How would you find all the rhetorical questions in the New Testament—like “What sort of man is this, that even winds and sea obey him?”

Finding such questions—questions which aren’t seeking answers but are instead making statements—is a tougher task than it may first appear. As far as I know, Logos 7 is the only tool that can do it.

Sentence Types

Every kid in school is taught the three sentence types:

- Declarative sentences make assertions, such as, “God so loved the world, that he gave his only son.”

- Interrogative sentences ask questions, such as, “Who do men say that I am?”

- Imperative sentences give commands, such as, “Let your light shine before others.” (Sometimes “exclamatory” sentences are added to the list, those which state something emphatically, but we’ll subsume those under declarative).

Logos 7 includes the “Sentence Types” dataset dividing New Testament clauses into these three categories.

But if you want to find a rhetorical question in Scripture, you can’t just search for question marks—because not all interrogatives are rhetorical. There is nothing grammatical that sets a rhetorical question apart from other questions. The tense of the verb, the order of the words in the sentence—it all looks just the same as an information-seeking question. We know a rhetorical question when we see one only because we humans are experts at discerning meaning.

Speech Acts

That’s why Logos 7 also includes the Speech Acts dataset. It describes sentences in the New Testament according to the apparent purpose of those who uttered or wrote them.

Speech Acts (in the schema adopted by this dataset) also divide into three categories: “informative” speech acts, which deliver (or request) information; “obligative” speech acts, which direct someone to do something or promise that the speaker will do something; or “constitutive” speech acts, which either state something about the speaker’s internal state or, if the speaker has the requisite authority, effect change in the real world (the classic example is, “I now pronounce you husband and wife”—which only works if you’re the right person in the right setting).

If you made it through that paragraph, I’m giving you five extra points. Now let’s get to the good stuff: examples. Here are two passages illuminated by the Speech Acts dataset. The first two are rhetorical questions.

1. “Who is it that struck you?”

You know intuitively that not all interrogatives are uttered for the purpose of seeking information. For example, take the mocking “question” of the men slapping Jesus as he stood before the chief priests the night prior to his crucifixion:

Then they spit in his face and struck him. And some slapped him, saying, “Prophesy to us, you Christ! Who is it that struck you?” (Matt. 26:67–68).

This is a kind of rhetorical question, one in which the individual speaking is expressing something about himself, namely his cruelty and mockery. The Sentence Types dataset faithfully and rightly marks that last sentence as an interrogative. But the Speech Acts dataset marks it as a “Constitutive-Expressive” speech act. That language is doing something, it’s expressing the speaker’s inner state.

2. “Which one of you, when his son asks for a fish, will give him a stone?”

There’s another kind of rhetorical question, one which states something as fact:

“Which one of you, if his son asks him for bread, will give him a stone?” (Matt. 7:9)

This is a rhetorical question, because Jesus wasn’t expecting anyone to raise his hand say, “Uh, me—yeah, I’ve done that. . .” Jesus was doing what good teachers do; he was using an interrogative sentence type to state a fact dramatically, namely, “nobody does this.”

More power

Anybody with basic language-processing capability can tell what the two passages above mean. You don’t need two wonky datasets to help you. So why bother with them?

Because: only by combining the power of the datasets like the Speech Acts and Sentence Types datasets can we search for both form (which tell us what kind of sentence we’re reading) and meaning (which tells us why that sentence is there). Only with these two datasets can you find rhetorical questions.

And not just rhetorical questions—these two datasets can find other interesting things, such as declarative sentences which are doing something more subtle than relaying information.

“Lord, my servant is lying paralyzed at home, suffering terribly” (Matt. 8:6) is marked as a declarative sentence type, but as an “obligative-directive” speech act. On the level of form, the centurion is stating something; on the level of meaning, he’s trying to get Jesus to do something for him.

Again, you know this intuitively when you read it, but can you find other examples?

The How-To

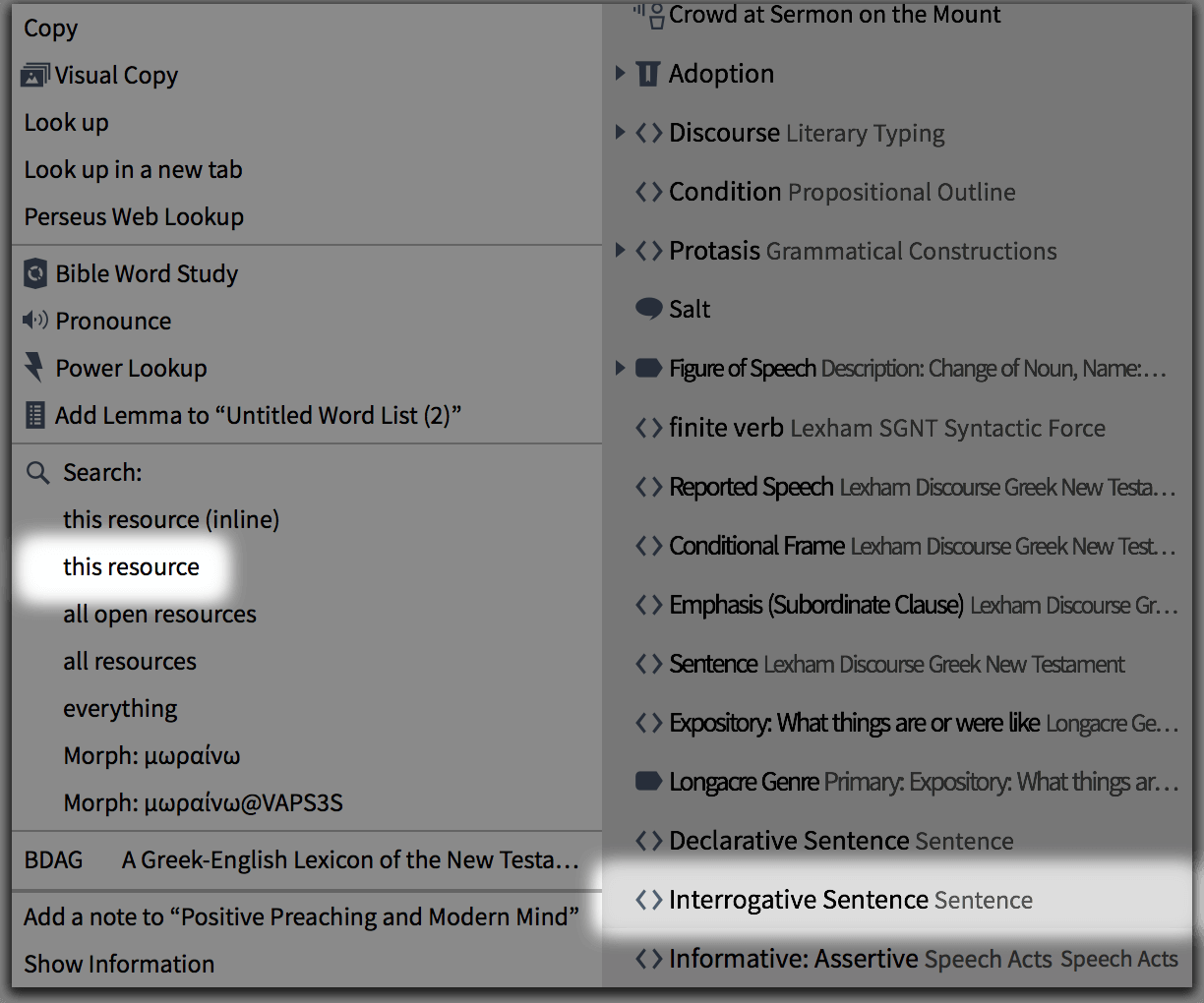

To find out how a given clause is marked, just right click on it and look at the bottom right of the context menu that comes up. Let’s try this on the rhetorical question in Matt. 5:13:

If salt has lost its taste, how shall its saltiness be restored?

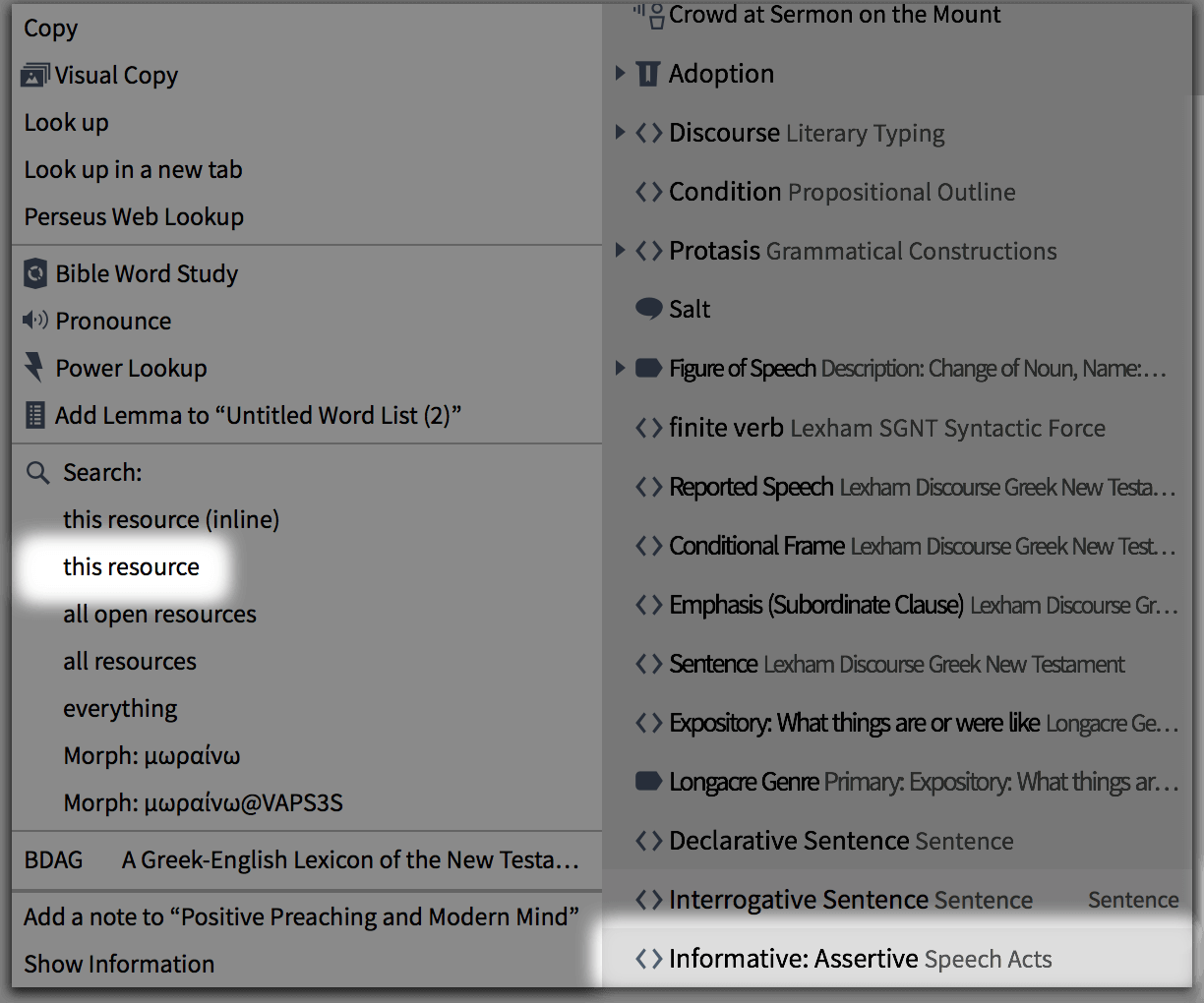

After you right click, click the sentence type in the context menu, then select “search this resource” on the left to search the NT for other instances of that sentence type.

Click the Speech Act label, then select “search this resource” on the left to search the NT for other instances of that type of speech act.

Look at the searches you just generated. They’ll look something like this:

{Section <Sentence ~ Interrogative>}

{Section <SpeechAct = Info.:Assert.>}

Now just copy and paste one of them next to the other, and type “INTERSECTS” between them:

{Section <Sentence ~ Interrogative>} INTERSECTS {Section <SpeechAct = Info.:Assert.>}

If you’d like to run this search yourself, and if you have Logos, click here. Run this search, and you’ll see every place in the NT where an interrogative sentence is used as an informative speech act. In other words, what you will find are rhetorical questions.

You can’t find them any other way besides searching with Logos—or taking a highlighter to the Bible yourself. That’s not necessarily a bad idea, but Logos is quicker.