Often when reading the birth narrative of the Christmas story, we filter what the Bible says through our twenty-first-century Western mindset. Combined with images from church nativity plays, holiday cards, and Christmas movies, we’re left with a perspective that’s sometimes not quite accurate.

That’s why considering the culture and context of first-century Israel—as well as the geography of the land—is so important.

***

Luke 2:8 provides some clues that help us understand the geographical setting of the visit of the shepherds at Jesus’ birth and the time of year of Jesus’ birth:

And there were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over their flocks at night. (NIV, emphasis added)

“Nearby” suggests that the shepherds were in Bethlehem’s economic zone, the area that stretched mainly eastward into the Beit Sahour basin, a region dotted with grain fields although bordering the open Judean Wilderness.

‘Living out in the fields’

That the shepherds who visited Mary, Joseph, and Jesus were “living out in the fields” suggests several things.

First, the shepherds must have had rights to be in fields that otherwise would have been sown with grain. Likely they were shepherds connected to the village of Bethlehem, like David (1 Sam 16:11; 17:15, 20; Ps 78:70–71), rather than shepherds of the semi-nomadic variety (i.e., Bedouin). If so, they likely would have known everyone in Bethlehem and been familiar with the community.

Second, the shepherds must have been in the fields at a time when the fields were fallow—that is, after harvest and before plowing and planting. Theirs is a symbiotic relationship: sheep and goats (flocks are nearly always mixed) graze on the stubble of the harvested wheat and barley fields and in the process fertilize the field for the next cycle of plowing and planting.

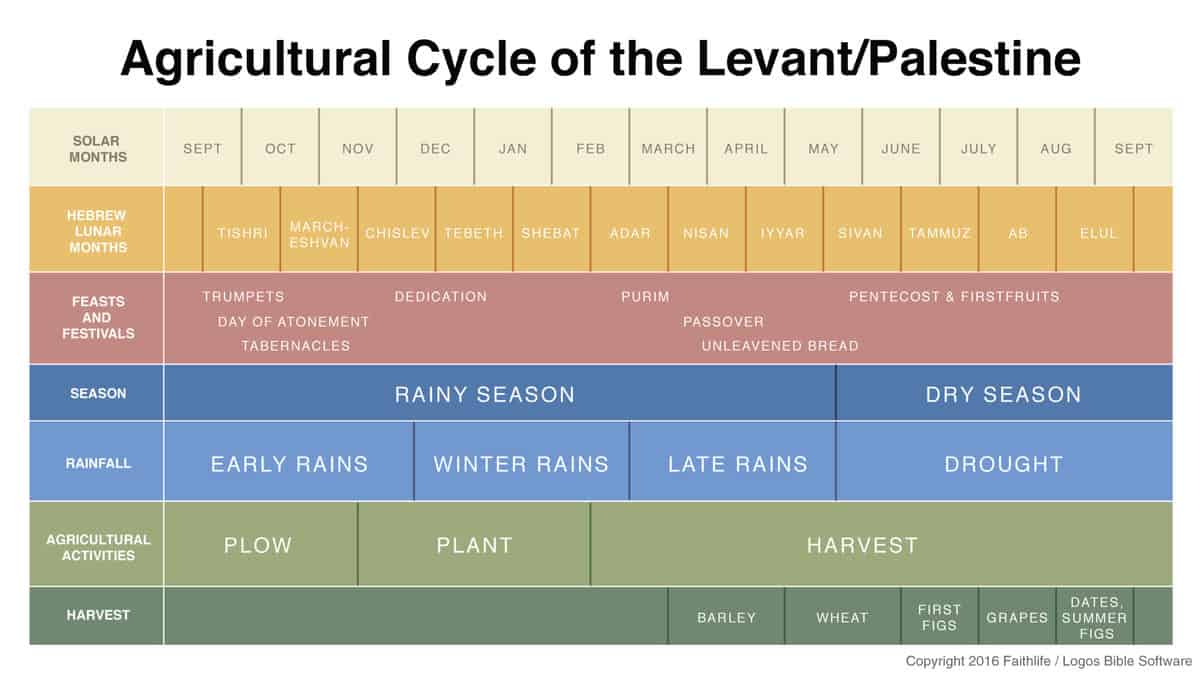

While not negating the age-old tension between farmers and shepherds over land use, within the confines of a village, their relationship is mutually dependent and usually beneficial. Based on the weather patterns of Israel, the season between harvest and plowing is summer through early autumn (June/July through September/October). Fields are plowed at the beginning of the rainy season, and grain (barley and wheat) is planted in November. Barley ripens by March/April (the time of Passover; Exod 23:15; Deut 16:1–8) and wheat a few weeks later in May/early June (the time of Shavuot/Weeks/Pentecost; Exod 23:16; Deut 16:9–12).

Here we can place the story of Ruth, a Bethlehem harvest story (Ruth 2:1–3:18). In late December and January, when the rain is the heaviest, the grain is just beginning to sprout, its tender shoots promising a good harvest as long as shepherds keep their flocks out of the fields. If the rains are good, there is sufficient rainfall, meanwhile, for a thin covering of wild grasses to sprout in the Judean Wilderness and runoff rainfall to collect in wilderness depressions and pools.

The shepherds’ fields

It is here where shepherds drive their flocks when the fields nearer Bethlehem are otherwise sprouting grain. As the rain tapers off in the spring and temperatures rise, the grasses of the wilderness burn off, and the shepherds bring their flocks back up into the hills, entering the fields after the wheat has been harvested in early summer.

These seasonal patterns imply the birth of Jesus was a summertime event Luke’s statement that the shepherds were keeping watch over their flocks “at night” suggests the same. In the rainy wintertime, nighttime temperatures in Bethlehem are typically in the low 50s (degrees Fahrenheit) at best, and can drop below freezing. This is the time of year that flocks would either be deep in the warmer wilderness, or if in Bethlehem, housed in stables, out of the cold and driving rain. In the summertime, temperatures in Bethlehem often rise to the high 80s and 90s (degrees Fahrenheit), hot enough to drive shepherds and flocks into shade and inactivity during the heat of the day. But summer nights out of doors are quite pleasant, a time when shepherding at night would be expected.

Rabbinic sources (m. Shekalim 7:4) indicate that certain fields at Migdal Eder (lit. “watchtower of the flock;” compare Gen 35:19–21) southeast of Bethlehem were reserved year-round as places where animals that were intended for temple sacrifice were raised. Such shepherds were, it is often supposed, more ritually clean than common shepherds and hence more fitting to be the ones chosen by the angels to visit the infant Jesus.

Shepherds at Jesus’ birth

John the Baptist called Jesus “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29 NIV), and while it may be theologically tempting to associate his birth with shepherds who were already connected to the ritual of temple sacrifice, this can in no way be proven.1

***

Related articles

- Star of Bethlehem: Magi, Astrology, and Epiphany

- 3 Reasons to Study the Biblical Geography of Israel

- What Biblical Archaeology and Geography Teach Us

- What the Tyrant King Herod Taught Me about Advent

- Wright, Paul H. 2016. “The Birthplace of Jesus and the Journeys of His First Visitors.” In Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Gospels, edited by Barry J. Beitzel and Kristopher A. Lyle (Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA, 2016), 5–6.