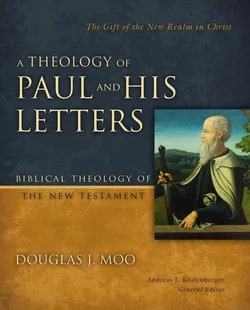

Douglas Moo writes, “The apostle Paul has arguably had a greater impact than any figure other than Jesus Christ Himself.”

Moo, a New Testament scholar and professor at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, has spent more than 30 years in intense study of Paul—what he says has been primarily reading, rereading, and rereading Paul’s letters. (He’s published several theological works and commentaries on the Bible—notably, An Introduction to the New Testament and The Epistle to the Romans.)

And now the fruit of his study of Paul is compiled into one volume, The Theology of Paul and His Letters. It’s a gem 15 years in the making—a “daunting task,” writes Moo, but one that brings all his years of experience studying, teaching, and writing about Paul into one comprehensive guide that will serve readers as a go-to resource for decades to come.

In this excerpt from A Theology of Paul and His Letters, Moo answers the question: What Is Pauline Theology? to help explain his approach to not only studying the rich deposit Paul left us—but also writing the book.

***

A question that continuously surfaced in a years-long discussion of Pauline theology at the annual Society of Biblical Literature meetings was a deceptively simple one: Where do we find Paul’s theology? Specifically, do we find his theology in his letters or behind his letters? Should “Pauline theology” be a summary of what he says in his letters? Or should Pauline theology be a reconstruction of Paul’s thought that we can discern behind his letters?

. . . I answer yes. We have no access to Paul’s thought outside the letters he wrote, preserved for us in Scripture. But Pauline theology must be more than a simple repetition of what we find on the surface of Paul’s letters—otherwise, it would be hard to distinguish theology from exegesis. The Pauline theologian must penetrate “behind” the text in an effort to uncover the basic framework and content of Paul’s thinking. Jouette Bassler summarizes the process and the desired theological outcome

The raw material of Paul’s theology (the kerygmatic story, scripture, traditions, etc.) passed through the lens of Paul’s experience (his common Christian experience as well as his unique experience as one “set apart by God for the gospel”) and generated a coherent (and characteristic) set of convictions. These convictions, then, were refracted through a prism, Paul’s perception of the situations that were obtained in various communities, where they were resolved into specific words on target for those communities.1

In a sense, this is simply the move from exegesis—describing what is in the text—to theology—synthesizing what is in the text. This is what “Pauline theology” is.

The minute we make this move “behind” or “beyond” the text, however, we inevitably introduce a strong measure of subjectivity. This is most obvious among scholars who self-consciously choose a perspective from our own context to use in interpreting Paul: for example, feminism,2 postcolonialism,3 or “post-Holocaust hermeneutics.”4

I acknowledge that the interpreter of Paul will inevitably bring some of their own “baggage” into their interpretation. Nor is that baggage always a problem. For instance, Lisa M. Bowens has documented how black interpreters of Paul in North America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries “resisted” a certain biased perspective on Paul as endorsing slavery.5 The experience and social position of these interpreters brought valid and important corrections to a certain dominant view of Paul.

My own experience of teaching Paul in various parts of the world has shown again and again how perspectives from different geographic, social, and cultural contexts can shed light on texts—light that my limited perspective might not have seen so clearly. To use the terms often heard in this discussion, our task is not to “resist” the text—quite the contrary, I am called to submit to the text. But I am called to resist distortions of the text or imbalances in our synthesis that have crept into our theology. And listening to voices from different eras of the Church and from different parts of the contemporary Church helps to identify where this kind of “resistance” is needed.

I am a North American, white evangelical whose thinking has been strongly influenced by Reformation theology. Biases stemming from my identity are undoubtedly present in this volume. But, through sympathetic listening to the voices of others, both ancient and modern, and—not least!—the ministry of God’s Spirit as I read and reread Paul, I am also hopeful, if not confident, that what I claim to find in the text really is in the text.

***

Join Douglas Moo in this engaging, insightful, wise, substantive, and evangelical treatment of Pauline theology in The Theology of Paul and His Letters.

Related articles

- Transform Your View on Pauline Theology

- 3 Debates about Paul’s Theology You Might Not Know Exist

- Paul and the Law: 3 Texts that ‘Set the Record Straight’

- Paul’s View of the Law: A Freedom from (or End to) Jewish Law?

- Jouette M. Bassler, “Paul’s Theology: Whence and Whither?,” in Pauline Theology, Volume 2: 1 and 2 Corinthians, ed. David M. Hay (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1993), 11.

- E.g., Cynthia Briggs Kittredge, “Feminist Approaches: Rethinking History and Resisting Ideologies,” in Studying Paul’s Letters: Contemporary Perspectives and Methods, ed. Joseph A. Mar- chal (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2012), 117–33; Sandra Hack Polaski, A Feminist Introduction to Paul (St. Louis: Chalice, 2005).

- Davina Casperina Lopez, Apostle to the Conquered: Reimagining Paul’s Mission (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2008).

- See, e.g., Angus Paddison, Theological Hermeneutics and 1 Thessalonians, SNTSMS 133 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univer- sity Press, 2005).

- M. Bowens, African American Readings of Paul: Reception, Resistance, and Transformation (Grand Rapids: Eerd- mans, 2020); see, for a broader hermeneutical perspective, Esau McCaulley, Reading While Black: African American Biblical Inter- pretation as an Exercise in Hope (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2020).