What’s your background (academic and otherwise) and how did that prepare you to write Paul and the Image of God?

I grew up in a small, charming town in Tennessee, USA, where I fell in love with Bible and Theology during my undergrad (a BA in Religious Studies) at Lee University. From there, my wife and I hopped around a bit–from Tennessee to St Andrews for an MLitt in Bible, to Duke Divinity School for a ThM in New Testament, and then back to St Andrews for a PhD in New Testament with Tom Wright.

In this connection, what most prepared me to write Paul and the Image of God was simply my long-standing fascination with Paul. I had familiarized myself with most of the major players and debates from, say, Sanders’s 1977 Paul and Palestinian Judaism to Wright’s 2013 Paul and the Faithfulness of God. Obviously, I had loads to learn, but, as far as studying Paul goes (at least in the English language!), I felt reasonably prepared.

What is the central argument of your book?

The book’s central argument is that Paul’s ‘image christology’ is not strictly speaking an Adam christology but a wisdom christology in which Paul appropriates elements of Jewish sophia speculation and Middle Platonic intermediary doctrine so as to include the preexistent Jesus within his monotheistic doctrine of creation and yet to distinguish him from God the father, as the latter’s unique cosmogonical image.

What is the main takeaway for the academy from your book, and what new questions has it raised for the study of Paul and the imago dei?

Paul’s image christology is a divine christology in which the preexistent Jesus is included within the most exclusive theological-conceptual category of second temple Jewish monotheism: cosmogonical activity. And this image christology reflects the appropriation not just of the Jewish wisdom tradition but of elements of Middle Platonic intermediary doctrine.

In this connection, however, there are questions that I did not get fully to engage.

- Why did Paul and other early Jewish Christians feel the need to ascribe preexistence and then cosmogonical activity to (the preexistent) Jesus? What texts/traditions might have resourced them in doing so?

- What is the relationship between Paul’s christology and theological anthropology, particularly as this is expressed in his image and Adam christology?

- How much and in what ways was Paul influenced by the philosophical tradition?

- Is the “fall into Hellenism/philosophy” narrative that characterizes so many accounts of the development of christology justified?

What benefit does your study bring to the church?

Perhaps above all, the study shows, I hope, that the movement from Jewish monotheism to Chalcedonian christology, from the Old Testament to the Patristic period, from Paul’s christology to an explicit two-natures christology is not as inorganic as is sometimes made out.

Discuss your experience working with N.T. Wright. How did his supervision contribute to your project, and also your growth as a scholar and person?

It’s hard to quantify Professor Wright’s influence on me and on the project. His entire way of doing history, biblical studies, and theology runs thick in my blood. He is, of course, brilliant. But he was also present, attentive, curious, supportive, and above all excited and willing to question some of his own views.

How has Paul and the Image of God factored into your current and future research plans?

I’m currently working on a manuscript on the relationship between Paul’s christology and his theology of Torah (The Torah’s Telos: Christ and the Law in Pauline Theology) and I look ahead (perhaps in foolhardiness) to the possibility of doing something like Larry Hurtato’s Lord Jesus Christ. We will see.

But I remain fascinated by the whole constellation of questions to do with the movement from Jewish monotheism to Chalcedonian christology.

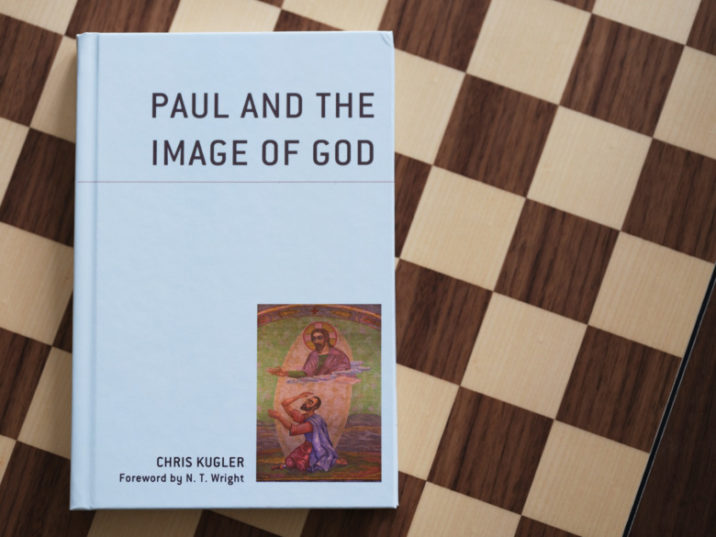

Get your own copy of Kugler’s Paul and the Image of God here: