American Christianity is, in many ways, a cultural and denominational hodgepodge. Colonization led to certain emphases among American Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Baptists. And as Pentecostalism, Methodism, and others were added to the American landscape, the range of religious possibilities increased all the more.

Parallel to the history of these theological traditions, however, is a history of race. In order to understand the phenomenon that we often refer to as the Black or the African-American church, it is important to understand the role of race in American society.

Apart from understanding that history, one will not be able to make sense of the Black church.

Table of contents

The early racial context of the Black church

Although the concept of race is not a Black–white binary, it was originally mobilized along those lines. Far from being natural categories, European colonizers formed the concepts of whiteness and Blackness in order to justify racialized chattel slavery.

They were motivated by greed. When the Portuguese encountered slavery during their African voyages, their first thought was not, “These people are darker-skinned”; rather, “We need labor to expand our markets. Slavery would be an incredibly cheap way to do that!” The spice, silk, and cotton trades that built the early American economy were upheld by economic exploitation, fueled and justified by the category of race.

The Black church was born out of this context: a world shaped to exploit and dominate Black people. In the midst of that adversity and persecution at the hands of those claiming to be Christian themselves, enslaved Africans came into contact with the Word of God and were changed by it.

Despite the ways enslavers cherry-picked and distorted the Scriptures to justify racialized slavery, Black people encountered the Word and in it discovered the God who sought to set them free.

When facing the violence and injustice of American slavery, Black people found a number of avenues of resistance. But the Bible provided them their most powerful weapon. Many Black people found a narrative theology in Christianity that made sense of their lives and offered them hope for liberation, both in this life and in the life to come.

Since Blackness itself is an imposed category, the primary thing that bound Black churches together was what they resisted: racism. As long as racism exists, historically Black churches will continue to bear witness to the fact that Christianity properly understood must not tolerate injustice. The seeds of the first Black denomination were sown in this soil.

The early religious context of the Black church

Racialized chattel slavery was an all-encompassing institution. Not only did enslavers control the labor of the enslaved, but they attempted to control every element of their lives.

In 1705, Virginia enacted a law stating that “the baptism of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage; and that all children shall be bond or free, according to the condition of their mothers.” This law was much more disturbing than is immediately apparent.

In the first half, the state of Virginia wanted to deny any assumption that spiritual and material realities had any substantive link to one another. Some of the enslaved astutely noticed that the Scriptures provided ample data to condemn the egregious sin of American slavery. When Christ said, “If the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed” (John 8:36), they took his words to apply both spiritually and materially. Virginia, however, knew that if mass conversion led to mass emancipation, its economy and influence would suffer severely. So the state declared baptism irrelevant to one’s condition of enslavement.

The second half of the law hinted at the sexual exploitation central to American slavery: the children of enslaved women were also to be enslaved. Many white enslavers fathered children by enslaved women whom they exploited. This law, in essence, increased their wealth and labor force as a result. This was the milieu in which enslaved Africans made their lives.

When the enslaved became Christians, they were often required by law to have white ministers and supervision, since enslavers feared that slaves’ newfound Christian beliefs could foment rebellion. Nat Turner’s insurrection traumatically shaped the memories of white enslavers, leading them to erect legal and physical obstacles to Black self-empowerment and self-expression, especially in the South. In the North, where freedom existed, however, Black Christians had the opportunity to create their own institutions.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most Black Christians were either Baptist or Methodist, as those were the most evangelistic denominations. Baptists and Methodists put resources into evangelizing the enslaved while denominations like the Presbyterians were more reticent to do so, fearing it could destabilize a white supremacist status quo.

During the Great Awakening, Baptists and Methodists encouraged free Blacks and the enslaved not only to attend but also to preach in their congregations. Some denominations, however, required rigorous theological education in order to do so. Yet these resources were intentionally kept out of the hands of Afro-Americans.

In the nineteenth century, however, beginning with the establishment of the AME Church, Black Christians began to move out from under oppressive surveillance.

Historically Black denominations

The way they did this was by forming several more prominent Black denominations.

African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME)

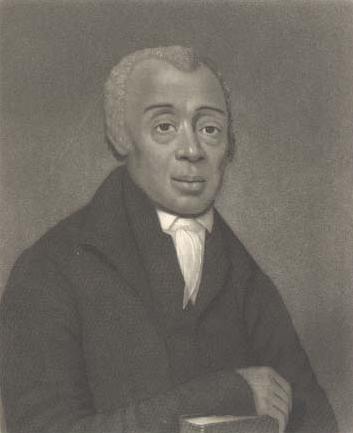

One Sunday morning in 1786, Richard Allen and three of his African-American friends attended St. George’s Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where they usually worshiped. Unaware that Black people were no longer allowed in the seats but were now relegated to stand against the walls, Allen and his friends went into the gallery to take their seats and pray.

As Allen would later recount, one of the trustees approached his friend, Absalom Jones, and physically pulled him up from a position of prayer. Another trustee walked toward William White, another one of Allen’s friends, in order to do the same. Discerning that they were unwelcome, Allen and his friends left that church never to enter again.

Thirty years later in 1816, after ministering outside of predominantly white contexts, Richard Allen gathered five congregations together to form a new denomination: the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), a church with Methodist theology and Episcopalian polity, but with a distinct commitment to battling racial discrimination.

Along with the other predominantly Black denominations, these Black Christians had found themselves in churches that saw them as inferior and restricted their worship. So once they had the opportunity to create their own institutions, they did.

Baptists

Independent Black Baptist churches were present in the country before the Civil War. But the Civil War and emancipation opened the door for more extensive institutional formation. The AME Church and its sister denomination, the AME Zion Church, sent missionaries to the South. And when the formerly enslaved saw the possibility of independence, they took it.

Black Baptists formed their own state conventions. The largest of these, and currently the largest traditionally Black denomination, is the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc., which was formed by a merger of three Black Baptist conventions.

Pentecostals

Around the turn of the twentieth century, another Protestant expression entered the scene: Pentecostalism. The Azusa Street Revival (1906–1916) led by William J. Seymour inspired the founding of the largest Black Pentecostal denomination, the Church of God in Christ (COGIC).

Black diversity

The Black church is not monolithic. Not only are there various historically Black congregations, but the Black community itself is extremely diverse.

What binds each of these denominations together, however, is their history rather than their theology. African-American Christianity runs the full gamut of theological diversity. Nonetheless, the origins of its varied denominations have one thing in common: resistance to racial injustice.

The role of the Black church

The origins of Black churches deeply shaped their roles in Black communities.

Autonomy

First, the existence of Black churches bears witness to the importance of autonomy in Black Christian communities. In a national context where Black Christians were constantly submitted to surveillance, suppression, and suspicion by their White coreligionists, Black Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals, and even Presbyterians (e.g., the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in America) went to the leadership of the churches they attended and asked for resources and permission to start their own communities.

Lamentably, the response was not repentance but merely permission. Given the option between either reshaping their own institutions or amputating their Black membership, predominantly white churches chose the latter. Black Christians, as a result, developed a deep commitment to autonomy.

Justice

The Black church paired this commitment to autonomy with a commitment to their fellow human being. As churches born out of oppression, Black churches maintained a commitment not only to Christ and the Scriptures, but also a commitment to justice and to the Black community.

During Reconstruction and Jim Crow, anti-Black racism became more entrenched and more violent. Churches were the most powerful institutions in Black communities during this period. As such, they naturally became the primary sites of resistance.

Churches served as sites for mutual aid, job training, banking, and education. Pastors and lay Christians would speak out from the Scriptures against racial discrimination, racial violence, convict leasing, and lynching. In the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the AME’s newspaper The Christian Recorder had over one hundred articles and editorials against lynching, offering Christian communities diverse methods of resistance.

This history bears witness to one of the most significant distinctives of the Black church in America: a profound commitment both to people’s spiritual and material well-being. Black Christians have never had the freedom not to develop a theology of political involvement or suffering. In a society and nation that insisted on their inferiority, Black Christians, through their churches and the Scriptures, refused those lies.

Black churches were also central in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Black churches, however, were not unanimous in their involvement, as many saw activists like Martin Luther King Jr. as troublemakers, and some did not financially support the movement.

Nonetheless, King himself was a child of the Black church and a minister within it. At the core of King’s commitment to nonviolent resistance to injustice was his commitment to Christ and the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount. King did not conjure up these commitments out of thin air; rather, he had imbibed them from his youth and upbringing in Black Christian communities.

Black churches imbued their members with a reverence for Christ, a reverence for the Scriptures, and a robust commitment to the common good.

Conclusion

When one considers the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, one finds that Lutheran, Reformed, and Anabaptist churches were distinguished primarily by their theologies. These traditions were largely defined by how far and in what ways they diverged from Roman Catholic orthodoxy on matters like justification, the meaning of baptism and the Eucharist, and the authority of the pope. Denominations splintered largely for theological reasons, although social and economic factors made those splinters more permanent.

The Black church in America, in contrast, was born primarily from social and economic conflict. In this way, the Black church in America and its denominations are quintessentially American. Black Baptists did not leave their White Baptist churches because of theological disagreement. Rather, they left because they experienced restrictions to their worship. They built their own autonomous institutions because the other options presented to them were oppressive.

This reality speaks to the longevity and necessity of historically Black churches. As long as racism has any hold or presence both in the church and the nation, the need remains for Christian communities to bear witness to the kingdom of God by reminding this country that racial oppression and exploitation are contrary to the gospel.

In the United States, Black churches have served as these communities, and likely will continue to do so for years to come.

Related articles

- The Definitive Guide to Christian Denominations

- 6 Black Theologians from Church History You Should Know

- What Is Repentance? A Moving Description by Charles Octavius Boothe

Learn more about the history and distinctives of Black churches

Mobile Ed: CS251 History and Theology of the African American Church (7 hour course)

Regular price: $259.99

The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism

Regular price: $12.99