go about proclaiming his kingdom.

We read the parable of the talents as though it has to do with (ahem) our talents. Yet in context, it’s about how Jesus will one day evaluate those he placed in leadership over his people. Which is, it turns out, all of us.

Solution: To read parables properly, we must give close attention to any narrative introduction or conclusion. In addition, the narrators placed the parables where they did with distinct intention. It behooves us to follow the larger argument to see how the parable advances that argument.

Mistake 2: Read multiple versions of the same parable in the same way

Just because multiple Gospels include the same parable doesn’t mean the narrators use it to make the same point.

For example, Matthew, Mark, and Luke all record the parable of the unshrunk cloth. But that doesn’t mean they are saying the same thing! Matthew and Mark focus on the damage to the old cloth. Luke focuses on the damage to the new cloth. The trick of interpretation is to figure out why.

You may have noticed on the list above that I separated the parables of the talents and the minas. Every list I reviewed puts them together, treating them as the same parable. But though they have many similarities, they also have many differences. And their different contexts strongly suggest that they are talking about different things. Different “comings” of Christ.

Solution: To read the parables properly, then, we must consider both how Jesus used the parable, and especially how the Gospel narrator used the parable. And narrators often use the same raw material for different purposes.

Mistake 3: Read them as stories for people today

We’re attracted to the parables because of their down-to-earth style and relatability (at least, once we’ve grasped such cultural artifacts as vineyards, sowing, and harvesting). We must avoid the temptation, however, to read them as though Jesus spoke them to us today.

I’ve explained above how easy it is to misunderstand Jesus’s quote of Isaiah 6 when explaining the purpose of parables. The problem is that we read the particular words in Matthew (or Mark), and we stop there. But we do not hear those words the same way a first-century Jewish audience would. That audience would hear Isaiah and understand idolatry and the Psalms.

Accordingly, the parable of the wicked tenants was not a universal story about disobedient people of all ages. Jesus’s first hearers understood clearly that the parable was “against them” (Mark 12:12). We ought to draw applications for today, but not at the expense of bypassing the intended targets of long ago.

Solution: To read parables properly, we must hear them as first-century Jews would.

Mistake 4: Read them as though there was no Bible at the time

This relates to the previous mistake, but instead of failing to perceive the cultural connections to the first century, we fail to perceive the frequent and dramatic biblical allusions.

When Jesus spoke parables of a vineyard, people would hear metaphors of the Jewish nation (Isa 5:1–7, Ps 80:8–18). When Jesus spoke parables of things lost and found, people would hear echoes of exile and return (Ps 119:176, Jer 50:6). When Jesus spoke parables of sons and fathers, people would hear references to God’s great covenant and messiah (Exod 4:22–23, Ps 2:7–9).

Solution: To read parables properly, we must read them in light of their Old Testament context.

For further study

What is it like to be a subject in God’s kingdom? The parables of Jesus set out not only to answer that question, but also to enact it.

I commend to you the many masterful parables of Jesus. Consider picking your favorite Gospel and working through each of the parables recorded there.

As you go, Logos 10 can help, especially with the Passage Guide. In the menu, click on “Guides/Workflows” and then “Passage Guide.” In the text box at the top of the Passage Guide, type the verse reference for the parable you’re studying.

The Passage Guide will then provide links to commentaries, journal articles, theology texts, and more resources that reference the parable. You’ll find particular help in the “Cultural Concepts” section to help you hear the parable the way a first-century Jew would. And the “Ancient Literature” section will survey how the earliest Christians and their Jewish contemporaries read this parable.

Just be careful to do as much work as possible in the biblical text first, before you click over to consider too many additional resources.

As you pursue your study, keep in mind the two reasons for parables and the four mistakes to avoid. By reading the parables with understanding, you will not merely be learning about God’s kingdom, but may actually be entering it.

Related resources

Fresh Eyes on Jesus’ Parables: Discovering New Insights in Familiar Passages

What Are You Waiting for? Sermons on the Parables of Jesus

Parables of Jesus: 39 Stories Told

Related articles

Parables: How They Work and Why Jesus Used Them

- Robert C. Newman, “Rabbinic Parables,” in Dictionary of New Testament Background: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 909.

- R. V. G. Tasker and I. H. Marshall, “Parable,” in New Bible Dictionary, ed. D. R. W. Wood et al. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 869.

- G. K. Beale, We Become What We Worship: A Biblical Theology of Idolatry, illustrated ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2008), 47.

- N. T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God, 5th ed. (Minneapolis, MI: Fortress Press, 1997), 175–76.

- Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God, 176.