I vividly remember the days of my youth living in Mississippi. On bright summers days, my friends and I spent a lot of time outside. We’d compare our shadows as the blazing sun hit our backs. We’d run, jump, and flail our arms, watching our shadows follow our precise movements.

As amazing as our shadows were, they weren’t the real thing. We were. The shadow only hinted at the reality of who we were—in shape, size, and essence. In this way, our shadows served as a “type” or representation that depicted the actual person.

Biblical typology is much like that childhood game of observing our shadows. As Paul explains in Colossians 2:16–17,

Therefore let no one pass judgment on you in questions of food and drink, or with regard to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath. These are a shadow of the things to come, but the substance belongs to Christ.1

Typology reveals the continuity and depth of God’s redemptive plan between the Old and New Testaments. In 40 Questions about Typology and Allegory, Mitchell Chase explains,

a biblical type is a person, office, place, institution, event, or thing in salvation history that anticipates, shares correspondences with, escalates toward, and resolves in its antitype.2

The connectedness between the Old and New Testaments supports our understanding of how earlier figures and stories in the Bible are not only historical accounts but also foretastes of the salvation that Jesus Christ, the Messiah, ultimately brings. This approach deepens our knowledge of the Bible and serves as a pathway toward viewing Scripture rightly as one unified narrative of redemption for God’s people.

In this article, we explore how specific Old Testament figures and events—like Adam and Eve, Noah and the flood, and Abraham—serve as typological foretastes of the Messiah and his salvific work. Like a game of observing shadows, examining the events and the lives of those who foreshadowed the Messiah helps us better gaze upon the actual person and work of Christ.

Adam and Eve, Christ and the church

In Genesis we come to know the first man and woman to be Adam and Eve. Not only do the pair mark the beginning of humanity’s existence, but they provide types of what Christ accomplishes.

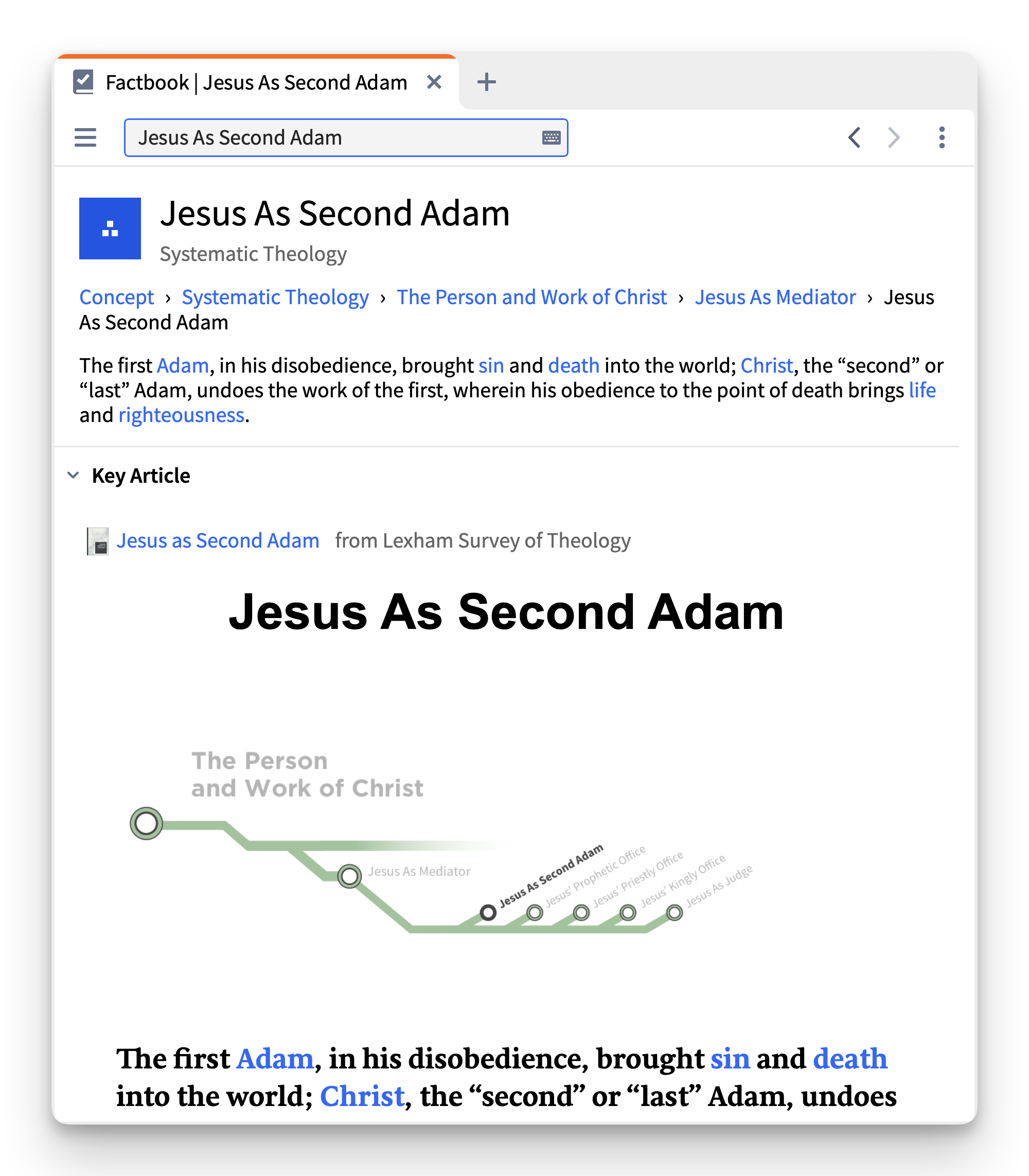

First, in Romans 5:14, Paul speaks of Adam as one “who was a type of the one who was to come.” Adam represents humanity. As such, he functions as a type of “the one who was to come,” pointing to the Messiah, Jesus Christ, the redeemer of all humanity. Whereas Adam is the first in the existence of humanity, Jesus is the culmination in the redemption of humanity. Adam’s failure marks the beginning of sin’s reign over humanity, but Christ’s perfect obedience and death on the cross marks the end of sin’s dominion over humanity (Rom 5:15–19; cf. 1 Cor 15:21–22, 45–49). The first Adam forms a shadow of the last Adam. Every element of failure in the first Adam is overshadowed by the triumphs of the final and better Adam, Jesus Christ.

Launch your own study of Jesus’s role as the second Adam using Logos’s Factbook tool. Get it free, if you don’t already have it.

Second, in Genesis 2:21–23, God creates Eve from the rib of Adam. Specifically, Eve is created to be a “helper” for him (Gen 2:20). God calls Eve to come alongside Adam in his mission of ruling and subduing the land and animals (Gen 1:26–28). Adam and Eve’s union serves as a typological foretaste of the relationship between Christ and the church (Eph 5:31–32).

In 2 Corinthians 11:2, Paul speaks of the church as being “betrothed” to Christ. Eve was the first bride; the church is the eschatological bride (Rev 21:1–3). As Eve is made alive through Adam’s body (Gen 2:21–23), so is the church called to new life through Christ’s sacrifice by dying on the cross (Eph 5:25–30). As Eve was given to complement Adam and come alongside him in fulfilling the purposes of God (Gen 1:26–28), so is the church given to Christ, the last Adam, to participate his purposes by carrying out his mission on earth (Matt 28:18–20).

Noah and the flood, Christ and baptism

We are introduced to Noah in Genesis 5:29–29. Like Adam, Noah is also seen as a type of Christ (Gen 9:1–7).3 Noah stood as a righteous figure during a time when corruption and wickedness among humanity were widespread (Gen 6:9–11). Noah was chosen by God to preserve humanity and the animals; so too Christ was chosen to be a sacrifice and bring salvation to those who believe upon him (1 Pet 1:18–21). Noah’s obedience to God in building the ark foreshadowed Jesus Christ’s obedience to God the Father in both life and death (Phil 2:8).

The flood is also a typological event representing baptism (1 Pet 3:21). The flood washed away everything that was outside of the ark (Gen 7:21–23). Noah, his family, and the animals selected to be on the ark mark the beginning of a new life for humanity (Gen 8:1).4 The flood symbolizes baptism because, just as baptism represents a passing through judgment and the beginning of life free from the bondage of sin (Rom 6:1–11), so too the flood was a judgment that brought about a new beginning for humanity.

Abraham and the covenant, Christ and the new covenant

Believers know Abraham as the father of faith, whose belief in God’s promise is credited to him as righteousness (Gen 15:6). Abraham’s life prefigures the Messiah in several insightful ways.

First, in Genesis 12:1 God invites Abraham to trust him by calling him to leave his native place and travel to an unknown land. In return, God promises Abraham that he will “make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing” (Gen 12:2). Abraham’s obedience in trusting God and following his command mirrors the obedience of Christ. God the Father calls his Son, Jesus Christ, to obediently follow his will, and Christ does so even to the point of dying on the cross (Phil 2:8). In Matthew 20:28, Jesus says, “even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

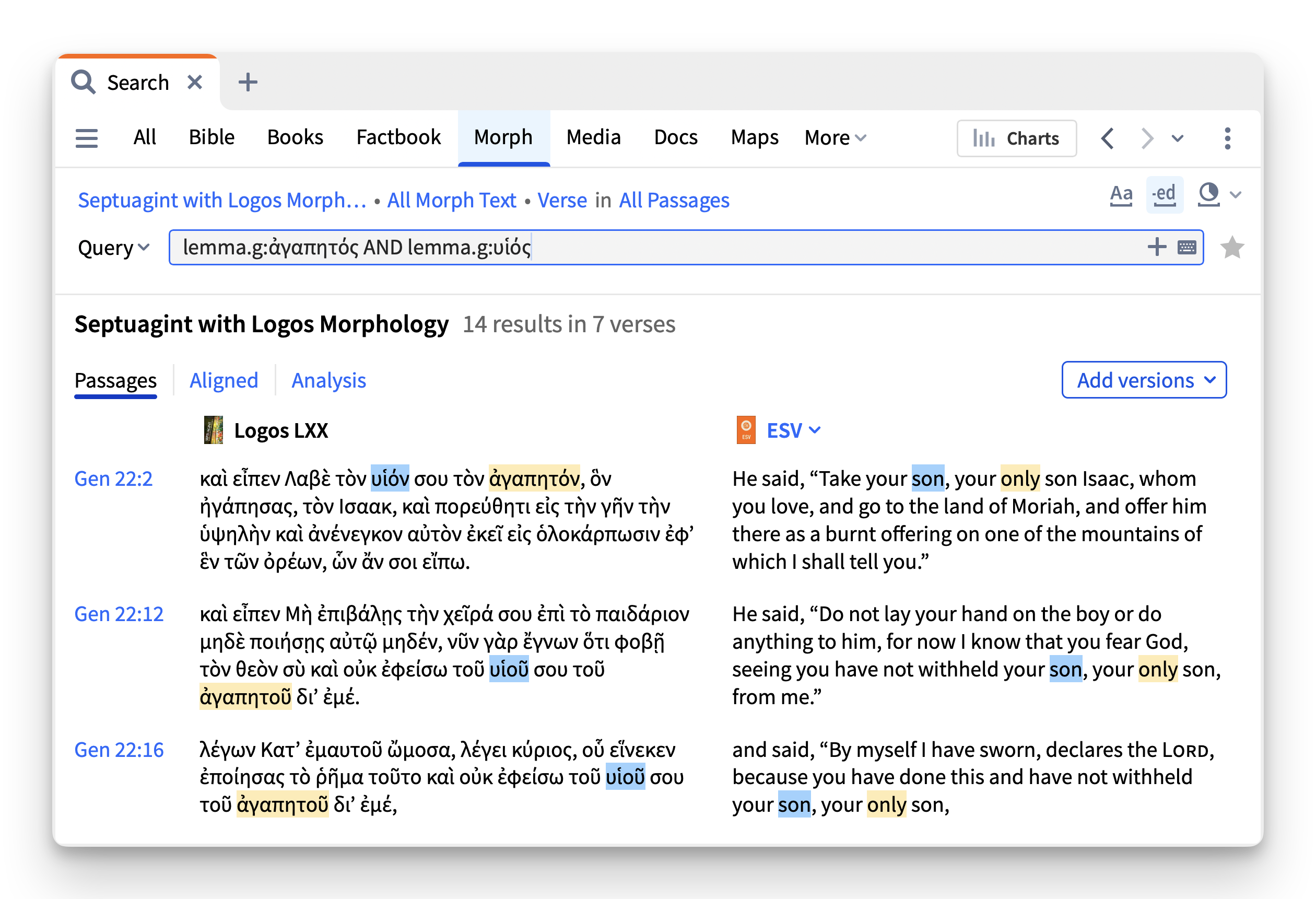

Additionally, Abraham’s role as a father also foreshadows God as the Father of Jesus Christ. In Genesis 22, God tests Abraham’s faith by directing him to offer his son, Isaac, as a sacrifice. While Isaac was not Abraham’s only son, he was the promised son through whom God had declared to bless Abraham and make him a great nation (Gen 17:19–21). Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, Isaac, is a foretaste of God the Father’s willingness to offer up his own son, Jesus Christ. In both instances, Isaac and Jesus, are described as “beloved sons”5 and are to be offered up as sacrifices according to the will of God. At just the right moment, God spares Isaac and provides a substitutionary sacrifice of a ram in the bush (Gen 22:11–13). This substitution in the account of Isaac foreshadows the substitutionary atonement that believers received through Christ Jesus (1 Pet 3:18).

Use the Search tool in Logos to look up this combination of words across the Bible. Get the Logos app free, if you don’t already have it.

Finally, Abraham’s life helps us understand the nature of the covenants God makes with his people. In Genesis 15, we are presented with God’s covenant with Abraham. Under this covenant, God promises that Abraham and Sarah will have many descendants who will inherit the land of Canaan. These covenant promises foreshadow the new covenant that is realized and perfected through Christ. God’s promises to Abraham are ultimately fulfilled in Christ, as underscored by Paul in Galatians,

Know then that it is those of faith who are the sons of Abraham. And the Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “In you shall all the nations be blessed.” So then, those who are of faith are blessed along with Abraham, the man of faith. (Gal 3:7–9)

The promise that Abraham would be a blessing to all nations (Gen 12:2–3) is ultimately fulfilled through the Jesus Christ, Abraham’s true seed, who opens the way for all people to join the family of God (Gal 3:14, 27–29; 4:28).

The value of biblical typology

Like observing our shadows, we can enjoy and appreciate the depths of Scripture by exploring typology. While some might be inclined to think of typology as a mere academic interest, God gave us biblical types in order to deepen our understanding of him and his plan of salvation. Through the types of Adam and Eve, Noah and the flood, and Abraham and the covenant, we meet not only historical figures but real people and events that played pivotal roles in carrying out God’s redemptive mission.

One of the greatest benefit to studying biblical typologies is the ability to see the Bible as one unified story. Types provide clarity for understanding Scripture’s overarching narrative. This deeper insight into the Bible enriches our growth in the grace and in the knowledge of Christ (2 Pet 3:18) by allowing us to more fully behold his majesty (2 Cor 3:18).

Continue your study of typology in the Old Testament with these suggested resources

Typology: Understanding the Bible’s Promise-Shaped Patterns; How Old Testament Expectations are Fulfilled in Christ

Regular price: $39.99

Biblical Typology: How the Old Testament Points to Christ, His Church, and the Consummation

Regular price: $19.99

Five Views of Christ in the Old Testament: Genre, Authorial Intent, and the Nature of Scripture (Counterpoints)

Regular price: $20.99

Preaching Christ from the Old Testament: A Contemporary Hermeneutical Method

Regular price: $25.99

The Unfolding Mystery, 25th Anniversary Edition: Discovering Christ in the Old Testament

Regular price: $12.99

Related articles

- What’s Typology? Patterns of Creation in Redemptive History

- Parousia: What the New Testament Says about the Second Coming

- Typology’s Logic: Chekov’s Gun & Bible Interpretation

- Finding Jesus Where He Isn’t: 2 Rules for Typology

- Emphasis added. All Bible quotations are taken from the ESV.

- Mitchell L. Chase, 40 Questions about Typology and Allegory, ed. Benjamin L. Merkle, 40 Questions Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic, 2020), 38.

- Notice how Genesis 9:1–7 repeats the language “God blessed” (9:1), “be fruitful and multiple and fill the earth” (9:1, 7), dominion over the animals (9:2–3), and humanity as made in God’s image (9:6), drawing clear parallels with Adam in Genesis 1:26–30.

- As the The ESV Study Bible notes, the Hebrew word translated “wind” in Genesis 8:1 is the same word used elsewhere for “Spirit” (e.g., Gen 1:1). Thus, Genesis 8:1 casts the subsiding flood as something of a new creation, intentionally echoing Genesis 1:2 where the Spirit likewise hovered over the waters of an unformed creation. T. Desmond Alexander, “Genesis,” in ESV Study Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008), 64.

- The Greek phrase used to described Jesus as God the Father’s “beloved Son” (e.g., Matt 3:17) is the same phrase used in the Greek Old Testament (LXX) to designate Isaac as Abraham’s “beloved son” (e.g., Gen 22:2 LXX).