This excerpt featuring pastor and author Philip Yancey is adapted from the free guide How to Study the Bible, originally published in the Nov.–Dec. 2014 issue of Bible Study Magazine. It is presented as originally published.

In this guide, 12 trusted Christian teachers reveal how they approach their own Bible study.

Philip Yancey: Finding Grace in the Borderlands

Writer and speaker Philip Yancey grew up thinking his church was a safe place.

His family was deeply involved in the community. And he was saturated with Scripture, memorizing Old Testament stories, and attending Sunday school and church camps. But as a young adult, he began to see the signs of an insular and unhealthy church life. “The attitude was one of keeping away from sinners to avoid being polluted by them. It was a very defensive mentality.”

Yancey’s crisis point came over the issue of racism. In the early days of the Civil Rights era, Yancey’s church cited the Bible as proof of inferior races. But his time working under an African-American professor brought the church’s teaching into stark contrast with reality. “I had been taught that people of color are good at working in restaurants or fixing cars, but could never be a CEO of a company or a college professor. I mean, this is in our lifetime and I was taught that.” The experience brought on a crisis of faith. He recalls thinking, “My church was wrong. What else were they wrong about?”

However, Yancey found that his early exposure to the Bible brought him back to faith. “The Bible corrected what I had picked up in that unsafe church. As I began to study Jesus, I realized that he didn’t have that insular approach at all. He was accused of hanging around sinners all the time. It seems like the least likely people were most attracted to Jesus, but the uptight religious people were threatened by him.” This realization was liberating for Yancey, who began to see a biblical calling to “extend the grace and the good news that we have encountered, and to express it in a way people can relate to—in a way that answers their own needs.”

Early Career—Faith and Scripture

Today, Yancey likens himself to a pilgrim exploring God and the Bible, and he takes readers with him in his search for answers. His own journey back to faith was fostered by key mentors while working as a journalist at Campus Life magazine. “The atmosphere was very nourishing. We were trying our wings as writers, and my editor, Harold Myra—later the publisher for Christianity Today Incorporated—was a very wise mentor to me.”

It wasn’t until he wrote Disappointment with God that Yancey had his first deep encounter with Scripture. The book explores Scripture to find why God sometimes acts in the world and sometimes seems silent. “I was aware that God acts in a very direct, dramatic way in the Bible. And there are other times when God seems almost silent. I was reading in Exodus about how the cries of the Israelite slaves in Egypt reached the heavens. God decided to act, but before that, he had been silent for over 400 years. I decided to go through the Bible and look for every time God acted and see what those events had in common. I holed up for two weeks in a mountain cabin. The only book I read was the Bible. I went all the way through, noticing and taking notes on every time God intervened.”

Not long after that, Yancey was hired to write notes and material for the NIV Student Bible. For three years, he went through every chapter of the Bible. “I read these books several times all the way through, before even thinking about what to say and then went to the commentaries. That project set the tone for my understanding of Scripture, and also set the course for later writing topics.”

Living in the Borderlands

When it comes to choosing his subjects, Yancey writes about issues that affect people living in what he calls “the borderlands.” Generally, his work appeals either to those who have little direct experience with Christianity and are curious but cautious or to believers like him, who have been hurt by the church in the past. “Both groups come to the borderlands from different directions. I went through a period of time where I—like the agnostics—tossed it all aside and said, ‘I just don’t believe it; these people are crazy.’ I have a great empathy for people in that situation. And because I can identify with their state of mind, I ask myself how I can present what I believe in a healthy way.”

In 1977 Yancey published Where Is God When It Hurts?—a book prompted by years of hearing hurting people tell him that their pain was made worse by other Christians. Yancey heard from people who were going through severe illness and had been told they were being punished by God, persecuted by the devil, or set up as an example of suffering. Instead of bringing further confusion and more pain, Yancey thought, “‘We should be able to bring comfort at a time like that.’ This book was my attempt to find the answer to that question.”

Yancey found that the conclusions he presented prompted even more questions from readers. “I heard from all sorts of other people who said, ‘That’s not quite my situation. I deal with depression,’ or ‘I have a child with a congenital defect,’ or ‘My problem is I’m disappointed in God. I’m disappointed with life.’ Over time, I continued to be asked to speak to the question, ‘Where is God when it hurts?’ I’ve spoken at Virginia Tech; Newtown, Connecticut; Japan after its 2011 earthquake; and Bombay in the wake of the bombings. I’ve been in front of people who were going through great grief and asked to try to help them find some perspective and comfort. Years ago, when I first jumped into the topic, I was just trying to figure it out for myself. It wouldn’t have been my choice as a 20-something. But it has sort of become the theme that never goes away.”

“Sometimes people who were raised in healthy families and churches read my books and don’t understand why I struggle. When I wrote Disappointment with God, my publisher was nervous about that title. When you go into a Christian bookstore, you see books like The Christian Secret to a Happy Life. But I hear from people who are disappointed, and I want to speak to them. I feel blessed that I can spend time wrestling with these issues. I go to people who can help me and try to come up with something to help others.”

Seeing God through Jesus

Yancey finds that it’s difficult for people to put together a belief in a loving God when terrible things have happened. “One of the most important things I’ve learned is [to] make your decisions about what God is like through Jesus. Michael Ramsey, the Archbishop of Canterbury, said, ‘In God, there’s no un-Christ-likeness at all.’ So when I want to approach a new topic like prayer or an old topic like suffering, the first thing I do now is go to Jesus. If you want to know how God feels about people who are going through hard times, look at how Jesus responded to the widow who just lost her son, or the Roman soldier with the sick servant. That’s how God feels toward us.”

“A lot of people get hung up on whether God likes them or is punishing them. But look at Jesus—he never said anything like that. That applies generally to Bible study as well. The purpose of the Bible is to communicate Jesus. The Old Testament anticipates him all the way through. The Gospels and the rest of the New Testament reflect the life of Jesus, what it means for us, and what it means for the world.”

Personal Bible Study

When it comes to his personal study, Yancey finds the simplest routine is the easiest to maintain. He reads, meditates, and prays through one chapter of the Bible per day. “I just focus on seeing what speaks to me, and what I need to learn from and be challenged from that day.” Yancey also recommends reading the individual New Testament letters in one sitting, “as they would have been by the first people who heard them. Various programs give you plans to read the entire Bible or the New Testament in 40 days, and I’ve done those things before, as well. But honestly, my daily reading is usually just one chapter at a time.”

Yancey says he is much more comfortable with mystery in the Bible than he used to be. “In my youth, I wanted to nail down everything. I wanted it to be clear. It used to frustrate me when Psalm 22, for example, cries out, ‘My God, why have you forsaken me?’ This is the passage Jesus quotes from the cross. But in the next psalm we read, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want.’”

Today, rather than seeing those differences as contradictory, Yancey recognizes that the Bible addresses “all of human experience. There are some days I can’t relate to Psalm 22 at all. There are some I can’t relate to Psalm 23 at all. But I know that there are times when I need each one of those. Ecclesiastes and the Song of Solomon are so different. One celebrates the joy of life and love and sexuality, and the other one is the despair of the old, tired, wealthy person who has tried it all and says, ‘Is that all there is?’ I’ve experienced both of those. And I’m much more comfortable with the variety of the Bible now than when I was young.”

The Bible and Imagination

Yancey encourages others to engage their imaginations when reading the Bible. “The deadening part of Bible study is when you think you’ve already got it all figured out. It’s easy to fall into the trap of feeling like you’ve heard everything before and that you have nothing left to learn. We should do whatever we can to cut through the scum that has grown on our understanding and rediscover freshness.”

Yancey experimented with imaginative approaches to Bible study in a “Walk through the Bible” class he taught years ago. “We spent five years getting through the Old Testament, so when we started on the Gospels, my students and I both needed something new.”

Yancey borrowed a comprehensive collection of movies on Jesus, and passage by passage, he cued up clips of related scenes. “They spanned the spectrum, all the way from clips of the Campus Crusade’s ‘The Jesus Film,’ old silent movies, and modern versions, like ‘The Last Temptation of Christ.’ We would watch about four different clips of the same scene. Every approach to a scene is so different—for instance, the scene of the woman caught in adultery in John 8. One of them made the woman look really bad. Another presented her as a victim for whom you should feel compassion. The depictions of Jesus were also very different. Some were bland and one-dimensional, and others were very passionate.”

For Yancey and his students, the film clips provided a comparison of views, and paying attention to a filmmaker’s preconceptions about Scripture helped expose and strip away their own. “As a group we’d go back to Scripture to see what really happened. It was a great, creative way of starting afresh and seeing a scene the way we hadn’t seen it before.”

Yancey and his class used the film collection to work through the Gospels for two years, and the experience was the genesis for his book The Jesus I Never Knew. And while the film approach may not work for everyone, Yancey’s advice is to “use what sparks imagination. Henri Nouwen wrote this book, The Return of the Prodigal Son, where he walks readers through the story, picturing themselves in turn as the father, the younger brother, and the older brother. The story itself was certainly radical in Jesus’ day. People could never predict what he was going to say or do. The more we can resurrect that unpredictability when it comes to our interactions with Scripture, the closer we are to what happened in Jesus’ day.”

Start by Doing

Yancey’s latest book, Vanishing Grace, is a reflection on the largely negative perception of Christians in Western culture. In it, Yancey meditates on the church’s high purpose of “dispensing God’s grace to a thirsty world” and questions why the body of Christ seems more infamous for political activity than famous for grace. Western society has moved into a post-Christian state, and it is no longer normal or assumed that the people around you have an active church life. “In some ways, I think this can be a good opportunity.”

The first-century Church flourished as a religious minority for hundreds of years. “All of the images of Jesus and of the kingdom are small things: be a light in the darkness. Be salt, and a little bit of salt keeps the whole society from going rancid. This experience isn’t new to Christianity. The exception is what took place, on the surface at least, in the United States 50 years ago. People want to go back to those old days, but it’s probably not going to happen. Instead, we should be asking: How do we respond to a post-Christian society?”

Yancey asked himself whether the good news of the gospel is still, in fact, good news to people who hear it. He found that humans are as aware as ever of their need for a savior, but that perhaps the style of communication needs to change. “It’s time to start by doing rather than talking. Reach out in works of mercy and serve people. That touches people’s hearts, and then they want to know why you do these things. I’ve seen this all over the world.”

***

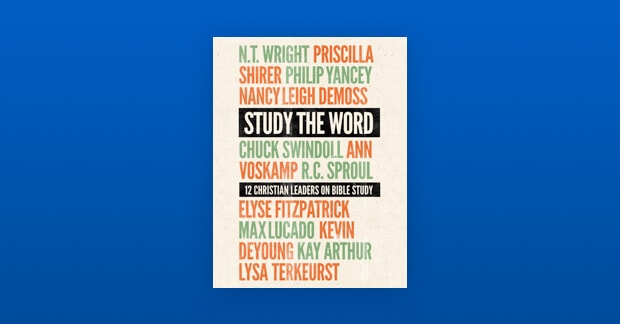

Read more encouraging testimonies from influential Christian leaders like Nancy Leigh DeMoss, R.C. Sproul, and Priscilla Shirer. Download your free ebook How to Study the Bible today.